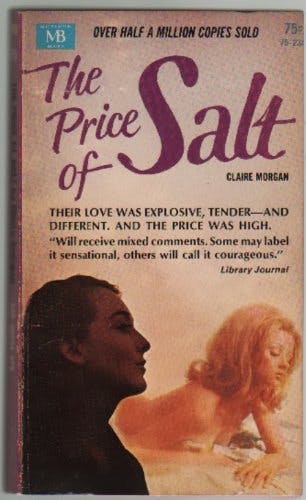

When The Price of Salt was first published in paperback in 1953, Patricia Highsmith was flooded with thousands of letters from readers. The letters came addressed to the author “Claire Morgan,” the pseudonym Highsmith had used for the book, for fear of being labelled what she later called a “lesbian-book writer.” They arrived in the hundreds from male and female readers alike, thanking Highsmith for writing a book that finally showed a same-sex relationship that didn’t end in tragedy.

“Many of the letters that came to me carried such messages as ‘Yours is the first book like this with a happy ending!’” Highsmith wrote years later in a postscript. Other letters asked her for guidance: “I am eighteen and I live in a small town. I feel lonely because I can’t talk to anyone…”

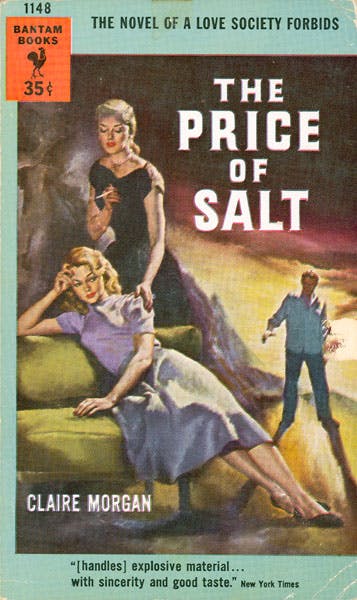

The Price of Salt was a landmark book for queer America, offering readers a powerful and hopeful ending, one that didn’t see the two women at the center of the story end their affair, commit suicide, or attempt murder. But for most of its existence, the novel—which has been adapted into Carol, a new film by Todd Haynes—was overlooked by critics and left out of the canon of twentieth-century queer novels. Highsmith’s publishers rejected it. It eventually found success in a dime-store paperback version, brandished with the catchline “The novel of a love society forbids.”

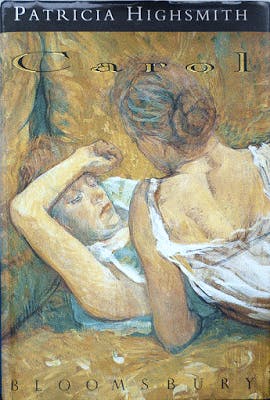

Highsmith did not set out to write a groundbreaking work of lesbian culture. In the brief and unsentimental afterword she contributed to the novel’s 1989 re-issue, published as Carol, it’s clear she wanted to place more emphasis on the book’s craft than its queer content. She was inspired to write the book while working in the toy section of a New York department store, a time when she was “vaguely depressed and also short of money.” One morning, a tall blond woman entered her section and, after choosing a doll that Highsmith showed her for a Christmas present, signed a delivery docket and paid, asking that the doll be delivered to her house.

Highsmith decided to augment this fleeting, and mostly unremarkable, encounter into a story of a young woman’s romance with an older housewife, amplifying the emotional intensity she felt for this beautiful stranger into a novel of forbidden romance. After a bout of adult chicken pox, Highsmith feverishly plotted the story of The Price of Salt, mapping a cross-country road trip between the two women as their intense attraction is realized in highway hotel rooms and long car drives on deserted back roads.

