When a penthouse apartment in One57 sold for over $100 million last year, it broke the record for Manhattan’s most expensive apartment. A steel-and-glass luxury apartment tower rising one thousand feet in Midtown, One57 is one of the most visible additions to the New York skyline. Shortly after it was completed New York magazine’s architecture critic Justin Davidson called it “clumsily gaudy,” and Curbed deemed it the worst building of 2014. Along with 432 Park Avenue, a super-luxury residential tower taller than the Empire State Building and One World Trade (minus their antennae), One57 has come to symbolize luxury in its crudest form. Who could afford and would want to inhabit such a place? Yet some of my favorite buildings in the city—the Ansonia, the Dorilton, the San Remo, and 299 West 12th Street—once too aspired to be the tallest, grandest, and most expensive.

Of those buildings, the Dakota stands as a high point of antiquated luxury and occupies a particularly vast slice of New York City cultural lore. It’s where Tchaikovsky was entertained during his tour of the US in 1891. Nureyev slept there in a flamboyant Elizabethan bed, and, later, Lauren Bacall could be found chatting with Albert Maysles or Leonard Bernstein in their shared courtyard. The building, adorned with cast-iron dragons and a sentry, has many macabre associations: In Polanski’s Rosemary’s Baby, Mia Farrow was assailed there by a Satanic cult; John Lennon was shot outside on December 8th, 1980; and Boris Karloff, who played Frankenstein, lived there in the 1930s.

Though I take every visiting friend to admire it, I’ve never been inside the Dakota. The lofty stone archway and wrought iron fences make the entrance feel more like a fortress than a residence. Though I browse StreetEasy listings for the building and contemplate posing as a potential buyer, I can’t think of anything more uncomfortable than facing the Dakota’s co-op board, which has turned down applications from Billy Joel, Cher, Melanie Griffith and Antonio Banderas.

Andrew Alpern, a lawyer turned architectural historian, has written a book for the outsider who longs to gain access to the marble halls of the inside. His upcoming book The Dakota: A History of the World's Best-Known Apartment Building spends only one chapter on the building’s famous tenants (a subject better left to Stephen Birmingham’s Life at the Dakota). The rest of its pages are consecrated to details that allow the reader to reconstruct the Dakota from its foundation to its roof terrace in his or her imagination. There are chapters on the building’s floor plans, the architect who designed it, its financier, the construction, which took four years and between $24 and $47 million dollars (in current values), and the impact it had on luxury apartment design. With the help of Christopher Gray, the prolific architectural and urban historian and former “Streetscapes” columnist, Alpern supplies us with painstakingly acquired details that might have been relegated to the appendix of a different book.

