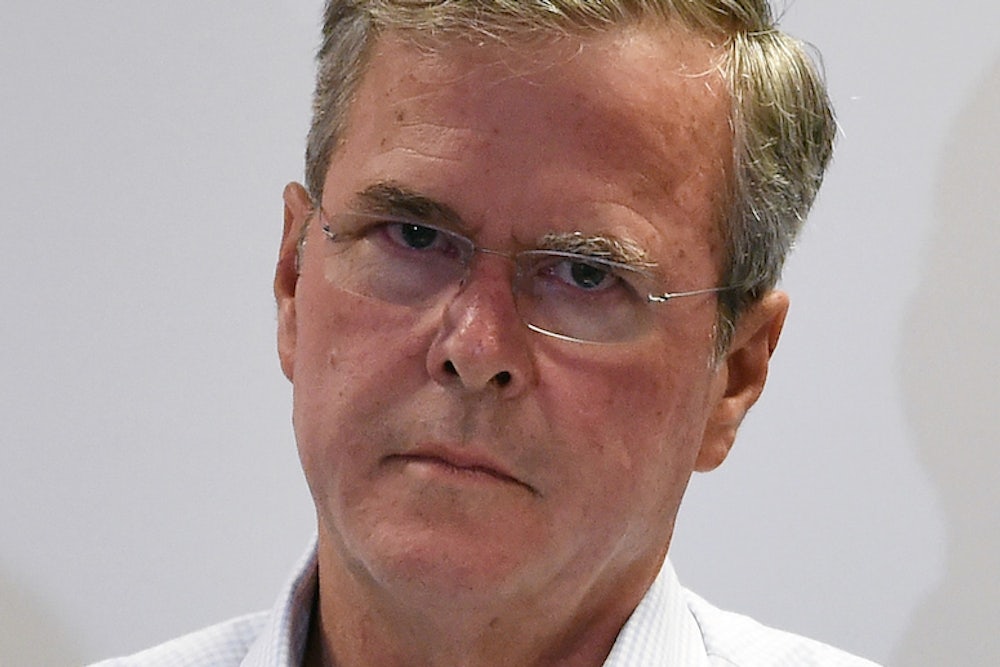

The Jeb Bush campaign has swapped out the language of genuine optimism for the language of forced optimism that often masks hopelessness. Like a pitcher pleading with his impatient manager, or a debtor pleading with a disgruntled bookie, Bush is now pleading to anyone who will listen that he, Jeb, can fix it!

The value of this new slogan is that it responds to everyone by being addressed to no one in particular. Nervous donor worried about your investment in the Bush campaign? Jeb can fix it! Economy not working out for you? Jeb can fix it! Hate Washington? Jeb can fix it!

But the reason Bush finds himself in the doldrums isn’t that he’s back-burnered his claim to competence. It's that nobody particularly cares if the claim true. Conservatives remember Bush’s governorship of Florida fondly. His reputation for competence isn't in question. His problem is that familiar inputs in Republican politics are no longer yielding dependable outcomes.

As Bush ally and former New Hampshire Governor John Sununu told the New York Times recently, “I have no feeling for the electorate anymore. It is not responding the way it used to. Their priorities are so different that if I tried to analyze it I’d be making it up.”

Jeb’s challenge is to fix that—or at least to explain how he'd do it, without widening the rift between him and the Republican electorate. Jeb is promising to fix everything generally, but nothing specifically. What he should do is pledge to fix one big problem in particular: the conservative movement's relationship with the Republican Party.

This is an inherently difficult pitch because it implicates influential conservative activists, whom Republican voters trust more than Republican politicians. But these same voters, presented with evidence of corruption on the part of conservative groups supposedly acting on their behalf, may also be receptive to the idea that Republican politicians and conservative activists are colluding to dupe and fleece them.

The Bush family ironically bears as much responsibility as anyone for corrupting the movement institutions that are now obstructing Jeb’s path to the presidency. Jeb’s own brother, who prototyped the post-modern presidency, gutted sober policy analysis out of conservative politics because it often was detrimental to his ends. But the Bush network is also wide, rich, and knowledgeable enough to recognize how damaging this has become, and, possibly, to change the harmful incentives that control Republicans today.

Bush could run on a promise to clean house where the GOP and the conservative movement intersect. It would be a platform devoted to conservatism, but predicated on the belief that the institutions created to advance conservatism have failed, and that rooting out the rot is a requisite for substantive progress and winning elections.

Among the candidates leading Bush right now are:

- Donald Trump, who has aligned with talk radio hosts willing to vouchsafe fantastical campaign promises for the good of their own ratings.

- Ben Carson, who quite possibly doesn’t realize that his campaign is fleecing Republican voters, because it’s run by people who are hoodwinking him.

- Ted Cruz, who has been amply rewarded by the conservative movement for willfully misleading Republican voters about the fixed Madisonian limits on Republican power in the Obama era.

Together these three candidates enjoy the support of more than half the Republican electorate. That’s a searing indictment of conservative politics today. It also explains, at least in part, why Jeb Bush has been unable to gain traction—even as he succumbed to the same incentives and ran on a fantastical promise to create four percent economic growth in perpetuity.

If time goes on and Bush’s turnaround fails to materialize, his new slogan will become self-undermining. But he can’t actually turn his campaign around unless he correctly identifies the problems that have impeded him so far, and, yes, starts to fix them.