Today’s Paris contains multitudes: Segway-shod tourists cruising docilely to Versailles, children squirming on the streets of the Marais, Minnesotans snapping selfies with the Venus de Milo. There’s glamour, too, and romance; fine art, music, food. But before the photogenic swept streets and trimmed gardens, sometime between the 1700s and the 1920s, Paris was also a city of secrets and filth, of sin and entropy. This is the version of Paris that Luc Sante illuminates in his latest cultural and literary history, The Other Paris: a Paris that predates the whitewashing of urban renewal and institutionalized infrastructure; a city rich with fringe economies, insurrections, micro-societies, and raveled streets; a city that does not—cannot—continue to exist.

The Other Paris is both eulogy and paean to the matrixes of anarchy, creativity, crime, and serendipity that once gave shape to the City of Light. “The past, whatever its drawbacks, was wild,” Sante writes. “By contrast, the present is farmed.” His book is intended to be “a reminder of what life was like in cities when they were as vivid and savage and uncontrollable as they were for many centuries,” and its pages are populated by artists, writers, anarchists, and criminals; the narrative meanders into vignettes and lore. Sante draws primarily from literary, artistic, and cinematic representations, citing novels and poetry, pamphlets, paintings and films alongside more traditional historical accounts. Some of the players will be familiar, even to the non-Francophile—Walter Benjamin, Victor Hugo, Louis Aragon, the Dadas, the Surrealists, and so on—and others, intentionally less so: prostitutes, dissenters, immigrants and rag-pickers, the people whose rage and lust and struggles defined the city they called home.

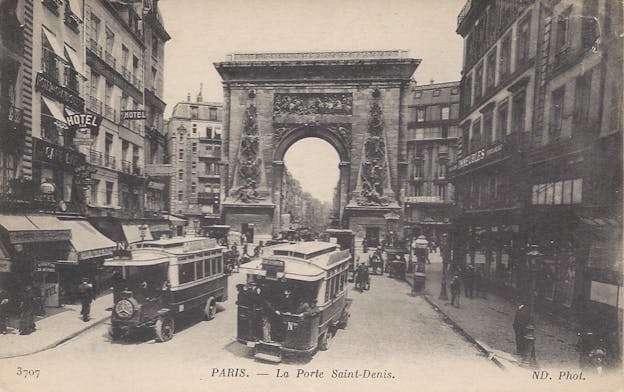

The loss of this Paris began in the mid-nineteenth century, when Napoleon III appointed Baron Haussmann to spearhead a series of public-works projects, intended to transform the city from medieval to modern. Hausmann’s compartmentalized redesign of Paris favored organization, efficiency, commerce, and state control, and the modernization he catalyzed continued into the late 1920s. Neighborhoods were razed, and homogenous, charmless apartment buildings were constructed in their footprints. Sewers were built, parks were planted, and streets were widened. Light was let in. The wild and chaotic underbelly of the city was scattered.

Among the many losses that development in Paris wrought were the disappearances of micro-cities, village-like neighborhoods that managed to sustain themselves just enough for their residents to stay afloat. “There was a flavor to the city that has now been eradicated,” Sante writes. “It had a fugitive lyricism almost impossible to recapture.” A particularly lively example is the community that sprang up in Saint-Jean-de-Latran, a dilapidated cloister in what is now the Latin Quarter. Alexandre Privat d’Anglemont, a journalist and flâneur, documented the odd jobs that people created for themselves: a “zesteuse” who collected discarded lemon rinds and sold the zest to syrup producers; a cleaner who swept jewelers’ floors and sold the gold-dust. These jobs were unconventional, but they were honest—a counterbalance to the preponderance of hustlers, con artists, and thieves.

The Other Paris implicitly criticizes the sanitization of history, and in many ways the book is also an argument against cultural imperialism, gentrification, and the forces of global capitalism. Yet a central dilemma to The Other Paris is just how far to take this argument: while Sante doesn’t glamorize poverty, mourning the loss of Paris’s microeconomies and societal tumult for the color they contribute seems to undercut the experiences of those on the ground. The community at Saint-Jean-de-Latran displayed a mastery of resources, and in hindsight this ingenuity sounds charming. It also sounds fatally hard. Very few—myself included—wish to argue in favor of urban homogeneity. But given the opportunity to decide for themselves, would the Parisian poor have opted out of these self-governed societies, in favor of stability, shelter, economic agency, a sense of peace? Without their voices, it’s impossible to know.

