Late one September night in Atlanta, Killer Mike picked me up from

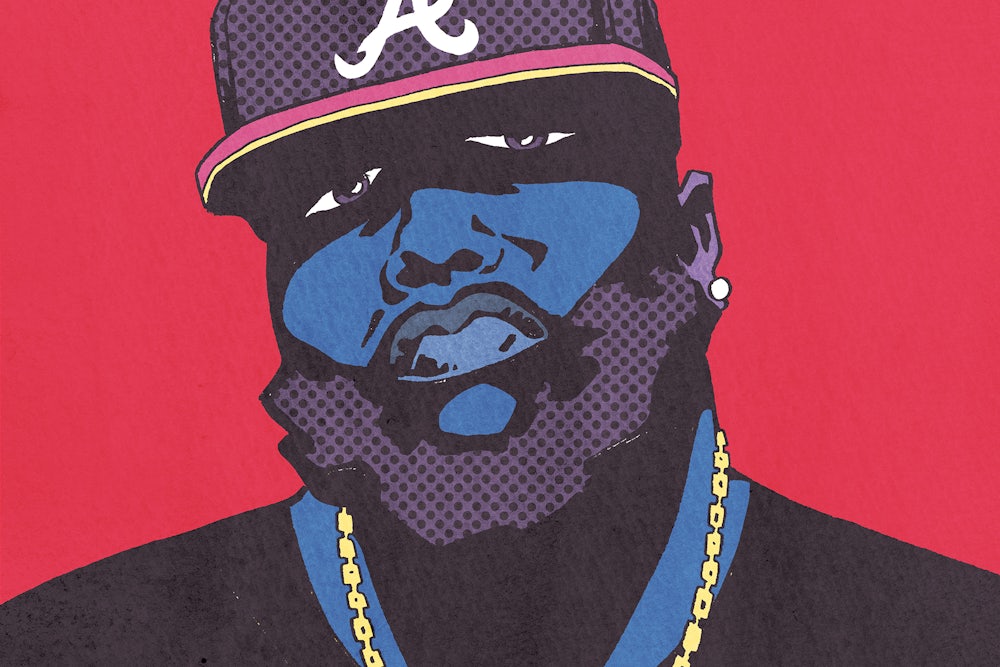

my hotel in a black Chevy Silverado. He’s a heavyset man with a dense beard, a

little over six feet tall, thick and stocky and built like an offensive

lineman. “For all my proclivities for thuggery, I am a typical middle-class

dad,” he said. “I’m a gangsta rap suburban father!”

Killer Mike, whose given name is Michael Render, does lead a decidedly bourgeois life at home. He has four children—two girls and two boys, ages eight to 21—and he co-owns a string of Atlanta barbershops with his wife, Shana (also known as Shay Bigga). But he also told me that he carries “a blade and a firearm” at all times, and later that night, when we stopped in at a strip club, he pulled what looked like a pound of weed out of a backpack, broke it in two, and stuffed half into his shorts. Thug life.

Killer Mike took me on an unhurried drive around west Atlanta, a formerly rough section of the city now in the throes of gentrification. He talked as he drove, about the city’s history, and race. “Atlanta is unique to me,” he said. “You got poor black people, but I also saw this: I saw black doctors, lawyers, educators. All you gotta do is want to be it to see it, and once you see something it can be a reality.”

In Atlanta, the local government is black, the business owners are

black, the students are black, the rich are black. It’s jarring, because in my

experience there’s no place like it in the United States, this concentration of

African American influence. Blackness permeates the city—which means that race

does and doesn’t matter, by which I mean to say I felt a sense of peace there.

“There’s an agreement to figure shit out before you go to Defcon 4,” Killer

Mike said of the city’s police.

On the night of November 24, 2014, Killer Mike was at the Ready Room, a concert hall in central St. Louis, getting ready to perform with El-P, or Jaime Meline, the white rapper who makes up the other half of the critically acclaimed rap duo Run the Jewels. Earlier that evening, a grand jury in Ferguson, Missouri, announced it had declined to indict Darren Wilson, the police officer who shot and killed Michael Brown. Killer Mike addressed the decision from the stage:

I got kicked on my ass when I listened to that prosecutor. You motherfuckers got me today, I knew it was coming … when Eric Holder decided to resign. … You motherfuckers got me today. You kicked me on my ass today, because I have a 20-year-old son and a 12-year-old son, and I’m so afraid for them today. … It is not about race, it is not about class, it is not about color. It is about what they killed him for: It is about poverty, it is about greed, and it is about a war machine. It is us against the motherfucking machine.

The show began, and by night’s end, a fan had posted online a video of Killer Mike’s speech; it went viral. Pitchfork, Spin, Mother Jones, Deadspin, Slate, and The Huffington Post all covered his remarks, as did a wide array of rap blogs and web sites. The New York Times framed Killer Mike as an example of African American rappers distancing themselves from Jay Z-esque financial boasts in favor of “laying bare their innermost struggles.” The Times compared Killer Mike to Kanye West, who in 2005 famously reacted to the Hurricane Katrina tragedy by saying George W. Bush didn’t care about black people.

