Two years ago, a group of international researchers led by University of Queensland's John Cook surveyed 12,000 abstracts of peer-reviewed papers on climate change since the 1990s. Out of the 4,000 papers that took a position one way or another on the causes of global warming, 97 percent of them were in agreement: Humans are the primary cause. By putting a number on the scientific consensus, the study provided everyone from President Barack Obama to comedian John Oliver with a tidy talking point.

That talking point put climate deniers in a bind. They have successfully delayed political action for years by making it seem like there's still a scientific debate over anthropogenic warming. But when confronted with a statistic like this one, they have been forced to take a different tack: dispute the statistic itself.

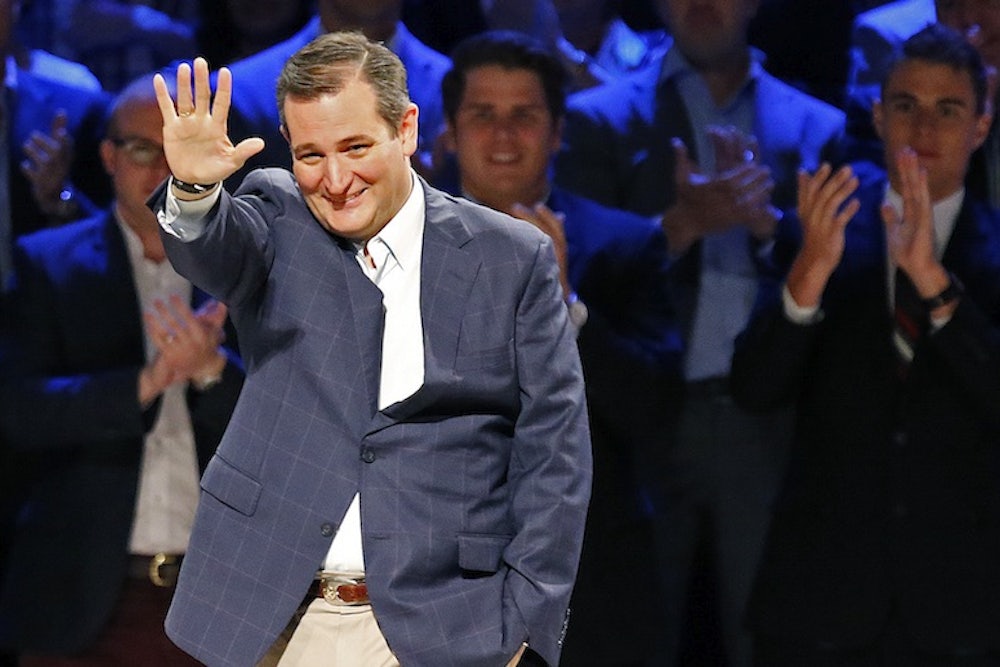

They're the 97 percent truthers, and Texas Senator Ted Cruz is leading the recent charge. At a hearing in early October, the GOP presidential candidate peppered Sierra Club President Aaron Mair with questions for ten minutes about the so-called 18-year pause in global warming—a point that's been thoroughly debunked. Mair replied to Cruz’s repeated demands to retract his testimony on climate change by citing the 97 percent consensus, which Cruz brushed off by saying the “problem with that statistic that gets cited a lot is it’s based on one bogus study.” Cruz added that the point was irrelevant to the debate. “Your answer was, pay no attention to your lying eyes and the numbers that the satellites show and instead listen to the scientists who are receiving massive grants who tell us do not debate the science,” he said.

Conservative sites celebrated Cruz's questioning. National Review ran two stories, one claiming “Ninety-seven percent of the world’s scientists’ say no such thing” and another that “the 97 percent stat is pure public relations b.s.” The attempts to discredit Cook's study are as old as the study itself. Rick Santorum, another Republican presidential candidate, contested the 97 percent consensus in late August. "That number was pulled out of thin air,” he told Bill Maher. The Wall Street Journal took issue with it last year, arguing that these peer-reviewed studies never said manmade climate change was “dangerous.”

The main criticism of Cook's study is that it omits the vast number of papers that take no position on global warming's causes. That's true: Cook’s study of the 12,000 abstracts found that 66 percent of them took no position, so he excluded them in calculating the percentage. As Cook explained in an online video, he omitted these papers because abstracts are short summaries that "don’t waste time stating something they assume their readers will already know"; just as most "astronomy papers don’t think it necessary to explain that the Earth revolves around the sun," he said, "nowadays most climatology papers don’t see the need to reaffirm the consensus position.”

The deniers' criticism hardly discredits his study. After all, roughly 4,000 of those abstracts did take a position, and 97 percent of them endorsed anthropogenic warming. And it's hardly the first study of its kind.

Cook's finding is backed by a field of literature. A paper in the journal Science published a decade earlier by Naomi Oreskes found 75 percent of peer-review literature from 1993 to 2003 agreed on man’s role in global warming. That percentage has only risen as the scientific study on climate has progressed. In June, a longtime researcher of the subject, National Physical Sciences Consortium director James Powell, found that 97 percent might be too low. His paper, which has not yet been published, found 99.9 percent of the field agreed in 24,000 peer-reviewed papers published in 2013 and 2014.

“The fact that each of these studies have used completely different methods to arrive at the same result demonstrates just how robust the overwhelming consensus on climate change is,” Cook said, pointing out that these studies have relied on techniques like directly surveying climate scientists, analyzing public statements, and examining peer-reviewed papers. All these approaches confirm the same point on the vast agreement.

Even if you want to ignore the consensus literature, the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change—which includes the most robust panel of respected climate scientists in the world—said in its most recent and fifth assessment that it has 95 percent confidence that humans are driving warming (equivalent to the scientific certainty that cigarettes cause health problems).

That's not the only case deniers make against the 97 percent figure. They argue that if you include non-experts (academics in fields unrelated to climate change) or only look at the studies that say global warming dangerous, you'd get a much lower number. There are some obvious problems with these arguments: Shouldn't expertise in a field matter? And how to define "dangerous" warming was outside the scope of Cook's study. After all, the whole point of the study was to answer a simple question that cuts through the rhetoric of climate politics.

All this debate over one statistic might seem silly, but it's important that Americans understand there is overwhelming agreement about human-caused global warming. Deniers have managed to undermine how the public views climate science, which in turn makes voters less likely to support climate action. According Gallup polling, only 60 percent of Americans think that most scientists believe climate change is occurring.

Yet another study shows how that number could rise. A PLOS One paper from Princeton, Yale, and George Mason University researchers took a step back to consider whether the 97 percent argument is effective at changing public opinion. Researchers gave 1,000 subjects various messages in pie charts or statements, all of which emphasized the 97 percent consensus. Respondents who received this message were more likely to accept climate change, and were also more likely to think of it as a problem. “Repeated exposure to simple messages that correctly state the actual scientific consensus on human-caused climate change is a strategy likely to help counter the concerted efforts to misinform the public,” the authors wrote.

The researchers called 97 percent a “gateway belief” that could even convince Republicans that climate change is a problem. It's only a matter of time before Cruz publicly questions that study's findings, too.