The real hero of The Other Paris is not the vanished poor, but the hyperliterary figure of the flâneur: the stroller, voyeur, and literary walkabout, introduced by Baudelaire and popularized by Walter Benjamin. Sante sees the flâneur as having an ideal relationship with the city, able as one is to “read the entire text of the streets, including its footnotes, interleavings, and marginal commentary,” and “comprehend the city holistically” and “understand it as a living being.” The flâneur is not confined by routine or obligation; he defines his own methods of exploration.

Lovely as the idea is, and much as I believe in the relationship between literature, identity, and sharp observation, I have always been a little wary of the flâneur. While the flâneur-artist may observe and depict a city beautifully, this does not necessarily translate into on-the-ground insight or depth. One cannot be in—and of—every place at once. Besides, flânerie is also a project of escape. Perhaps this is unsympathetic; perhaps to be a flâneur is to sacrifice oneself willingly to the crowd, to deliberately travel the periphery of one’s own lived experience. Yet I cannot help but suspect that the flâneur is motivated not by social concerns, but aesthetic ones. I am irked by the fibers of self-congratulation woven into the acknowledgement of others’ mundane realities.

The flâneur grows increasingly questionable in the context of archives and records, the depictions of a city that long outlast a walk around the perimeter. Narration is power, and the disenfranchised rarely get to appoint their own scribes. The voices in The Other Paris come largely from the outside. This is not a criticism of Sante or his project. It is no fault or failure of his that the Parisian poor lacked a formalized or preserved voice, but it certainly serves as a reminder—and a warning, to anyone interested in the role literature plays in our collective historical archive—of the gaps and disparities that we continue to find in government, business, education, and publishing.

Sante is wholly aware of the erasures, risks, and liberties of artistic representation. He asserts that the stories of Henri Murger—the impoverished writer whose sentimental tales of bohemia inspired Puccini’s La Bohème—are “highfalutin pulp.” Nonetheless, “the myth endures... it will probably last even when the actual fact of bohemia has no remaining living witnesses.” Of Francis Carco’s 1919 novel L’Equipe: Roman des Fortifs, he writes that the Zone—a severely impoverished section of Paris—was “exploited with mythmaking verve.” So too does Sante critically examine the work of Eugène Sue, whose novel The Mysteries of Paris sounds a lot like the crude work of an undergraduate double-majoring in English and Anthropology. Sue was born into wealth but “determined to write the great epic of the people,” and as such immersed himself in the dive bars and dark corners of the Cité. “The result,” Sante writes, “is a sprawling tableau of lower-class Parisian life…with each of the characters embodying some trait, some station, some principle rather than attempting to impersonate individual humans.”

Despite these flaws, Sue became a voice for, if not from, Paris’s poorer citizens. His writing “broke through class barriers and seized the imagination of the whole city… somehow the novel also acted as a genuine agent of social change, inspiring investigative journalism that tallied wages paid to factory workers and compared them with the cost of living—something unheard of until then.” There are, of course, questions of collective imaginations, and who is able to influence them. A representation that spurs people to action may bear positive consequences in the short term. It is more difficult to gauge or evaluate the lasting imprint of a cartoonish and reductive representation on the cultural imagination, and how it will continue to resonate with the collective consciousness.

Urban renewal is a force of erasure. This is the story of Paris, of course, but it’s also the story of London, Singapore, San Francisco, Berlin, Boston, and Prague—among others. Throughout The Other Paris, it becomes increasingly clear that the greatest losses are freedoms: to protest and steal and trick and seduce and hide. When light floods into a neighborhood, surveillance opportunities ride in on its current. Bodies and behaviors are policed. The parameters of what is deemed subversive or radical are defined—and judged, and punished—by outsiders.

The tangible textures that compose a city’s “flavor” may be rendered invisible, but this does not mean that they have disappeared. The aesthetics are different now, but the informal economies of violence and crime and creative methods of survival still exist—even if they are now more difficult to document. The intimate parts of our lives have to a large degree gone virtual: from escort services to underground economies to protests to alternative currencies and modes of connection and abuse. Private lives are no longer drawn, by default, into the streets, and this makes it harder for the city-walker, the flâneur, to glimpse them. The subversive currents of a city continue to flow. They always will. It’s simply that for those in pursuit of a spontaneity, surprise, hazard and creativity—that fugitive lyricism—eye level will no longer suffice.