Killer Mike, 40, was not an unknown figure in the rap world. He

had been performing, on his own and in different groups, since he was a

teenager. His father was a police officer and his mother a florist until “she

got into selling a little coke on the side,” as Killer Mike put it to the Portland

Mercury, and he got his start as a member of an Atlanta rap group called

the Slumlordz. After a yearlong stint at Morehouse College, where he studied

religion and philosophy before dropping out, Killer Mike focused on the group.

He got his first big break in 1994, when he befriended Big Boi, from the rap

group Outkast. After signing with Outkast’s record imprint, Aquemini, in 2000,

Killer Mike appeared on Outkast’s Grammy-winning album, Stankonia, and

Speakerboxxx/ The Love Below, the group’s 2003 genre-changing hit.

Killer Mike’s work has always, at least in part, taken on political themes. (It is also fun. And funny. Killer Mike does dick jokes better than almost anyone, and in October, Run the Jewels released Meow the Jewels, a rerecording of their second album, Run the Jewels 2, made entirely with cat noises. Proceeds from the album will go to a foundation to benefit families who have lost members to police violence.) His first two solo albums, Monster (2003) and I Pledge Allegiance to the Grind (2006), addressed police brutality, particularly the killing of Sean Bell, who was shot by police at his bachelor party in Queens, New York. Yet few people would have called Killer Mike a “political rapper” or even a particularly socially conscious one, even though his songs, playful and strange, often took on current events—on “That’s Life,” from Grind, he raps about how he “dissed Oprah,” lamenting that he never got to “Cruise like Tom through the slums / Where the education’s poor and the children growing dumb.” It’s just that he was a relatively peripheral figure in rap, well-known, perhaps, but certainly not an icon worthy of mention in the same hyped breath as Kanye West.

That changed after St. Louis. People outside of the rap world began to notice that the depth of Killer Mike’s thoughts weren’t limited to rhymes. He wrote op-eds on police brutality and the legitimacy of protest in Baltimore for Billboard. He gave interviews to NPR and PBS, lectured to students at NYU, MIT, and the University of Cincinnati, and made an appearance on Real Time With Bill Maher. (On the show, he called Bill O’Reilly “more full of shit than an outhouse.”) He joined Arianna Huffington as her guest at the White House Correspondents’ Dinner. In one BBC interview, he compared the uprising in Ferguson to the Boston Tea Party: “Riots work,” he said. “I’m an American because of that riot.” Killer Mike had achieved a new level of fame, one reached not because of musical talent so much as a profound willingness to engage with contemporary unrest.

Socially aware rappers have been around as long as there has been

rap, but the impact of artists speaking out on politics and current events

reached its peak in the late 1980s and early 1990s. Rap had by then attracted a

large enough audience that talented and politically astute performers like

Chuck D of Public Enemy, KRS-One (the leader of Boogie Down Productions),

Afrika Bambaataa and the Zulu Nation, KMD, and others realized they’d been

given a new power—to directly address both black and white America—and they

began to use it. In 1991, for example, Public Enemy released “By the Time I Get

to Arizona,” an incendiary song about the state’s refusal to designate Martin

Luther King Jr.’s birthday as a holiday. The state lost an estimated $500

million in revenue to resulting boycotts, according to Arizona tourism

officials. A referendum the following year enacted a holiday honoring King.

Explicitly political rap of this sort was soon eclipsed by the “gangsta” version offered by acts like N.W.A and the Geto Boys, and then the anthemic party raps of Naughty by Nature and the surreal comedy of Biz Markie. In 2006, Nas released Hip Hop Is Dead, which debuted at number one on the U.S. Billboard charts. On the album, he asserted that the commercial success of rap had robbed the music of meaning. “When I say ‘hip-hop is dead,’ basically America is dead,” Nas told MTV. “There is no political voice. Music is dead. … Our way of thinking is dead, our commerce is dead.”

This is a highly abridged and undeniably unfair history, but I think the primary themes are accurate: Politically conscious rap happened; it was meaningful, it was co-opted and commercialized; and then it vanished. Or not really. Yes, there was a period of time during which mainstream rap contained little of what could be considered “political consciousness,” but it’s not like that sort of rap ever really died. You could find it easily enough—Dead Prez, X Clan, Mos Def—on underground and college radio, or mixtapes. Eventually, as circumstances around the country shifted, the political themes returned.

Kanye West’s 2013 album Yeezus was a turning point, with a major star directly choosing to address racism, mass incarceration, private prisons, and the drug war. Then last March, Kendrick Lamar released To Pimp a Butterfly, an unapologetically black album that seemed designed to respond to America’s charged racial climate. Even D’Angelo, the reclusive R&B legend, returned from a 15-year hiatus with Black Messiah: He told The New York Times he had pushed up its release date a year because of the unrest in Ferguson.

