In May 2009, Professor Robyn Warhol traveled from her home in Vermont to Houston, Texas, where she joined her friend and colleague Helena Michie for a dinner party. With thirteen other diners, the two professors of English first prepared and then made their way through eight courses, including beef broth, haddock, steak, mutton, chicken, and chocolate profiteroles. Strictly speaking, they should have topped the chicken with crawfish as well as poached eggs; crawfish not being in season in Texas in May, they used crab claws. The dinner was a recreation of one eaten 132 years earlier, in one of England’s grandest country houses. Among the guests at this first dinner was George Scharf, founding director of the National Portrait Gallery in London, a man not especially famous in his own day and virtually unknown in ours.

Michie and Warhol intended their dinner to be a culmination of the ten years they had spent studying Scharf. They had first encountered him in the course of their research into Victorian food, when they had found an album of his, filled with invitation cards, menus and seating plans for meals he had attended. A ceremonial dinner seemed an appropriate way for the academics to honor him, and their relationship to him. But once the dishes were cleared away, and the blog of the dining experience was complete, Michie and Warhol realized they were not yet done with the person they sometimes referred to, affectionately, as “The Most Boring Man in the World.” The result of their continuing investigations is Love Among the Archives: Writing the Lives of Sir George Scharf, Victorian Bachelor, a not-quite-biography about a not-quite-interesting Victorian.

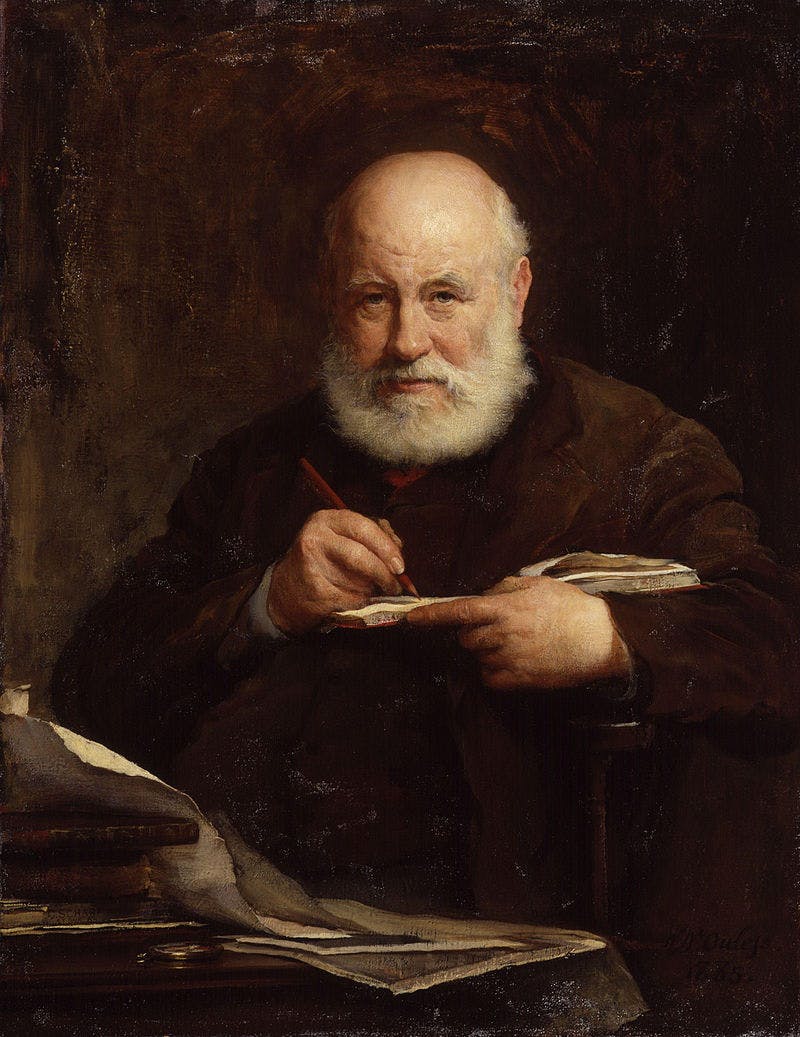

Scharf was born in 1820 to a German artist father, who had arrived in London four years earlier, and a mother who owned a grocery store. Aged nineteen, he traveled to Turkey with Sir Charles Fellows, the archaeologist who excavated more than a dozen ancient cities and brought back some of their finest monuments to the British Museum. Over the next fifteen years, Scharf became a respected authority on art, although for a long time professional success did not bring him financial stability. In 1857, he was appointed secretary and director of the new National Portrait Gallery, a position he held almost until his death, overseeing the Gallery’s development into one of England’s most important collections of art. He also gave advice to royalty and nobility, including Prince Albert, on how to curate and display their art collections. He loved the wealthy and titled, perhaps all the more intensely because of his lower-middle-class upbringing. He loved rich meals, and suffered from the effects of too much eating and drinking. He died in 1895, three months after receiving a knighthood from the Queen.

