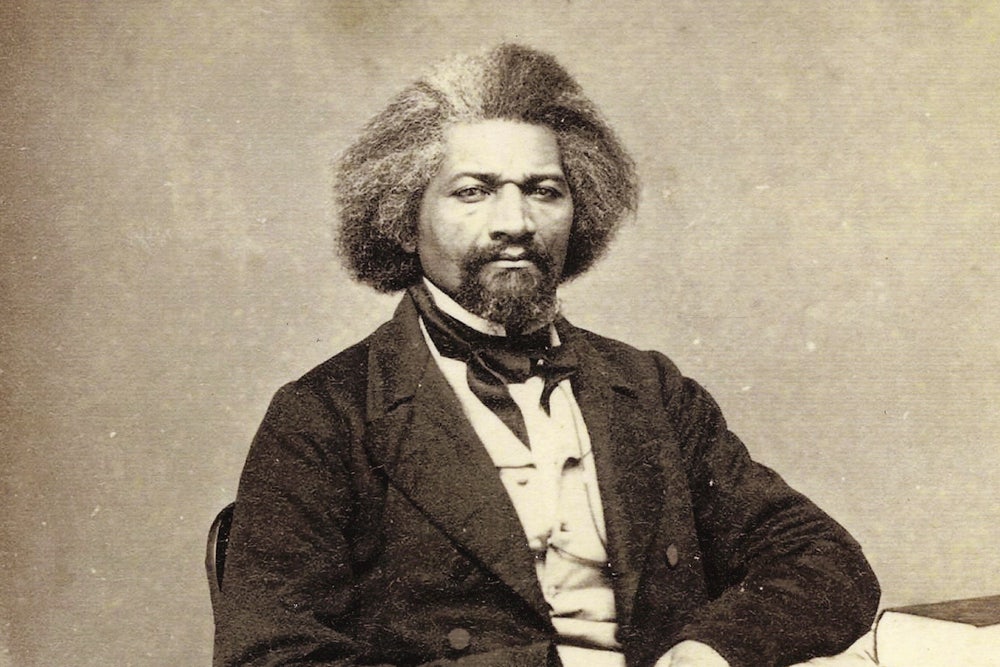

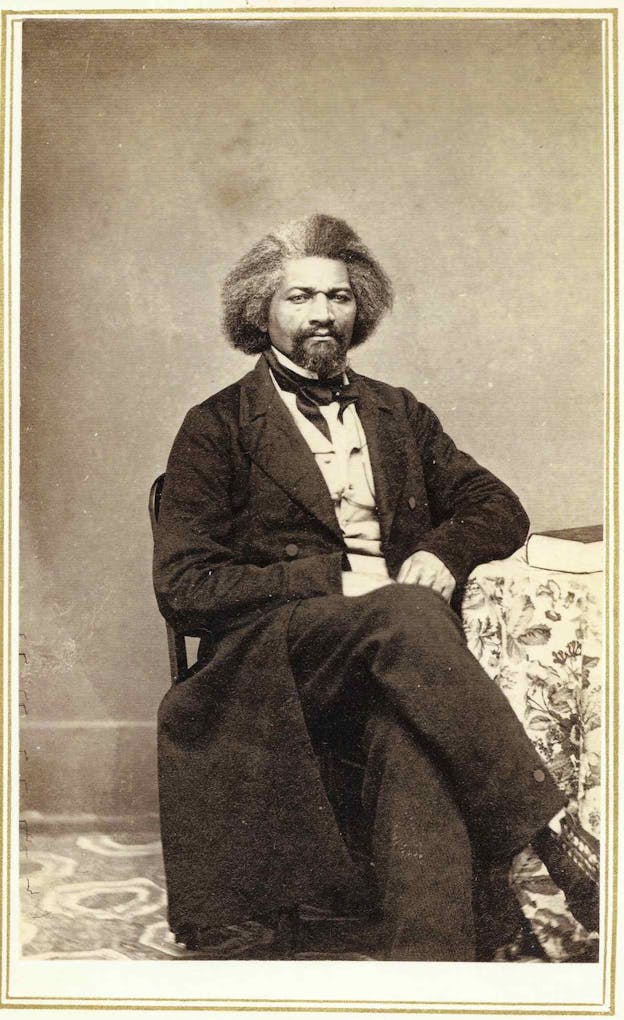

Towards the end of the late nineteenth century, Arabella Chapman, a young African American woman from upstate New York, began to collect and mount personally meaningful tintypes and cartes de visite in a set of small, leather-bound albums. Frederick Douglass appears on page thirty-three of Chapman’s first album—opposite the stern-faced abolitionist John Brown. Douglass is seated in a high-backed wooden chair, wearing a black suit, his hands in his lap, offering a direct, level gaze outward. One elbow is propped up on a side table, and his body is open to the viewer and slightly turned. A plain, white wall is in the background. Such an image conveyed a powerful, dignified seriousness, a certain kind of formal grace. This was a portrait meant to move minds and hearts.

