“When you choose a tattoo, you reveal something about yourself that is already there, even if it’s only a hope.” Thus opens the The World Atlas of Tattoo by Anna Felicity Friedman, eminent tattoo historian and custodian of the excellent scholarly site tattoohistorian.com. This book—part global art historical tome, part coffee-table book of visual wonders—is a valuable corrective to many silly things that we assume about tattooing.

One of those assumptions is that a tattoo is entirely about the person who wears it, rather than their place in time and space and culture. Friedman insists that, while “your tattoo tells me about you and it tells you about yourself,” the tattoo more importantly connects “you to your family, town, and culture.” An atlas is the right format for a book about global tattooing, because “even the most personal tattoo, which seems only to be about your own dreams and ideals, is also about your place in the world.”

Global surveys are very tricky to pull off, because they can feel “ethnology-ish”: white anthropology’s history of distorting its subject according to the expectations and assumptions of the anthropologist and her audience is venerable. In filling a book full of pictures of semi-clothed people (most of whom have had their faces cropped out), Friedman could easily have published a book of clumsy comparativism. When we hold up artefacts from two cultures and ask “what is the same, what different? Are these two things equal?” then we are performing comparativism, and it is a bad way to see things clearly.

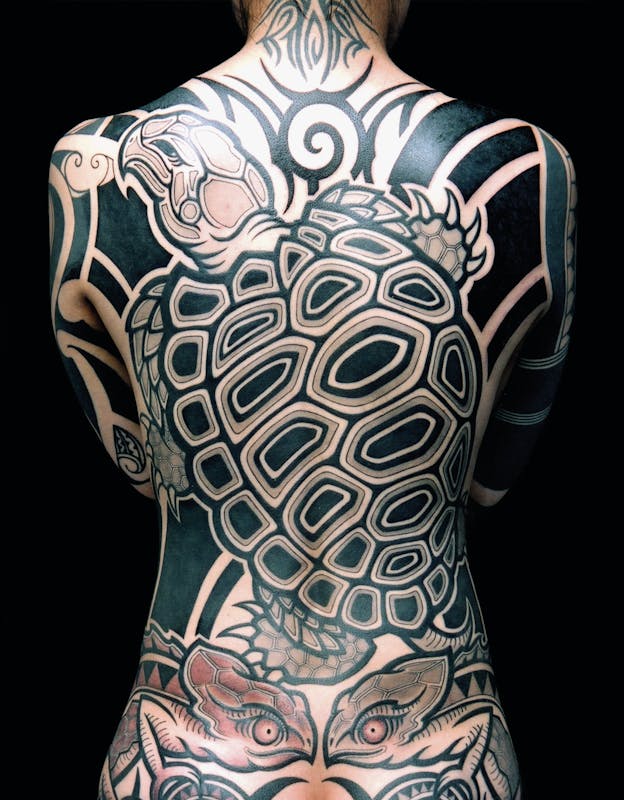

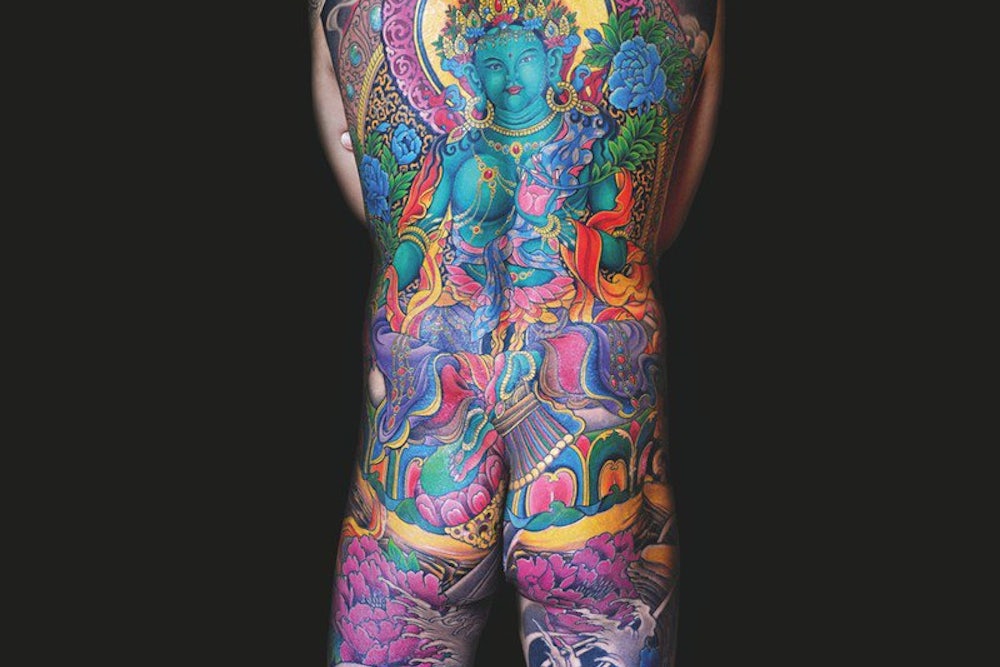

But Friedman has done a great job. The book is divided by region: United States and Canada, Latin America, Europe, Africa and the Middle East (I’m not entirely sure why these aren’t separate), Asia, and Australia and the Oceanic Islands. She has tried hard to “achieve a balance of geographical location, genre, gender, and ethnicity.” With only 100 spots to fill, Friedman can only really gesture to tattoo’s heterogeneity, not survey it, but she has chosen wisely and devoted the vast majority of paper real-estate to photographs of the talents of others. Here are Durga from Yogyakarta, Indonesian new wave expert; dotwork specialist Karolina Czaja from Warsaw; Japanese traditionalist Horimitsu from Tokyo; Portugal’s Nuno Costah, whose tattoos look like illustrations from a children’s book.

