To put political correctness on college campuses in some actual perspective—terrible scourge, or media hysteria?—it helps to look at another institution that houses and trains a lot of angry and hormonal 18- to 24-year-olds: the U.S. military.

These institutions have more in common than you might think. Both have to make a lot of rules to anticipate the actions of thousands of teens gathered in a strange place with sudden access to freedom and money and booze. Both bring together kids from all over, some of whom haven’t met many people of different races and ethnicities. Their relationships are more intimate than most of us have with our coworkers, because they live together, and they also can’t be immediately fired for being jerks. This is a serious problem for the military, because it needs the teens to kill bad guys, not each other. And so it has procedures for dealing with conflicts over teen identity politics that can be far more intrusive than any university faculty training on microaggressions.

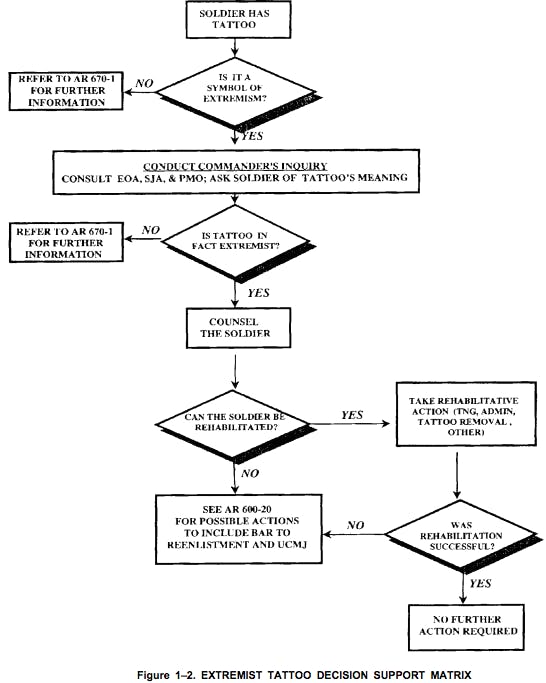

A fascinating example is a chart from a June 2000 Army handbook on the threat of hate groups in the ranks titled, “EXTREMIST TATTOO DECISION SUPPORT MATRIX.” The EXTREMIST TATTOO DECISION SUPPORT MATRIX is about a serious subject, but it is delightfully absurd. Basically all the caution and nervousness in, say, competing university memos about racist Halloween costumes is rendered in the stilted formality of military language and broken down into a multi-step process. The problem the MATRIX is meant to solve is what to do if your soldier appears to have a racist tattoo.

“Private, is that a swastika?” Glances at matrix. “I see. Are you familiar with the connotations of a swastika?” Checks matrix again. “Hmm. And how committed are you to the tenets of national socialism?”

The reason college students have become obsessed with political correctness, according to everyone from National Review to The Atlantic to President Obama, is that kids these days want to be “coddled.” The insinuation is that today’s youth are fragile and weak, the products of “helicopter parenting.” A September Atlantic article stated, with no statistical evidence, that millennials “got a consistent message from adults: life is dangerous, but adults will do everything in their power to protect you from harm.” In a recent interview with ABC News, Obama said:

I do worry if young people start getting trained to think that if somebody says something I don’t like, if somebody says something that hurts my feelings that my only recourse is to shut them up, avoid them, push them away, call on a higher power to protect me from that.

Further, Obama said, his own daughter would be too tough to let some rude comments offend her: “I trust Malia in an argument. If a knucklehead on a college campus starts talking about her, I guarantee you she will give as good as she gets.”

Well, it turns out that even the most macho youth, the people who sign up to fight in wars, don’t want to be the butt of racist jokes. And when they are, they turn to an authority to make it stop.

An Alaska infantry platoon made national headlines in March when a staff sergeant alleged the unit had a tradition of “Racial Thursdays,” in which once a week soldiers could make all the racist jokes they wanted, consequence-free. Less noticed was an Army Times follow-up a few months later reporting that an Army investigation “refutes” the “Racial Thursdays” allegations. It actually doesn’t quite.