Douglass, we learn in Picturing Frederick Douglass: An Illustrated Biography of the Nineteenth Century’s Most Photographed American, was convinced of the importance of photography. He wrote essays on the photograph and its majesty, posed for hundreds of different portraits, many of them endlessly copied and distributed around the United States. He was a theorist of the technology and a student of its social impact, one of the first to consider the fixed image as a public relations instrument. Indeed, the determined abolitionist believed fervently that he could represent the dignity of his race, inspiring others, and expanding the visual vocabulary of mass culture.

Picturing Frederick Douglass documents the wide range of images of Douglass that have shaped our sense of the man. The first part of the book lays out striking photographs taken over the course of his long public life, presenting them as detailed, reliable, historical artifacts. New, cheaper techniques of reproduction, Douglass believed, allowed for a truer, more precise impression of the person on display. They also made it possible for the subject of the photograph to determine, to some extent, how people read and understood the image. Frame by frame, the authors of the volume show how carefully Douglass tried—in an age where, for so many people of color, this was simply unimaginable—to control meaning.

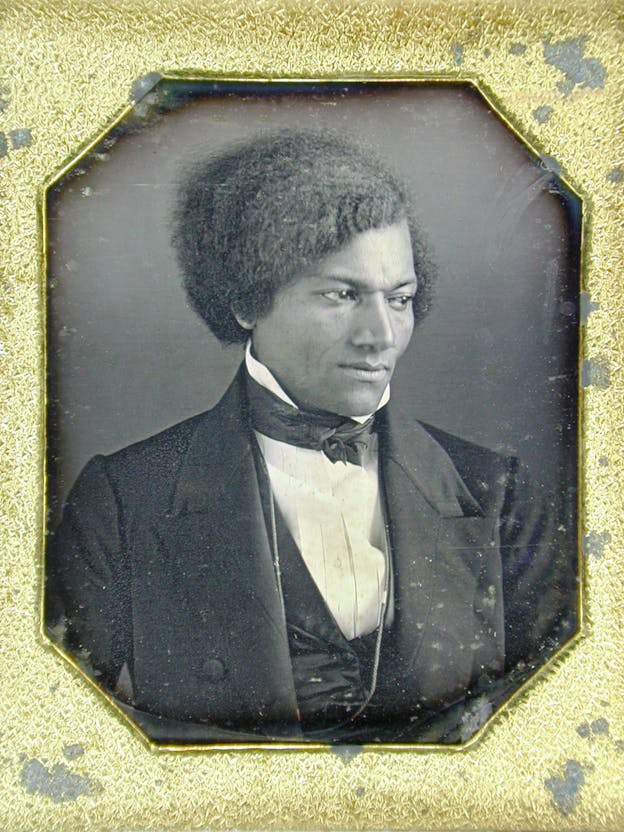

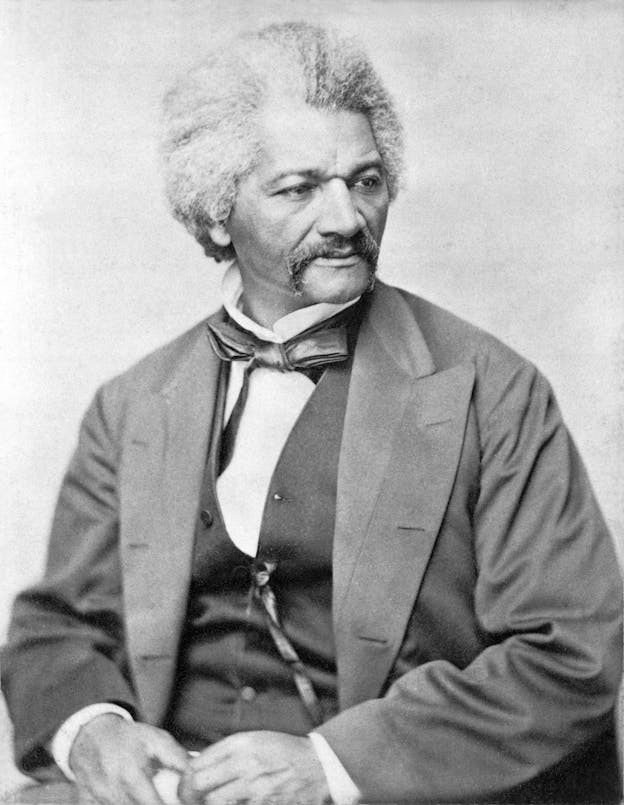

He developed genres of his own representation, each with a particular aim, reproducing a set of postures and wardrobes in various sittings so perfectly that one often needs a magnifying glass to see the fine-grained distinctions. A hand closed in one portrait is open in another. A wrinkle in a vest is just slightly different here.