Run the Jewels 2 was released on October 24, 2014, two months after Michael Brown was killed. The songs, which speak to mass incarceration, police brutality, foreign war, corruption, religion, and more, are irresistible listening, pulled straight from the deep reservoir of contemporary American racial anxiety. The sound and sensibility is brash and muscular, punk rock wearing a rap suit. “As much as El-P and Killer Mike want to distance themselves from being seen as role models, they are,” Ian Cohen wrote in a breathless Pitchfork review. “Their experience just happens to sound a hell of a lot like the truth.”

The lobby of the W Atlanta Midtown, where we stopped late that first night—before the strip club, after a trip to his studio—is an imposing place, furnished in white marble, and filled with important people, or people who want to seem that way. Killer Mike certainly qualifies: He was here to see and perform with his friend Big Boi at an after-party for Music Midtown, a festival Run the Jewels had played (along with Drake and Elton John). Everyone at the W seemed to recognize Killer Mike. Someone asked to take a selfie with him; another wanted his autograph. Unfortunately, no one had briefed the people at the party check-in desk. An icy blonde working the guest list gave Killer Mike the once-over—long black T-shirt, dark shorts, sneakers—and said he’d have to wait in line.

“I’m Killer Mike,” he said, patiently. “I’m performing.”

That didn’t seem to make any difference. She didn’t know who he was. She only saw a large black man trying to get into an event and it was her job to keep people like him out. She kept asking who he was, and he kept repeating himself, his frustration mounting. Finally, her colleague at the table, an Asian American man, took notice and elbowed the blonde and she let Killer Mike pass. After a few steps, though, he ran into another gatekeeper, a brown-haired white woman, who stuck her elbow out to block his path.

“Don’t ever touch me like that,” he told her, pulling her arm away.

Then, quietly, he delivered a short lecture about celebrities not always looking like how white folks expect them to look. I was stunned. Even here, in Killer Mike’s hometown, among his fans, in a gathering held for the successful and the celebrated, race still mattered. We headed inside.

Grand Hustle Records, the label Killer Mike joined in 2008, sits in a low brick building in an industrial neighborhood, concealed behind a remote-controlled gate. A sign at the entrance reads NO WEAPONS PAST THIS POINT. Two nights after the incident at the W, I went to the studio to watch Killer Mike and El-P cut “Oh My Darling Don’t Cry,” a track from Run the Jewels 2, down to a single, family-friendly minute that Mike told me could be used on The Muppets. (It fell through.) This took some doing. A sample of the original lyrics: “That fuckboy life about to be repealed, that fuckboy shit about to be repelled / Fuckboy jihad, kill infidels, Allahu Akbar BOOM from Mike and El.” It required a few minutes of brow-furrowing concentration before Killer Mike was ready to record. He rapped to himself under his breath to get accustomed to the contours of the song’s new words. (They managed somehow to incorporate parts of Miss Piggy’s song “I’m Sorry” into the mix.) After he finished, we sat down to talk about rap and what Killer Mike thought it could do for the world.

“I just try my best, man, to say something about the shit I see,”

he said. “Because I don’t want to go crazy. I don’t want to be walking around

angry and feeling rage. You say something, and you organize what you can.” In

Killer Mike’s case that means using his recently increased visibility to change

people’s minds. “The way you start to break down systemic racism,” he said, “is

to start building individual relationships with people who are not like you.”

He pointed out that most of the people he meets when he gives university talks

about race are white. “It’s a totally different spiel when I talk at Morehouse,”

he said. “But when I’m talking at MIT? At the University of Cincinnati? I’m

telling white people: In order to stop systemic racism, you must first

befriend, become a colleague of, get to know intimately, put yourself

culturally in the framework of someone who doesn’t look like you,” he said.

“And it sounds so simple. But when you do it, it becomes such a feat. Because

it forces you, on an individual level, to challenge every preconceived thing

your team has ordained as OK.” Systemic racism, he told me, will never end in

this country until “the supposed progressives, or the passively liberal whites

that I speak to at these universities, get angry enough to join forces with the

people who are also fighting the same systems.”

Which means that Killer Mike has learned the same lesson as did

his predecessors in Public Enemy and Boogie Down Productions: His message, like

theirs, has the most force when it is directed at white people. Black folks

already get race. As a sentiment, this should seem obvious, but it

rarely is. Befriending a person of another heritage is a first step: It is

literally the easiest thing you can do. Killer Mike’s real project, then, isn’t

to spout platitudes on racial harmony or to “solve racism.” It is to provoke

empathy, so we have a common foundation—a common language—to build on. These

are baby steps toward justice and equality.

“It’s not enough that we’re angry about Michael Brown,” he said. “There’s a layer beneath race that understands that it is being used as a class structure in this country.” I asked him how he arrived there. “Really, man, it goes back to the commonsense sensibilities of my grandparents,” he added. “They didn’t make me a Buddha, but they just taught me to think. Think.”

And that is Killer Mike’s greatest hope for America: For everyone to wake up and think—about police brutality, about systemic racism, about what it means to be a human being. It doesn’t matter if he’s rapping onstage or rolling blunts in a darkened strip club. He’s been saying this all along. It’s about time we listened.