Every Republican candidates wants a piece of America’s Evangelicals. The largest religious bloc within the Republican base, Evangelicals have shown themselves to be reliable voters and devoted campaigners, earning them the courtship of GOP presidential hopefuls beginning with Ronald Reagan. Evangelical affection has again been in high demand this primary season, with everyone from Donald Trump to Ted Cruz making plays for their loyalty. But while most appeals to Evangelicals focus on their famed fervor for social issues like religious liberty and abortion, Tuesday night's GOP debate exposed, vis-a-vis Ben Carson, a rarely seen aspect of Evangelical concern: godly economics.

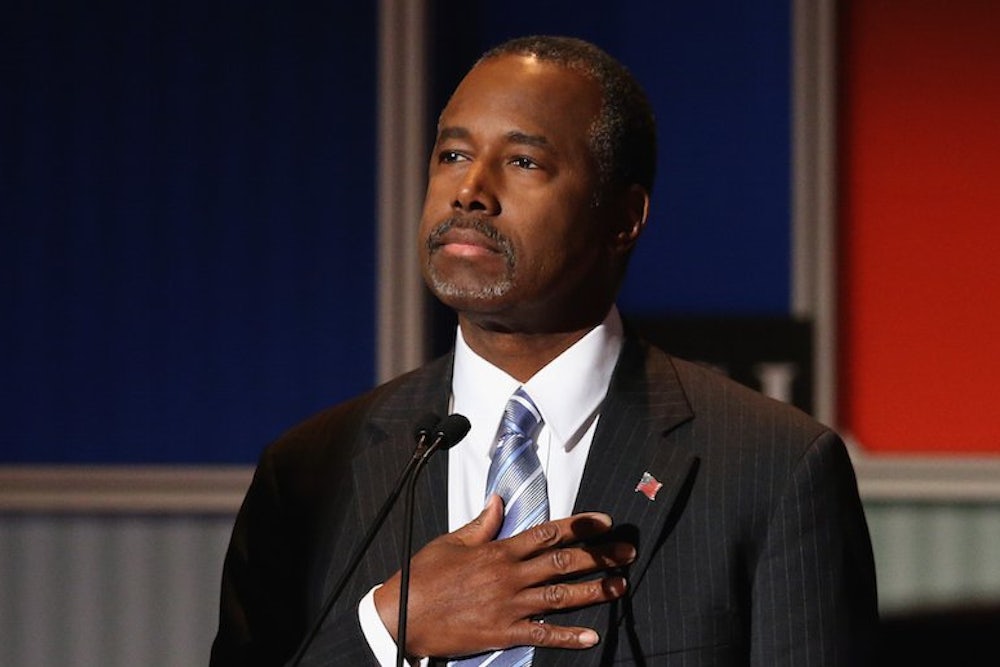

Carson brought up the tragedy of “babies killed by abortionists” in his closing remarks, but for an Evangelical frontrunner, he hewed remarkably close to the debate’s focus on finance and economic policy. Carson’s economic views were markedly different from those of his competitors, however, even those who more or less share a religious background with him, and certainly share his interest in reaching out to Evangelical voters.

“When I talk about tithing, I’m talking about proportionality,” Carson said, elaborating on his flat tax plan. “I don’t see how anything gets a whole lot fairer than that.” He pointed out that his tithe-based tax plan derived its morality not from being identical to Biblical tithes, but from sharing the ideal of fairness Carson views as embodied in the Biblical tithe. In the spirit of that fairness, Carson argued, all tax deductions and loopholes should be eliminated from the tax code, a position that sets him apart even from libertarian Rand Paul, who would still allow for two deductions: the mortgage interest tax deduction and charitable tax deductions.

On the question of charitable deductions, Carson explained that he does value charity, arguing that “if you put more money in people’s pockets, they will actually be more generous rather than less generous.” He went on to emphasize that because he does care about impoverished people, “there will be a rebate for people at the poverty level.” A small ray of mercy, it seems, in an otherwise rigidly flat taxation scheme.

Compared to Paul’s plan, Carson’s proposal might seem like a distinction without a real difference: Both favor closing loopholes and vastly reducing deductions, and setting tax very close to flat. What was different was their reasoning. While Carson emphasized encouraging individual virtues, like charity, and living up to godly standards of fairness, Paul spoke of “government so small you can barely see it.” And for Evangelicals, these differences in language and prioritization matter.

Daniel K. Williams, associate professor of history at the University of West Georgia and author of God’s Own Party: The Making of the Christian Right, has studied Evangelicals for 14 years, with a special focus on the Evangelical political imagination. “Evangelicalism has always emphasized the centrality of individual conversion and an individual’s personal relationship with God,” Williams explained in an email to the New Republic. Thus, “Evangelicals have tended to see economic problems in moralistic and individualistic terms, rather than in terms of impersonal structural problems that can be corrected solely through policy changes.” But while the individualism of Evangelicals might resemble the individualism of right-wingers in general, Williams pointed out that there is a difference. “It’s important to note that [Evangelicals align with Republican economic policies] not because they believe that people are entitled to keep whatever they earn," he said, "but because they believe that individual private citizens, churches, and private charities can do a much more effective job of aiding the poor than the federal government ever can.” While some fiscal conservatives might be fine with individualism extending to unmitigated control over one’s wealth, Evangelicals expect individuals to use their wealth to fulfill their moral obligations.

Which is one reason, Williams explained, that Evangelicals are concerned about inequality. Referring to Vermont senator Bernie Sanders’s visit to Evangelical Liberty University earlier this year, Williams pointed out that “even the conservative leaders at Liberty University who took issue with Sanders said that they shared his moral views about the evils of wealth inequity; they merely had a different view on how best to aid the poor.” Without much of an interest in the structural sources of inequality, it’s easy to see how a genuine Evangelical concern with inequality translates into the kind of "fair" tax plans Carson envisions: While they may not produce egalitarian outcomes in the end, they are at least geared toward treating everyone equitably.

Prior to Tuesday's debate, Carson’s biography rather than his policies seemed to have been the main driver of his Evangelical support. “Many Evangelicals identify with Carson’s rags-to-riches story and his emphasis on hard work, personal conversion, and the help of God as the key to his success,” Williams observed in our exchange. But there was surprisingly little autobiography in Carson’s performance during the debate, aside from a few brief opening remarks. With his showing already being hailed as a success, Carson’s economic outreach to Evangelicals may prove key in setting his campaign apart from his competitors, or perhaps demonstrating the minute differences between Republican economics and Evangelical ones.