This week, the Pew Research Center released a major installment of its U.S. Religious Landscape Survey, an ongoing data-gathering effort to measure the religious makeup of the United States. Surveying more than 35,000 adults, Pew found that while the percentage of Americans not identifying with any religion (“nones”) continues to rise, the religiosity of already-religious Americans appears unchanged if not heightened.

Coming at a time of sharpening political divisions over the issue of religion, it would seem the stage is set for the kind of religious versus anti-religious antagonism that gave birth to the New Atheist movement in the early aughts. But in significant ways, New Atheism seems to be on the wane, suggesting a new era of growing conciliation between the two sides.

In 2007, Pew found that 16 percent of Americans identified as unaffiliated with any religion. In its latest study, by contrast, 22.8 percent of adults reported they are religiously unaffiliated. The “nones” are also becoming less spiritual. While Pew wrote in 2007 that it was “simply not accurate to describe this entire group as nonreligious or secular,” roughly two-thirds of today’s nones say religion is unimportant to them, an increase of some 15 million people in seven years. Percentages of unaffiliated adults who do not pray or attend worship services have also risen rapidly since 2007.

But while there are more nones around than before, religious Americans haven’t lessened their spiritual commitments. “Although the share of Americans who identify with a religion has been shrinking, the percentage of religiously affiliated adults who report participation in prayer groups, scripture study groups, or religious education programs is somewhat higher today than it was in 2007 (30 percent vs. 27 percent),” Pew says.

Religious people pray and read scripture at roughly the same rates they reported in 2007, and more religious adults now report sharing their faith with others at least once a week. On the political front, Pew found that Evangelicals, who have been associated with the Republican Party for several decades, are now even more likely to support the GOP than they were in 2007. Nones, meanwhile, tend to lean left politically, forming a larger portion of the Democratic Party than Catholics, mainline Protestants, and Evangelicals, respectively.

The 2007 survey came at the peak of the New Atheist movement. The early to mid-2000s saw the publication of several books by celebrity intellectuals that would form the backbone of the movement, including works by Sam Harris, Richard Dawkins, Daniel Dennett, and Christopher Hitchens. During that time, the New Atheists made numerous appearances (often contentious) on news and talk shows; gave lectures, made films, and held conferences; and made headlines for attacking treasured religious figures, perhaps most notably Mother Teresa. New Atheists were especially incensed by the dominance of the Christian right in America, with sociologists George Yancey and David Williamson arguing in a 2013 book that GOP-centric Christian conservatism had helped shape its own antagonist through its prominent place in American politics. For a time at least, it seemed that tensions between the stridently non-religious and the ardently faithful would only continue to rise.

Which makes today’s relative placidity between the non-religious and religious so remarkable. An example of the truce: Pope Francis has repeatedly asked nonbelievers to send him well wishes in place of prayers during his routine requests that believers pray for him, and the gesture has been well received by atheists, including Harvard's humanist chaplain Greg Epstein. In fact, 68 percent of nones polled in a Pew survey earlier this year took a favorable view of the pontiff, despite their obvious differences in belief. And while religion still frequently occupies national headlines, contemporary debate about belief is more concerned with what spheres religious people should be allowed to exercise their particular convictions, rather than with the factual merits of faith writ large.

But why? After all, the political differences between the faithful and nonreligious have hardly shrunk. So what accounts for the softening of relations between believers and nonbelievers?

Stephen Bullivant, a senior lecturer in theology and ethics at St. Mary’s University at Twickenham and co-author of The Oxford Handbook of Atheism, believes the detente might be a result of intentional efforts on behalf of both sides. “The New Atheists proper... were very important in attracting attention, and galvanizing, that wider constituency,” Bullivant explained in an email to the New Republic, “but even in the early days of [New Atheism] it was quite common to hear atheists (as well as the more broadly 'nonreligious'—most nones aren't actual atheists, of course) express appreciation of Dawkins et al., while being quick to qualify it." For example, they would affirm their atheism, but maintain they had respect for religious people. Bullivant pointed out that many popular atheist texts produced since the rise of the original New Atheists have had a more conciliatory tone, including books by Chris Stedman, Greg Epstein, and Alain de Botton.

“There have also, of course, been moves from the religious side of things too,” Bullivant added. “Popes Benedict and Francis both urged for dialogue between believers and nonbelievers etc., and with the growing numbers of nonreligous, I suspect a lot of churches see nones as people to try and attract (back!) rather than attack.”

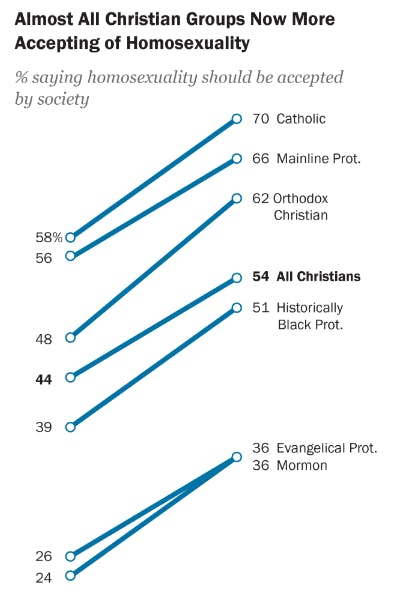

Pew’s own data might provide some explanation as well. While Evangelicals appear to have consolidated somewhat in their support of the GOP, they are nonetheless more accepting of homosexuality now than they were in 2007. Thus while general political differences persist between conservative religious groups like Evangelicals and nonreligious Americans, there may be less intense focus on pushing political action on divisive social issues than there once was. Disagreements still exist, of course, and the occasional conservative Christian still periodically echoes the sentiments of Evangelicals past, but overall public discourse surrounding key issues like gay rights seems to have taken on a less openly hostile tone.

The growing numbers of nones and attendant social acceptability of having no faith has also likely eased pressure on the nonreligious, making their interactions with a still predominantly religious society somewhat less fraught. Richard Cimino, a lecturer in sociology at the University of Richmond who co-authored Atheist Awakening: Secular Activism and Community in America, explained in an email to the New Republic that "the main function of the New Atheism was to raise the consciousness of atheists, give them more confidence so they can 'come out of the closet,' and claim a secular identity." But now that their work is mostly done, secularist attention has turned to building out a nonreligious identity and way of being in society. Still, Bullivant noted, it might be "too soon to speak of a 'post-New Atheism'"—there is still widespread animus surrounding the idea of atheism, especially when it comes to electing candidates to leadership roles.

But with at least one not-particularly-religious candidate faring surprisingly well in the Democratic primaries, that might be changing as well. Whatever the source of relaxed relations between nonreligious and religious Americans, the possibility of cooperation signals a positive development, it seems, for both sides.