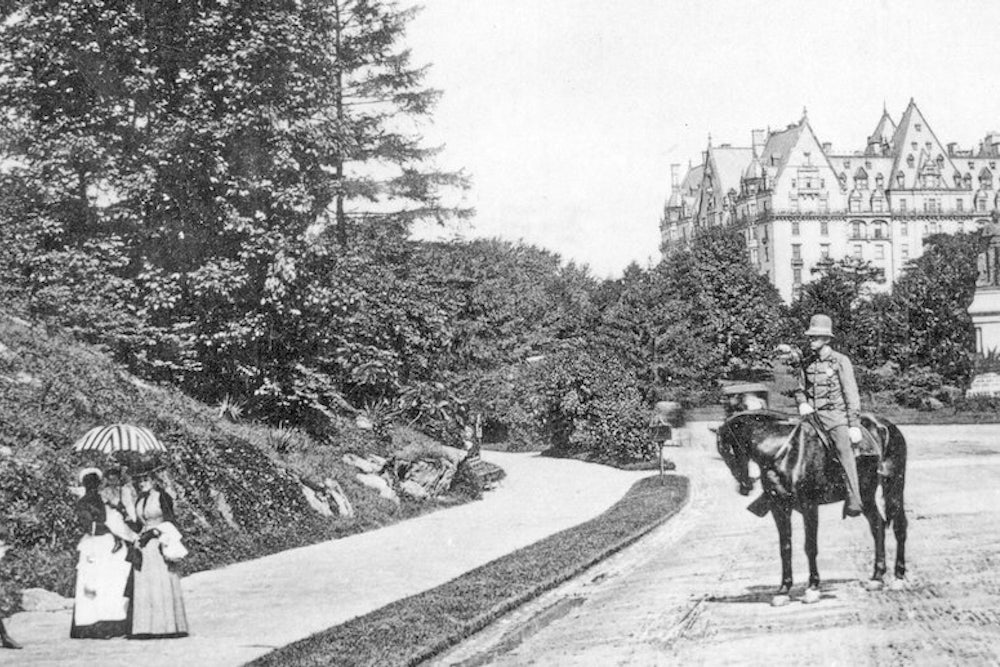

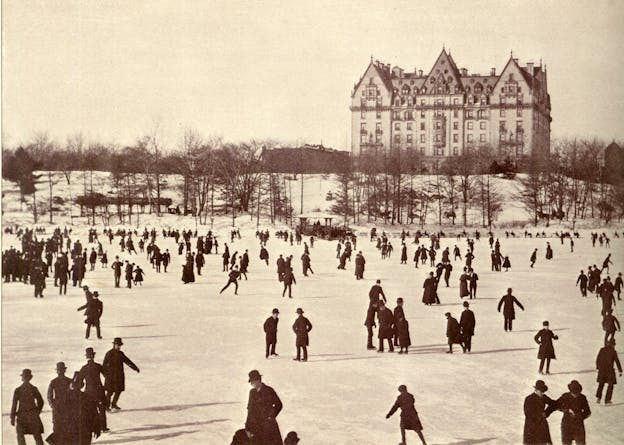

The Dakota, said to have been named so because it was originally so far north and west that it may as well have been in frontier territory, was built between 1880 and 1884. It was designed by Henry Janeway Hardenbergh—who went on to build the Waldorf Astoria, and Plaza Hotels as well as the Con-Ed building—and financed by Edward C. Clark, a businessman who made his fortune in the Singer Sewing Machine Company. At the time of the building’s completion, the Upper West Side was largely barren plots of granite separated by marshes and wandering goats. An 1889 issue of Frank Leslie’s Illustrated Newspaper describes the Dakota as a “great overshadowing mass of brick and stone” which rises against “the humble cottage that was built upon the plot when it was all a part of a garden or farm.” Alpern knows that, no matter how often we see it, we are still shocked to see that a little over a century ago Manhattan as we know it is unrecognizable.

The greatest drama of The Dakota comes in the form of a love story. Alpern adores the businessman and real-estate investor Edward C. Clark who planned and financed the building’s construction, but died two years before its completion. His devotion first becomes apparent when he contrasts Clark with Isaac Merritt Singer, his business partner in the Singer Sewing Machine Company: “where Clark was refined, self-effacing, hard working, and religious; Singer was uncouth, a self-promoter, indolent, and completely amoral.” This statement prefaces his belief that the success of the sewing machine company is entirely Clark’s. In later passages Alpern praises Clark for “foresight lacking in ordinary people” and for being “prescient” and a man who “saw big pictures that lesser men couldn’t even imagine.” He creates value “outside the box”; a few chapters earlier, Alpern compares him to Steve Jobs.

Nevertheless it is clear that Clark succeeded where many others had failed: he was the first to predict the tastes and needs of an emerging urban bourgeoisie. Edward C. Clark went to great lengths to cater to the sort of people who would otherwise buy a townhouse. Before the Dakota, multi-family residences were either transitory housing where the affluent avoided their families, or crowded accommodations for the working class. By the 20th century apartments were the real estate gems of bankers, brokers, and doctors. Clark allotted the cramped, sultry top floors to servants, and kept all coal, groceries, and deliveries underground, so that they would not be seen from the courtyard. On some floors the ceilings are over 15 feet high, and each apartment is bounded in thick walls (some over a foot of brick) to create a sonically-impenetrable environment. All of this was tailored to the sensibilities of private and family-oriented Americans who entertained lavishly.

With the help of architect Mia Ho, Alpern supplies one of the most useful resources for the curious outsider who wants to imagine living in the Dakota: detailed floor plans for all ten stories. Unlike photographs, which collapse space and only give the sense of the building room-by-room, a floor plan gives you, in approximate terms, the actual dimensions, arrangement, and use for each room.

They also show how innovative the Dakota was. Pre-Dakota apartments had bedrooms leading awkwardly from double doors to the living room, windows facing brick walls and dim air shafts, and rows of small, poorly lit bedrooms. By contrast, a living room in the Dakota is often followed by a dining room, study, or hallway, then followed by the bedrooms, nearly all of which are arranged to face outwards. It is the less intimate spaces—kitchenettes, dining rooms, and studies—that face the building’s central courtyard. Compared to the intuitive, commodious, elegant layout of the Dakota, the earlier 1876 Osborne (now demolished) and Windermere Apartments (soon to be a hotel) seem charmingly dysfunctional.

Compared to our most recent batch of luxury apartments, Clark’s idea of luxury seems quaint and, in a way, modest. He didn’t build the Dakota for Cornelius Vanderbilt or John D. Rockefeller but for the professionals just beneath them on the social ladder. One57 and 432 Park, on the other hand, cater almost comically to the international super-rich. The units take the same, indiscriminate approach to luxury as a Trump Hotel: floor to ceiling windows, monoliths of marble, cavernous open layouts and the highest possible viewpoint. It seems unlikely that anyone who can afford one of these apartments actually intends to make it a permanent residence the way Yoko Ono did with the Dakota. The design is intended to signal instead just what money can buy—and how frictionlessly large sums of money can move around a globalized world. Likely these units until will change hands about as often as stocks do, merely signifying the handing off of a good investment from one businessman to the next.

It is hard, looking at the luxury buildings that followed it, to return to the Dakota as fondly as I might have before. Where there used to be a sentry box, iron gates, and servants quarters, there are now doormen and separate entrances for the less wealthy residents. In this the Dakota is much like any luxury residence: The only real difference is that I happen to consider the Dakota genuinely beautiful and 432 Park an eyesore. Even Andrew Alpern, perhaps the Dakota’s foremost devotee, has a taste for the new, dispiriting towers: his previous work includes Holdouts!: The Buildings That Got in the Way, a book co-authored with the late Seymour Durst, of the Durst Organization, celebrating the ingenuity of real estate developers over stubborn hold-outs.