Before the dinner, Michie and Warhol had been determined not to write a life of George Scharf. The replica dinner party worked so well not just because of Scharf’s love of food but also because of the nature of the plentiful records he left behind. These records, which include diaries, account books and letters, are rich in everyday detail (food consumed, money spent, weather observed) but strikingly poor in those details that combine to produce a compelling biographical narrative: interiority, the subject’s participation in or reflections on historical events, the texture of the subject’s relationships with those around him. In a representative diary entry, describing a dinner party that Scharf himself gave, he lists the names of his guests, draws a seating plan, and then has nothing more to say than “Very lively talk, Extra waiter (Midland). All carving done off the table. The hired flowers & new table linen looked very nice. To bed after 1 o’clock.”

Writing the kind of biography that moves from its subject’s birth to his death, creating him as a psychologically rounded character, wasn’t really a possibility for Michie and Warhol, then. But, as they point out, this approach has seemed old-fashioned for a while, in comparison to more inventive works of recent years, such as the biography of a group of friends (The Fellowship by Philip Zaleski and Carol Zaleski), a life or lives told through a series of objects (Deborah Lutz’s The Bronte Cabinet: Three Lives in Nine Objects) or a single event (The Immortal Dinner by Penelope Hughes-Hallet). But although the approach of these works is experimental, their content often relies as much as birth-to-death biographies on those things conspicuously absent from Scharf’s documents.

Michie and Warhol’s historian friends advised them to overcome the problem of these absences by treating him as a representative of his age rather than as an individual: someone who can tell us about the lives of Victorian bachelors, of 19th-century children of immigrants, of professionals whose rise coincided with the consolidation of a professional class. But Michie and Warhol are literary critics, not historians, and they sought from Scharf what they would seek from a character in a Victorian novel: ideally, psychological development, and if not that, at least a certain particularity. They decided to write a new kind of biography, which they call “somatic life-writing”. Somatic life-writing focuses on the “minutiae of lived experience,” incorporating those things usually considered “too obvious or too trivial to relate.” “We are lowering the threshold of the subnarratable,” they say, somewhat ominously. In doing so, they ask both who George Scharf was and what it felt like to inhabit his body: to experience his peculiar digestive complaints and sensitivities to the weather, to keep enjoying elaborate meals despite those digestive complaints, to rely on his housekeeper’s husband to help him in and out of the bath.

The somatic biography fits into several contemporary trends. Everyday studies and food studies continue to develop as academic disciplines, the first examining the activities of daily life, and the second the cultural and political resonances of what we eat, as well as the experience of producing and consuming food. Michie and Warhol see their dinner party as part of an increasing interest in historical reenactment, both within the academy and without. Such reenactment ranges from World War II video games to the work and life of Sarah A. Chrisman, author of Victorian Secrets and This Victorian Life. Chrisman’s article on Vox about living as much as possible like a (white, middle-class) Victorian caused a flurry in September, with critics queuing up to point out that her version of Victoriana ignores the imperialism, exploitation and sexism that produced many of the 19th-century objects she uses. Meanwhile, Karl Ove Knausgaard’s unflaggingly detailed autobiographical novels show the happy results of lavishing as much description on a bowl of cereal as on a love affair.

Michie and Warhol admit that recreating the physical experience of any Victorian is a very approximate affair. Did Scharf eat every one of the fourteen or fifteen dishes sometimes on offer at a single meal? How big were his portions? Even if we match him mouthful for mouthful, our physical and mental responses will be different. Most twenty-first-century stomachs aren’t used to holding so much from a single sitting. Dishes that Victorians would have regarded as old favorites will seem to us exciting, odd or plain revolting (poultry “boned, stuffed, rolled, poached, coated in aspic and sliced”?). Chrisman washes with a bowl and pitcher and winds a mechanical clock every morning, but she does so with an awareness of the modern alternatives, and of herself as having chosen a lifestyle that, however ordinary it would have been 130 years ago, now separates her from her contemporaries.

Love Among the Archives faces difficulties beyond the impossibility of accurate representation. To eat a reconstruction of a Victorian meal, even to read about such a reconstruction, is delightful and informative. To know that Scharf recorded every shilling he spent is to learn much about both the material world of the striving middle-class Victorian, and the extent of Scharf’s financial anxiety. But to see menu after menu and shilling after shilling, without any larger narrative, produces the kind of tedium that led Michie and Warhol to nickname Scharf the world’s most boring man. Physical existence may be a novel and productive place for a biography to begin, but it cannot be a beginning and an ending. But, in Scharf’s case at least, anything more will rely on considerable amounts of guesswork and imagination.