There are many surprises here. There is a family by the name of Razzouk in Jerusalem, which has been tattooing Christian pilgrims for hundreds of years. In the late fifties, the Marlboro Man had a hand tattoo. I was also struck by how exceptional Pacific Island tattoo remains, despite the parade of imitations I grew up seeing on Robbie Williams and Mike Tyson. It’s really unmatchable stuff. Admiring the work of Miguel Dark, I wasn’t proud to realize that I walk around the city totally blind to the beauty of Latin American tattoo—the black and grey curlicues of lettering and portraiture is just so much better than I’d ever realized. I had been taking a lot for granted.

At her site, Friedman expresses frustration at myths of white identity like “Western tattooing was previously only the purview of sailors, bikers, criminals, gangs, the lower class,” and myths of white relation to non-white tattooing, like “modern Western tattooing derived from Cook’s voyages to Polynesia.” Her work, this book included, situates the recent uptick of tattooing’s popularity among young North American white people in its place: as one among many cultures of tattoo, not the culture of tattoo.

But this book also counters the idea that there is a watertight distinction between ancient indigenous tradition, practiced by timelessly “native” people, which exists in a different universe to the often derided modern cultures of the prison tatt, the nonsense kanji that actually says “vegetable” or something in Japanese, the stolen symbol, the tramp stamp. Distinctions remain, of course, and appropriation remains a very complicated issue: but all tattoos are contemporary tattoos.

Categorizing tattoo within geographical boundaries is a tricky job, because we live in an artistically globalized world. The chief problem is time. There are deep-time traditions and there are shallower-time traditions, which are difficult to compare. Is the culture of “North American tattoo” the near-extinguished art of the indigenous peoples, or the really quite new “old-school” of hearts, daggers, dancing ladies? The problem is that living tattoos and their style of execution are (literally) indivisibly attached to the people on whom they are tattooed. Tattoos exist on the living, and everybody is living in the present moment. This makes tattoo a singularly postmodern art form, its almost unfathomably ancient traditions mixed up, appropriated, colonized, revived, reviled, beloved, and beautiful upon the skin of the living. Can’t get much more cutting edge than that.