The 23-page investigative report, which I read with names redacted, is a fascinating document. The investigator conducted interviews with 48 soldiers, as well as “a random sample of 53 Soldiers (a minimum of 10 was required from each company within 3-21 IN [infantry regiment])” to see if they had heard of Racial Thursdays. Then another 31 soldiers from the company were interviewed.

The report finds that Racial Thursdays isn’t real, because it wasn’t endorsed by unit leaders, even though soldiers referred to it repeatedly, going back to 2009. An Asian soldier and a Muslim soldier both reported offensive comments from noncommissioned officers, yet the report finds that “there are no systemic issues of racial or other forms of discrimination within” the unit. It suggests Racial Thursdays evolved over the years from a way to get away with racist jokes to a way to stop racist jokes.

Regardless of the day of the week, if a Soldier heard another Soldier make a joke or comment of a racial nature, the Soldier would tell the offending Soldier something like, “it must be Racial Thursday,” or “save that for Racial Thursday.” Many of the enlisted Soldiers involved viewed it as just good-natured joking.

Even so, one soldier was moved to a new unit, away from leaders who’d teased him, and a noncommissioned officer was made to declare he knew racist comments were wrong.

There is a thread that runs through much of the commentary on campus political correctness: Can’t you just take a joke? (About how you’re inferior?) In The Atlantic, Caitlin Flanagan laments that college kids rejected a comedian who sang a novelty song about a “sassy black friend.” Reading the Racial Thursdays report, it seems likely that some soldiers made racial jokes they thought would be no big deal—that Asians are bad drivers is one example—but they were a much bigger deal to the people who were subjected to them all the time. “I try to ignore him but when an E-6 talking to you and you’re an E-3 it’s hard to avoid that,” a soldier said, referring to military rank. It would be a bit more risky for Flanagan to argue that infantrymen also want to be wrapped in a parental cocoon. She might get some mean tweets.

Embedded in the Racial Thursdays report is a rebuttal to Obama’s argument that young people shouldn’t “call on a higher power to protect” them from slurs, and that Malia Obama will easily counter any such abuse.

Obama seems to believe that you can stop harassment with the right comeback. Just one zinger and a sexist will see the error of his ways. But it doesn’t work like that in real life. It takes a long time to build a reputation that you are not to be messed with, and that reputation comes much easier when you have actual power. So, for example, when I was an intern, I got occasional inappropriate comments from older male coworkers with real jobs. Now that I have a real job myself, I don’t hear that so much. Is it because my comebacks are so good? It would be nice to think so. But I think it has a lot more to do with dudes subconsciously hedging their networking bets. No one’s gonna add a sexist on LinkedIn.

A driving question in the Army investigation was whether officers and noncommissioned officers celebrated Racial Thursdays, or knew about it and let it happen. That kind of abuse is worse when it comes from people with power.

In the early 1970s, following a series of violent racial incidents, the military created the Defense Race Relations Institute, which led to its Equal Opportunity program. The Commander’s Equal Opportunity Handbook explains that morale was low, because of poor communications across racial lines, and so combat readiness suffered. A Stars and Stripes story from late last year offers a vivid example of why: A congressional hearing into a 1972 riot on the USS Kitty Hawk concluded that black service members weren’t actually experiencing racism, just “perceiving” it—they were “young blacks, who, because of their sensitivity to real or fancied oppression, often enlist with a chip on their shoulder.”

Eventually the military realized it had to take soldiers’ feelings seriously in order to function. If you’re in combat, you need to feel that you’re seen as an equal, otherwise you won’t be sure someone would die for you.