Michie and Warhol therefore blend somatic life-writing with what they call metabiography: the story of how they started researching Scharf in the first place, and their fantasies and frustrations as they travel between archives, attempting to shape his records into a narrative. Here again they inhabit their roles as critics of Victorian literature, reveling in all the material details familiar from realist fiction of the period, but wanting that detail to settle around a recognizable plot: marriage plot, Bildungsroman, ascent through the class system. Each of the chapters in Love Among the Archives takes one of these plots as its starting point, and shows how Scharf’s life, or at least the record of his life, fails to match up.

Michie and Warhol first try out the marriage plot, dominant narrative of the Victorian novel and something that, they acknowledge, they were eager to find in Scharf’s life. Scharf never married. He lived with his mother and aunt until they died. There are no expressions of sexual or romantic feeling in his papers, towards men or women. His biographers start off by asserting that the absence of sex from his records “brings to the foreground other bodily experiences… we can focus on eating, drinking, walking, physical pain, reactions to heat and cold, sketching and the physicality of writing”.

But their desire for romantic desire gets the better of them, and they begin to comb through his diaries for a love interest. After identifying and dismissing several female candidates, Michie and Warhol conclude that he was gay, and pick out one of his small circle of male friends as the most likely object of his affections. Jack Pattisson, two decades younger than George, was the most regular visitor to the Scharf household, both alone and in the company of others. He appears in the diaries as “faithful Jack”, cheerful and sociable, willing to play card games and word puzzles with Scharf’s mother, and frequently staying the night.

At the end of every year, Scharf wrote in his diary a summary of the previous twelve months, and it is in these entries that he comes closest to anything approaching emotion. On December 31, 1862, he noted that Pattisson was “my equal in cordial spirits”, and two sentences later that “As I wrote [the name] Pattisson the clock struck twelve”. “There is something romantic, maybe even a little obsessive, about George’s noting the coincidence of the act of writing that name and the change to the New Year,” the academics point out. When Jack sends George a note telling him that he is engaged to be married, and George records this in his diary, they see in the brevity of the diary entry the suppression of intense emotion. Many of their conclusions about Scharf are based on this kind of extrapolation, which they call “strong close reading” and others might call wishful thinking. At least they show their workings, and confess to their wish for Scharf to have loved and been loved.

Elsewhere, there isn’t even enough material for them to form a hypothesis. Why did George Scharf arrange to move house with his aunt and his mother without informing his father of their plans, leaving him behind in their old home? Try as they might, Michie and Warhol can’t come up with a convincing explanation for this extraordinary behavior. They admire Scharf’s sketches and his ability to authenticate and curate paintings but, literary critics rather than art historians, they cheerfully sideline this in their eagerness to understand his position in the class system of late 19th-century England. Yes, he regularly visited the country houses of two noblemen—but did he do so as servant, colleague, or close family friend? Michie and Warhol admit that the mysteries here are small, but they feel their unsolveability no less keenly for that smallness. What did Scharf and Lord Sackville say to one another on their many walks in the hops garden?

The biographers rejoice when they come upon a sketch Scharf made of Lady Mary Stanhope in a boat with two female friends. Lady Mary was the daughter of Lord Stanhope, one of the founders of the National Portrait Gallery. Scharf worked closely with Stanhope and often stayed in his house, rearranging his portrait collection and discussing matters relating to the Gallery. In the boat sketch, Lady Mary is reclining, asleep, face tilted upwards. The intimacy of the depiction suggests a relationship closer than that between a young woman and her father’s lower-class colleague. When Michie and Warhol pick out in the curves and folds of her dress the words “with love, GS”, they conclude exultantly that Scharf was a beloved friend of the Stanhope family, valued for his company as well as for his professional expertise. Not long afterwards, they present their findings at a conference of Victorian Studies and one of their friends points out that “with love” might actually read “black lace”, and the “GS” shapes might not be letters at all, but simply curls meant to give a sense of that lace.

Michie and Warhol place this anecdote at the end of Love Among the Archives, in rueful acknowledgement of all that remains unknown. Though they have experienced excitement, joy and even love (for Scharf and for each other) among the archives, they know that the “payoff” of their years of research is “transient and equivocal”, the process of moving from archive to archive one of “evermore reduced expectations”.

While there’s a poignancy to this, theirs is an essentially comic tale, one that, in the hands of different authors, you can imagine forming the basis of a campus novel or a Geoff Dyer-like memoir. Though Michie and Warhol write themselves into Love Among the Archives in a way seldom seen in biographies or works of scholarship—we see them taking breaks for tea and cake, as well as thumbing through the archives—they never quite relax enough to take center-stage. Good scholars to the end, they remain in their subject’s shadow, unwilling to give themselves the particularity and interiority that they long to find in Scharf. Love Among the Archives is a better biography because of this unwillingness, but two half stories only almost make a story.