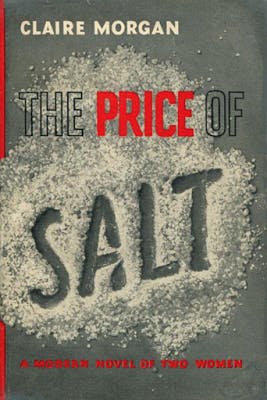

Highsmith, who had been working in a department store while submitting mystery stories to digest-size magazines, decided to publish the novel under a pseudonym, hoping to avoid readers mining the plot for hints of her own personal life. Publishing as Claire Morgan, she wanted to see how readers would respond to the book without the author’s sexuality and status filtering their view. Highsmith sent the manuscript to the publishers of Strangers on the Train, her recent potboiler that was being adapted into a film by Alfred Hitchcock. They rejected the novel. Another publisher released the novel in hardcover in 1952, and a pulp paperback quickly followed.

As a 25-cent paperback with a lurid cover, The Price of Salt entered a growing market. A wave of lesbian pulp novels had first begun being published in the early 1950s, notably Women’s Barracks (1950) and Spring Fire (1952), both of which sold more of than a million copies each. Although these paperbacks were marketed as a cheap and tawdry form of entertainment, they offered many women solace and comfort in the knowledge that they were not the only ones struggling with their sexual identity. As an act of secretive reading, the lesbian pulp novel formed an invisible lesbian community.

While The Price of Salt was a paperback bestseller across the country, it also represented an important axis—some might say fracturing—in the pre-existing trajectory of queer literature. So many novels of this era—a time engulfed in intense homophobia and a culture of paranoia and surveillance, thanks to a pervasive atmosphere of McCarthyism—presented homosexuality as a “lifestyle” that often lead to intense loneliness or disastrous and deathly ends. Highsmith avoided this cliché: The two queer women in The Price of Salt are presented as mentally sound, socially integrated, and don’t have an obsession with suicide or self-harm.

To compare The Price of Salt to Spring Fire, another bestselling lesbian-themed paperback published the same year, is to see how much The Price of Salt broke the mould. In Spring Fire we learn of the romance between an impressionable college freshman and an older but troubled sorority sister. By the denouement, the troubled sorority sister—the one who initiated the lesbian relationship—has had a complete nervous breakdown and had been institutionalised.

Instead, The Price of Salt depicted the more quotidian parts of lesbian life. The novel’s beginning, an everyday encounter with a woman in a department store, is emblematic of the way gay men and women negotiated—“cruised”—public spaces in 1950s. Whether it was the longer than usual stare from the department store counter clerk, or the friendly invitation to meet for a drink one night after work, The Price of Salt detailed the ways lesbians found each other in an intensely homophobic milieu.

Other classic novels of “gay America,” including Gore Vidal’s The City and the Pillar (1948) and Christopher Isherwood’s A Single Man (1964), show gay men struggling to reconcile their sexual identity with their social climate, and unable to form meaningful bonds with other men. Vidal’s infamous book The City and the Pillar was written only a few years before Highsmith wrote The Price of Salt. At the end of Vidal’s story, the male protagonist Jim is raped by his former. (This is the ending in the revised edition; in the originally published version, Jim—the homosexual protagonist—murders his former lover.)

But because The Price of Salt joined the drugstore shelves of lesbian pulp novels at the time, its literary significance was overshadowed by the provocative and public gay male writers of the time, like Vidal and Tennessee Williams. And because an unknown writer authored the book, the merit and success of The Price of Salt could not be tied to Highsmith herself, thereby relegating the novel to its unfortunate 40-year obscurity. Thankfully, The Price of Salt is now enjoying a renewed interest and increasing critical reassessment. (In an essay in this magazine, Terry Castle argued that the transgressive cross-country car chase in the book later inspired Vladimir Nabokov to adopt a similar road trip in Lolita.)

Although it was out of circulation for well over 40 years—no doubt kept in the “adult” section behind front counters of major city libraries—The Price of Salt represents a part of America’s queer history that we should not forget: the unconventional but restorative message that gay identity can not only be successfully found in an age of intense homophobia and suspicion, but that love was also indeed possible.