During my first year at New York’s Fashion Institute of Technology, I made the acquaintance of a cam-girl. Rebecca worked out of a cubicle, mechanically fucking a motorized dildo that the guy on the other side of the monitor thought he controlled. She soon figured out more lucrative arrangements. She introduced me to her clients over a luxurious dinner, but sugar baby-hood wasn’t for me. Filet mignon didn’t taste like much in that company.

Still, her paycheck awed me.

I had only one skill: drawing pictures. But the tools that were required to become a professional artist—a website, a properly printed portfolio, a constant stream of quality supplies—cost more than I could make working retail. Meanwhile, in three hours posing for a webcam, Rebecca made what she could have made in a week at a legit job.

We were young women, at a bad school, studying for a competitive, ill-paying industry. What did we have to interest people besides our looks?

It was money that drove me to the naked girl business. But I also wanted to test myself. I wanted to see if I could work in a field as fraught and stigmatized as sex work, and emerge unscathed. I wanted to burn off childhood.

I combed through Craigslist, looking for a way in. After answering dozens of ads—“Very Open Minded Models to Shoot Erotica 4 Art-Exhibits”; “Highly Discreet”—the artist Cynthia von Buhler hired me to pose as a human statue at a loft party. I painted myself white like Venus, with my breasts out and my hips draped in a white sheet. After a night drinking absinthe with Manhattan’s moneyed bohemia, I took home two hundred and fifty dollars in tips, and swore off honest employment forever.

I got my first regular gigs working as an artist’s model. For ten dollars an hour, I shivered before roomfuls of university students. Poses started at thirty seconds, and by the end, we stayed frozen for twenty minutes at a time. Posing had all the fascination of sitting on a cross-country bus ride with no book. My eyes would blur and my back would scream, and I’d wonder how long time could possibly last, but it lasted longer. The students would not speak to the models directly, ostensibly out of respect, instead addressing me through the teacher. Professionalism meant objectification—not the sexy kind, but the kind that turns you into an object, like a chair.

I modeled for Michael Deas, the artist who’d created the image of the Grecian-robed woman holding a torch in the modern version of the Columbia Pictures logo, and for Will Cotton, the famous painter of cotton candy landscapes. I posed for classes of adult amateurs. If an artist failed to capture my face, I’d tell him. If he yelled at me for moving, I’d flip him off. “If you were any good at anatomy, it wouldn’t matter,” I’d reply.

Inspired by Kiki de Montparnasse’s style, I trawled a Goodwill store for the perfect kimono. I found one in red silk lined with white, embroidered with dragons, with a large rip down one side. When I posed for artists, I’d shuck it off on the stand, as though my body were a revelation.

But ten dollars an hour wasn’t going to change my life, or even buy me basic artist supplies. So I returned to the Internet. Back in the 2000s, girls like me—who were too short, thick, or plain to be fashion models, and not willing to shuck off all respectability by posing in actual porn—could tap into a flourishing semi-underground business posing for amateur photographers. We called these photographers “Guys With Cameras,” or GWCs. They paid a hundred bucks an hour.

For legit photographers—whether in porn or fashion—the point of any shoot was the finished image. For GWCs, the point was the naked girl in their hotel room. We called ourselves models, but we were more like private strippers. Their cameras were the lie they told themselves.

Because we worked on the margins, we Internet models all knew each other, and we extended one another what protection we could. We spread word about who was a good guy and who was a sociopath, knowing full well that the police would do nothing if one of these sessions ended in rape. I knew a girl who had worked as a bondage model. While tied up, the photographer threatened to kill her. She wept. He let her go. When she went to the police, they shrugged her off. Later, the photographer murdered a different model.

The first GWC I posed for was a guy named Stewart. He met me in a coffee shop with what I can only describe as a binder full of naked women. They seemed so vulnerable, these awkward creatures he proudly thought he’d made sexy. The camera flash highlighted their razor burn, their raw red knees. This I could not abide. What I lacked in modesty, I made up for in vanity. My tits could be on the Internet, but not my vulnerability. I took Stewart’s hundred bucks and posed till my muscles wept, convincing him that black-and-white film would make his photos “artistic.”