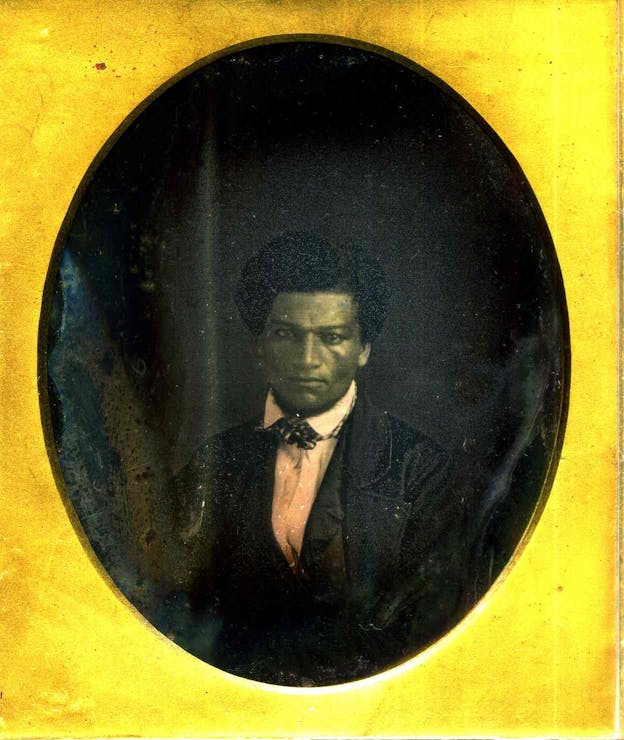

Departing from Victorian convention, he set aside big, busy backdrops, and emphasized a certain kind of politicized minimalism, with the lens zeroed in on his face, his body, and his extraordinary presence. A formal look at Samuel Miller’s 1852 daguerreotype of Douglass, for instance, notes that the center of the image is abolitionist’s stern, tight-lipped mouth. After this, the eye moves up, to the furrowed bridge of his nose, and to his serious gaze. The background is blank. The tight, oval frame of the image trims off any distracting—and, to Douglass, perhaps irrelevant —minutiae. The overall effect is stern, sincere, moving. This is an image meant to convey character.

Picturing Frederick Douglass also considers the importance of other 19th-century representations of Douglass—those not based on photographs but on sketches, so we get to see paintings and cartoons and marble busts, images that serve, the authors suggest, as a sort of “counterbalance,” with “distortion” replacing “accuracy.” In one section, we see the illustrations from the 1881 edition of his autobiography, The Life and Times of Frederick Douglass. In contrast to prevailing stereotype of servile, buffoonish minstrel characters, the seventeen engravings used by the public appear to show a tall, bold, figure, possessed of extraordinary character, revealed in his Victorian posture and comportment. And yet Douglass himself loathed the engravings as inherently false and crude. He preferred the accuracy of the modern photograph to the impressionistic feel of the sketch.

