What we have to do with here is a very fine mind. Its quality is not in a conventional mold, so it can be mistaken for something else: sensitivity, a liberal and generous spirit, woman's intuition. Mrs. Roosevelt has these, certainly, but she also has what these do not normally imply, a penetrating, powerful and persistent realism. On My Own [the third volume of her autobiography] has much to do with politics and politicians of course - the United Nations, American foreign policy, the Democratic Party, Adlai Stevenson, Tito, Khrushchev. As she talks of such men and matters, one gradually realizes two important things: Mrs. Roosevelt speaks without rhetoric, and she speaks with precision. ... In an age hardly able to think for itself, let alone communicate, except in the cliches of organized power, the resources of such a mind ought to be comprehended.

Mrs. Roosevelt's narrative not only of her experiences but of her tactics during her years in the UN is in effect a formulation of the gyroscopic balance between inflated illusion and narrow gamesmanship, a balance implacably demanded of anyone who really wants to be responsible in the largest affairs of our time. In the course of her telling, she succeeds, amazingly, in making of the methods of the UN - that tediously pedantic object of maddeningly loose hopes -something vital. She knows the difference between action and those imitations of action haunted in the grandiose jargon of our ideology-cursed era: "free world versus slave world," "the principles of freedom," "atheistic Communism," and the like. She simply does not need such rhetoric in order to project her understanding.

As a consequence, Mrs. Roosevelt is the perfect anti-Communist. "I think I should die if I had to live in Soviet Russia," she says, and she knows why. At the same time, she knows that 200 million people do live in Soviet Russia, and 500 million in Red China, and she knows that her reasons for finding Communism deadening are not the reasons several hundred million other people in the world are going to have if - and she knows it is an "if" — they do not give themselves to Communist rule. Mrs. Roosevelt is not bemused by that marvelous egocentricity which imagines that if only the American Way of Life can be "sold" to aspiring millions all will be well. ... [She] recalls to one's mind the tradition of our best liberal leaders, who knew that politics — not even liberal politics — is not fine ideals, but patient application to things as they are. All else is adolescence — fantasy without responsibility.

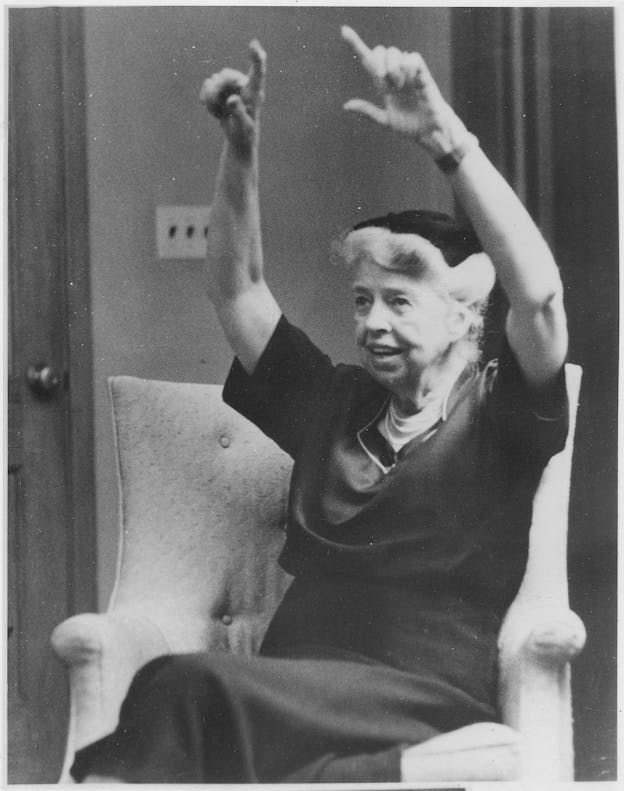

The poise and power of Mrs. Roosevelt's mind are fruits of a long struggle for personal identity. And here, it seems to me, one can find her realism united to her experience as a woman.

It has nothing to do with genes, chromosomes, the "eternal woman" or anything constitutional, but with something social and as old as our civilization: the assumption that heroes of abstract thought should be men, with women left to tend the particular. This may someday be felt to have been a tragic split, for it has helped allow men to pervert the powers of abstract imagination into romantic, fanatic political ideologies, and women, excluded from the glorious affairs of abstract principle, to languish in a few realms where politics has not usually invaded - home, boudoir, Sunday school. Mrs. Roosevelt has not escaped such restrictions by learning the tricks of abstract imagination, by becoming, that is, more like a man. Rather, she has extended her own imagination, shaped by her experiences as a woman, into male domains. Despite every reason in her early life to do so, and despite every reason in her middle life to do so, she never lost her sense of being someone different from the patterns expected of her by others. Her father, her parent-less youth, the patterns of New York "society," mother-in-law, children, stricken husband, governor and President — they all dominated her. "I was lost somewhere deep down inside myself," she said, in This I Remember, quite objectively, without complaint. Nor did she, in the manner of the "emancipated woman," ever rebel. What she did, over years and years, first in New York City, then in New York State, then in the nation, was to find her identity gradually not in some pattern all her own, but precisely in the process of comprehending other people's patterns.

We are all alerted to the falseness of public images. In Mrs. Roosevelt's case, the answer is that there is no answer. Her pattern is to exhibit in herself how the confiict, complexity and passion of other patterns can be accommodated in the reach of a single mind. The result of her long search for herself appears to be that, in the ordinary sense, she has no self. Instead, she is now freely what she always was, a kind of synthesis provided for others. Visiting a primitive Ettu village in Japan, where the people were doomed to "the lowest and most degrading work," she learned, she says, "how important it is to recognize that there is a bond among all peoples." That is what Mrs. Roosevelt's life has been - the recognition of bond.

This is an excerpt of the author's review of Eleanor Roosevelt's On My Own. The full piece was originally published in the New Republic on October 6, 1958.