The first time I took off my clothes for Stewart, I thought the world would end. After a few sessions, I kicked my dress away impatiently, indifferent to my skin.

If I was going to be naked, I didn’t want it to involve unflattering contortions in Stewart’s living room. I took the best of his photos, jacked the contrast on my cracked copy of Photoshop, and put them on a website called One Model Place, which hosted models’ portfolios for ten bucks a month. OMP’s Floridian tackiness and dot-com pretensions came with an insistence that it was used by the fashion industry. It was not.

Within hours of posting my portfolio, my Hotmail started pinging.

I posed for a Hasidic Jewish guy in the Bronx amid hundreds of hard-boiled eggs. I was broke enough to take some home to eat later. I posed for sweet, shy accountants, and for fetish photographers who told me my tits looked like I’d had three kids. Each time, I loved two things: painting my mask in the mirror of a hotel room bathroom, and, three hours later, counting bills in the same bathroom. I was a sleek machine for extracting money. I remained untouched.

One GWC, rich enough that he had original Toulouse-Lautrecs in his living room, spent the whole shoot berating my tits. “The model before you had perfect breasts,” he told me. He was in his sixties, and he looked like a hobbit: squat, hunched, and covered in unexpected hair. I walked by his wife on the way to his studio. Like him, she was petite and elderly, her finger weighed down by a massive diamond. She did not look my way. Before the shoot, the GWC showed me portfolios of his work. Most were photos of himself, crouching over bound models, holding a vibrator between their legs like an eggbeater. He ran each photo through the sharpen filter on Photoshop until the pixels looked like static, convinced it made the photos “edgy.”

I took his five hundred bucks and recommended him to a fellow model. “He’s horrible, I warned her, “but he pays a lot.” He insulted her too. “Your body is hideous,” he told her. “Molly had perfect breasts.”

One night, I worked a launch party for Café Bohême, a coffee-flavored liqueur. The ad firm in charge of the event wanted to recreate some ersatz Paris at the party. They tried to hire artists to paint, but found real artists too unattractive. Instead I posed for actors, who spent the night drawing stick figures that the guests then tried to buy.

The agency’s filmmaker put a camera in my face and asked if I wanted to live in the Paris of Henry Miller and Toulouse-Lautrec. I didn’t bother to tell him the two men lived fifty years apart.

The company paid me two hundred dollars and a bottle of Café Bohême; every sip tasted as sweet as cash. I hid it in the back of the refrigerator, planning to savor it. My roommate came barreling into the kitchen as I shut the refrigerator door. Apropos of nothing, he told me he’d figured out why men hit on me: because they liked ugly girls. “Low self-esteem,” he said, flashing a knowing grin. Once he got back on his feet, he swore, he’d become an investment banker and fuck fashion models. Unlike me, he had goals.

The next morning, I looked for my bottle of Café Bohême. He’d drunk it all.

Once when I was very broke, an old client called me, asking if I’d model for a music video. Our previous gigs had been demanding—in one shoot, I’d spent hours silently screaming in the center of the Times Square subway station before dawn while he filmed me across the tracks.

For the new shoot, the client spelled out the deal: Two hundred dollars to writhe around in a bikini for a heavy metal video. While a grip poured live crickets on my tits.

I swallowed. “Just my tits?”

“Just your tits.”

I hated crickets. But I needed the money.

On the set (actually an empty parking lot), I lay back on the concrete, closed my eyes, and thought of twenty-dollar bills, stacked in a neat pile. That was a quarter of my rent.

The grip poured the crickets right onto my face.

The crew laughed as I screamed.