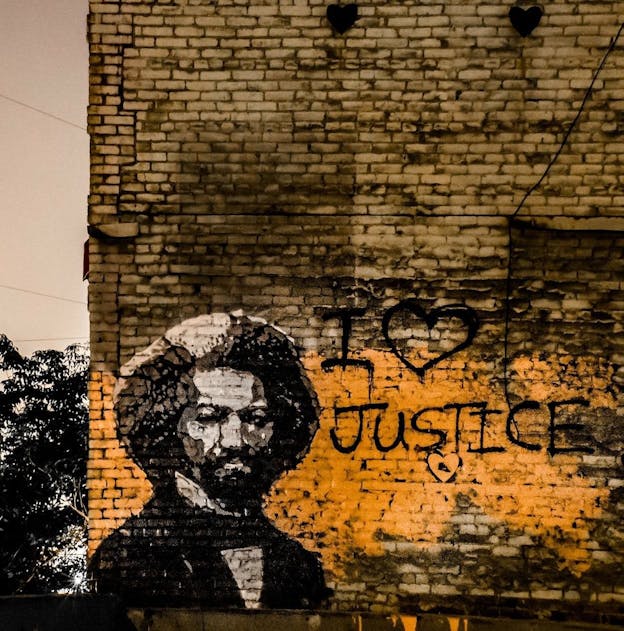

Perhaps the most exciting images in the book are those that show us how these 19th-century portraits became, over the decades that follow, a part of the symbolic surround of the modern American landscape. We get to watch as the formal Gilded Age photographs of Douglass become post Civil Rights murals in a cityscape he could scarcely have imagined. The younger “militant” Douglass appears somewhat more regularly in contemporary paintings, drawings, and statues, while the older “statesman” Douglass is more commonly featured in public murals, of which there are a great many. Certain portraits of Douglass—those by Samuel Fassett (1864), Matthew Brady (1877) and Carl Caspar Giers (1873)—appear in murals as far away as Belfast, as near to home as the local Grenville High School in Cleveland, Ohio, and as ubiquitous as several different postage stamps.

The words in this highly visual book are perhaps even more powerful than the images. Reprinted in full, Douglass’s essays on photography—“Lecture on Pictures” from 1861, “Age of Pictures” delivered in 1862, “Pictures and Progress,” delivered at some point between 1864 and 1865—show how closely connected, for him, were the ideals of justice, uplift, and photography. The “picture-making faculty,” Douglass writes in “Lecture on Pictures,” “is a mighty power.” Mighty, he continued, because it allowed anyone to make their “subjective nature objective,” because it could demonstrate the inherent humanity of men and women branded as slaves in the Confederacy, because it could honestly capture the inner, indomitable spirit of the sitter, and because it could push that compelling verity out into the world as inspiration.

Despite his fervor, Douglass believed that photographs were necessarily “conservative,” because they incorporated celebrity, turning “the author” into a commodity with a reputation that could be difficult to change. In the photographic age, every person who “publishes a book, or peddles a patent medicine,” he argued, whether “handsome or homely, manly or mean,” was using a portrait in their advertisements. Such images, though, transformed the individual into a “fixed fact,” or a “public property,” so that audiences, readers, and consumers would come to expect every detail of the portrait to be unchanged forever. Public figures had to wrestle with the way that their scripted, staged image could sometimes take on a life of its own.

But photography, for Douglass, was also a reflection of reason and progress. Humankind alone, he insisted in “Pictures and Progress,” was capable of photography as an art form, and capable of the criticism of the good and the bad within that medium. More importantly, pictures conveyed a precision akin to religious truth, an affective prerequisite for social movements. “The few think, the many feel,” he reminded his listeners, “the few comprehend a principle, the many require an illustration.” Ideas alone were not enough to galvanize the public into action. To do that, one needed to deploy art, to broadcast “the soul of truth.”

As Arabella Chapman’s albums reveal, Douglass’s sense of the power of photography was spot on. Formal and stylized, her carefully assembled archive represents the family as a respectable if not revered thing, as something worth curating in a small, delicate album. But it also reveals a flattening landscape, a sense that gods and mortals could be bound together between the same two covers. Her albums include portraits of family members, friends, and other intimates alongside images of more distant and famous men and women of the era. And this collection reminds us, as well, of the democratic, revolutionary power of the photographic image, of the sense of magic that often accompanied the collection of the image of those who labored to change the world.

This is an interesting moment to be thinking about such things, of course. These days, even disposable, cheap flip phones have built in cameras, and with the press of a button, any picture taken can be instantly sent around the globe. We dismiss formal portraits, too, as stiff, awkward, forgettable things. We have overlooked what it meant, in the age of slavery and its aftermath, to see a demonstrably literate, dignified, serious representation of a person of color, to see the logic of racial inferiority disproved in a single, crisp image.

Overlooked, that is, until the next tragedy, the next deadly encounter between the police, or a would-be security guard, and a young African American or person of color. Then, with a suddenness that can still surprise us, there is a search for an image that can define the life that has been lost. Casual Facebook and MySpace profile headshots are subject to a journalist’s screen-grab. An old mug shot, if it exists, returns, like a repressed memory. Occasionally, a photograph of the wrong person is used. But almost invariably, in the end, a very formal school portrait appears, as if by miracle. There is a shirt and tie or a graduation gown, a streaky sky-blue background, ad a serious look. Such an image—an echo of Douglass’s portraits—then becomes one regular backdrop on news reports. It gets pressed onto t-shirts and buttons worn by the victim’s family. It gets printed on the small hand-made signs posted next to the flowers and candles that mark the site of public death. It becomes a template for a mural, for art, for commemoration. It compels movement. And it reminds us that there is much more work to be done.