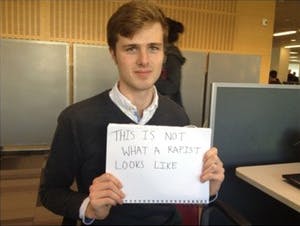

The photo of George Lawlor that went viral in the past week shows him seated in what appears to be a computer lab. The collar of the white shirt he’s wearing underneath a gray V-neck sweater could have used an iron, but so could most of the clothes I wore at his age. He appears pretty clean otherwise: Slender, shaven and wearing a side part in his neatly styled brownish-blond hair. His mouth appears stuck between superior and disdainful. The young, white British student at Warwick University looks preppy, perhaps even conservative, if you choose to judge people by their appearance. It’s clear that Lawlor felt quite judged, and he chose this photo to express his feelings about it. In his hands he is holding a torn-out piece of notebook paper with the words “THIS IS NOT WHAT A RAPIST LOOKS LIKE,” written in black ink, and in full caps. Looking at the photo, I considered the other side of his assertion: What does he think a rapist looks like?

Lawlor never made that clear last Wednesday when both the photo and his accompanying screed was published in The Tab, a news site for students in the United Kingdom. In the post, Lawlor describes in florid detail the joy of receiving an invitation to an event of Facebook. (“Is it a house party? Is it a social? All the possibilities race through your mind,” he wrote.) But Lawlor was not so enthusiastic about clicking on that red notification we typically see at the top right corner of our Facebook page and discovering he’d been summoned to a training session led by the I Heart Consent campaign, a burgeoning education effort that, per its site, “aim[s] to facilitate positive, informed and inclusive conversations and activities about consent in universities and colleges across the UK.”

Lawlor’s “crushing disappointment” that this wasn’t an invite to the latest shindig or pub crawl was palpable—but he began, as do most people about to say something horribly ignorant, offensive or impolitic, with a qualification. “Let me explain, I love consent,” he wrote. “Of course people should only interact with mutual agreement, but I still found this invitation loathsome. Like any self-respecting individual would, I found this to be a massive, painful, bitchy slap in the face.” Calling the Facebook invite “incredibly hurtful” and the “biggest insult I’ve received in a good few years”—he’s 19—all while using vulgarities to condemn people who were taking active steps towards ending sexual assault. After spending several words telling us what a great guy he is, Lawlor, without any hint of irony, slurs I Heart Consent as “smug, righteous, self-congratulatory.” The meat of Lawlor’s argument asks us to sympathize with him as he gives those anti-assault educators the tough love he feels they need. “I feel as if I’m taking the ‘wrong’ side here, but someone has to say it—I don’t have to be taught to not be a rapist. That much comes naturally to me, as I am sure it does to the overwhelming majority of people you and I know.”

I am not so sure.

In her recently published book Asking For It: The Alarming Rise of Rape Culture—and What We Can Do About It, author Kate Harding recommends we embrace an ostensibly horrible reality: That every boy is at risk of growing up to become a rapist. She makes clear that boys, by their nature, are not rapists by nature or fundamentally evil or misogynist—these are learned behaviors. In America, “we live in a rape-supportive culture,” Harding writes. “Boys have to grow up here, too.”

Where is “here”? Per Harding, it’s in a culture of “aggressive masculinity that reviles the feminine,” one so pervasive that we need to teach boys not to rape. That sentiment angers people, as we saw last year after political strategist and writer Zerlina Maxwell caught hell for saying as much on Fox News two years ago. Rape culture makes it so that we need to teach boys and men about consent, but many of those boys and men can’t grasp the necessity of that...because of rape culture. And as it is with racists, it is with rapists: Being suspected of being one, or implicated as having the potential for being one, remains as insidious (or more) than the act itself. Male feelings matter, it seems, more so than female security.

With respect to our college campuses and the issue of sexual assault, America isn’t terribly different from the UK. There is the oft-quoted (and debated) “one in five” statistic about reported U.S. campus assaults put forth earlier this summer by The Washington Post, and cited by President Obama and Vice President Biden alike. Another survey by the Association of American Universities—150,000 students across 27 schools—that was released just last month found that 23 percent of undergraduate women claimed that they had been survivors of sexual assault or had been subjected to sexual misconduct such as unwanted touching. (The AAU survey also noted the drastic undercounting of rape reports that schools receive.) But a January report in The Telegraph indicated that nearly one of every three women attending university in Britain have “endured a sexual assault or unwanted advances.”