So now there is literally a “higher power,” as Obama put it, in every unit to deal with, as the Army puts it, “diversity management.” Each unit’s commander appoints an equal opportunity leader, whom soldiers—who are trained with the guns and the pushups and all that—can turn to if they have a complaint about treatment based on their identity. In an April article on the Army’s website, a student in an Army Equal Opportunity Leadership Course said, “There has to be a level of cultural awareness within the military, especially at the leadership level, or you’re not going to be able to lead these Soldiers. ... This role as an EO leader plays a vital part in being able to be that bridge between all those various social classes and backgrounds.” An EOLC instructor explained, “For us as EO advisors and leaders, we train with our hearts.”

The Army handbook sounds a lot like stuff you’d read in a freshman sensitivity course at a liberal arts college: “We, as adults, recognize the male pronoun as a generalization, but unless we stop using it, it is all the children will hear.” It highlights military-specific problematic behavior from white males: “Calling minorities and women by their first names while addressing majority members (males) by their titles or rank.” Under a very long section subtitled “Common Causes of Misunderstandings” is the “Continuing Use of ‘Hot Buttons.’” Here the Army asks leaders to—gasp—think about soldiers’ feelings.

“Hot buttons” will always cause an emotional reaction in those who are offended. Leaders who use such terms are labeled as uncaring or lacking sensitivity for their soldiers. ... A soldier who hears the hot buttons might take them out of context, fail to hear the complete message, and take offense when none was intended.

The Army even asks leaders to care when soldiers are offended for no good reason, saying they should be careful with metaphors “even when the expressions originally had nothing to do with race, for example ‘blackballed,’ or ‘white lie,’ or ‘white wash.’” (It’s almost as if this passage was informed by Philip Roth’s The Human Stain.)

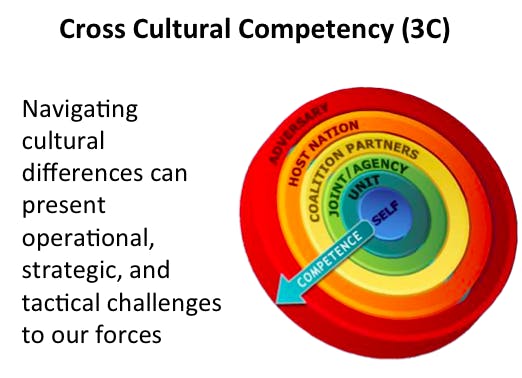

While caring about “feelings” strikes some as frivolous in a university setting, it seems, the Army thinks it’s mission critical. Here’s another cool chart demonstrating just that, from a PowerPoint on cultural awareness from the Defense Equal Opportunity Management Institute. The thrust of it: Understanding cultural differences helps you win wars.

The complaint that kids these days are too soft is an eternal one. A letter to Town and Country magazine in 1771, noted by Mental Floss, complains, “a race of effeminate, self-admiring, emaciated fribbles can never have descended in a direct line from the heroes of Potiers and Agincourt ...” So forget false nostalgia for the days when the youth were stronger and tougher. For institutions built of a foundation of a constant churn of teenagers, managing their relationships is just a matter of practicality.

Several years ago I went to a Halloween party at a German college student group house with a bunch of Army guys. One of the soldiers, a tall, slim, pale guy with fine cheekbones, decided to go dressed as “a black guy.” He covered his face in makeup that made his skin a caramel shade, and put on a medium-length afro wig. When the Americans arrived, we were greeted by a group of Germans, and among them was a tall, thin, light-skinned black guy with fine cheekbones and a medium-length afro. He looked just like the guy who was dressed as a black guy. “Are you dressed as me?” the German guy asked.

It was, oh, a little awkward, but the German guy made the best of it, eventually putting on some white face paint and saying the Army guy was his costume. But the Army guy didn’t quite get it. I told him, “Maybe you should say you’re a specific black guy,” and he laughed. I continued softly, “So you look less racist.” And he looked at me with sincere shock and hurt. Not anger or denial, but like he genuinely hadn’t considered that the costume was offensive, and like I hurt his feelings by suggesting he had bad motives. Some kids really do need to be told the most basic stuff. It’s not political correctness. It’s just good manners.