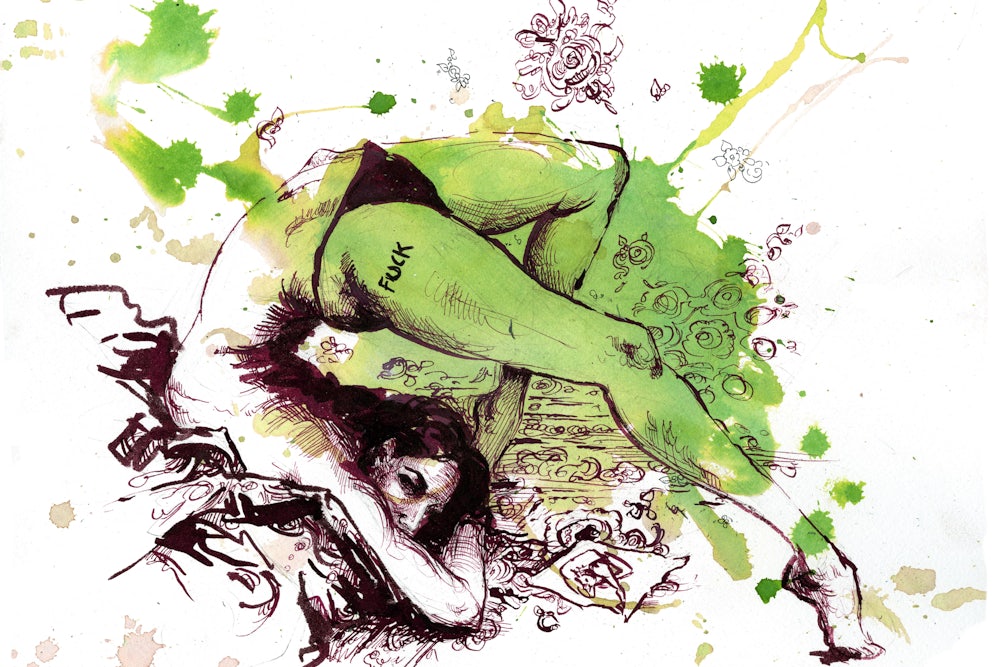

Between shoots, I drew compulsively. I was working on borrowed time—I had a few years when I’d be firm and fresh enough to trade on my looks. By the end of those, I’d better have acquired some longer-lasting trading tokens. I drew pictures of all the glamorous alt models I loved—sea-haired Aprella, angular Darenzia with her half-shaved head. My sketchpads grew fat with portraits of New York’s demimonde. I was obsessed with seeing at the exact moment it most bored me to be seen.

Decades’ worth of underground artists got their start doing covers for Screw magazine: Joe Coleman, Dame Darcy, Spain Rodriguez. Its founder, Al Goldstein, was a legendary bastard: he stalked employees, abused his ex-wife, and once terrorized a former employee by showing up to harass him at his new job—at the New York Times—in a gorilla suit. Such bastardry existed alongside his being a free-speech knight in the Larry Flynt mold, fighting one court case after another, risking imprisonment, and even building a giant middle finger on the lawn of his mansion. By the time I contacted the paper, Goldstein was gone, living in a veterans’ home on Staten Island. He’s dead now, like so many of New York’s saints.

I found a copy at a newspaper stand at Penn Station, ignoring the scandalized vendor while I scribbled down the address. Then I went home and drew some porn.

I sent it in with a letter that read: “No one draws tits like Molly Crabapple.”

A week later, Screw called me. They offered me a cover, for a hundred whole dollars. I thought I’d made it.

“Molly! I got a cartoon into the New Yorker!”

John, my best friend at FIT, phoned me while I was sitting in my mother’s apartment. While I was having crickets poured on my face, John had been sitting in the New Yorker’s offices day after day, drawing cartoons and waiting for the cartoon editor, Bob Mankoff, to reject them. After a year, one of his pieces finally made the cut.

“How much are you getting?” I asked.

“Eight hundred dollars! And they might buy more.”

“That’s wonderful!” I said. I hate you, I thought.

I slammed my laptop shut. Back to work.

This article is excerpted from Drawing Blood by Molly Crabapple, which will be published in December 2015 by Harper Perennial, an imprint of HarperCollins. All rights reserved.