Lawlor, in his rant, seems to at least grasp that sexual violence is a problem. “I’m not denying there have been tragic cases of rape and abuse on campuses in the past,” he wrote, “but do you really think the kind of people who lacks empathy, respect and human decency to the point where they’d violate someone’s body is really going to turn up to a consent lesson on a university campus?” That’s not a terrible question, actually. It stands to reason that a person predisposed to preying upon and raping women would not show up to be reeducated by a group which seeks to further understanding of sexual consent. But who is he to say that this is whom I Heart Consent sought to reach?

The Tab published a response to Lawlor on the same day from Josie Throup, the organizer of the I Heart Consent workshop. “The truth is, I’m not sorry my workshop made this writer feel uncomfortable,” Throup wrote in her post. “The first time I was confronted with the statistic that 80 per cent of rape survivors know their attacker, I felt the same. When I thought about this and realised most rapists are normal members of society, I felt sick. I still do feel sick when I think about the cycles of abuse perpetrated by partners, parents, and friends of people I know. Self-styled ‘decent, empathetic human beings’, like this writer.”

Throup made it clear that she wasn’t accusing Lawlor of having been a rapist; just that we should allow for the fact that a rapist could look like him. She noted examples of rape culture not only in the media, but there on the Warwick campus, concluding that another part of the workshop’s purpose is “empowering survivors and giving general students the chance to learn how their actions form part of a culture and how they can make those actions more supportive to survivors of sexual assault at Warwick and beyond.” I don’t know if all that was in the Facebook invite that upset Lawlor. However, I suspect he may have learned that had his first impulse been to attend the event, and not to preemptively condemn it from a place of entitled ignorance.

Having been a columnist for my college paper, I’ve long understood the peril of being held to account for what you’ve written during a time when you’re still learning how to think. (I wrote 40 columns for The Daily Pennsylvanian over five semesters; perhaps because it’s been a while, they’ve all fallen out of the archive but this one.) Considering, though, that college students themselves are largely the perpetrators of campus sexual assault as well as the victims, we have to take seriously what they express.

Lawlor, in writings on the blog Omnipolitical, has declared himself to be a libertarian and a free-speech absolutist, and defended the right for someone to be homophobic. He also has shared just how hard it is out here for a skinny dude. “The worst case scenario is when this happens after a girl asks you to lift something,” he wrote in The Tab this past September. “Skinny girls never have this problem: they can always ask someone else to do it without losing face.”

But now, one month after Lawlor bemoaned that particular gender double-standard, he has publicly exacerbated another. Whereas he may get fun of when asked to lift a couch, Lawlor and white, heterosexual men like him tend to be taken seriously when they complain about being harassed, assaulted, and victimized. We know that isn’t the case with women. Part of that is attributable to blatant sexism, sure, dismissible as pure evil. But a lot of it is due to the fact that a lot of men do not understand what rape, sexual assault, and other associated misconduct even are. Being men, we’re reminded daily how entitled we are to being correct, or to deciding what is correct. And heaven forbid a workshop (or even just an invitation to one) question our assumptions and preconceptions about such things.

In a follow-up interview on YouTube with anti-feminist Canadian journalist Lauren Southern, Lawlor elaborated on the phenomenology of rape. “The fact of the matter is that rapists know what they are doing,” he told Southern. “Most people know right from wrong. I am willing to wager that most rapists know right from wrong.” It stands to wonder how could he possibly know any of that. While I’ll grant that the existence of consent workshops may give the impression that a rapist may be somehow confused about what he is doing, he’s actually pointing out why they are so necessary.

“[Lawlor] is the perfect example of why we need consent education,” said Sofie Karasek, the Director of Education at End Rape on Campus, a non-profit seeking to do exactly that. “Saying that you don’t think you look like a campus rapist mirrors the lack of responsibility and accountability that perpetrators often display.” Karasek also told me that Lawlor, contrary to racial stereotypes, fits a typical profile of a campus rapist: A white man presenting as wealthy. “Believing the myth that rapists jump out of bushes in the middle of the night is easier than admitting the truth: That most perpetrators are people who you know. Moreover, if someone who fits the statistical profile of a campus rapist doesn’t think that they ‘look’ like a rapist, it underscores that some men think that they are exempt from responsibility and accountability, which is at the heart of the problem of campus rape.”

I was a rape crisis counselor during my senior year of college, so I’ve done workshops about consent myself. Since then, I’ve met men young and old who remind me of Lawlor, getting pissy when someone dares imply that they haven’t already learned everything they needed to know about women and consent—or done enough just by being Good Guys to stop the epidemic of sexual violence.

Men who espouse basic tenets of feminism and oppose sexual assault merit neither the assumption of omniscience nor a medal. Lawlor may very well become a valuable ally, once he gets over himself. But as long as people like him prioritize a man’s fragility over a woman’s safety, they’ll remain part of the problem.