Orhan Pamuk’s recent protagonists—sensitive, saturnine, stupid men—love as if their entire lives depend on it, and Mevlut Karataş is no exception. Mevlut, a street vendor whose life story animates Pamuk’s capacious new novel, A Strangeness in My Mind, is an incorrigible romantic. He spends three years writing love letters to a girl whose eyes transfix him at a wedding, only to find out that as they elope, the wrong girl has turned up. She doesn’t have the same eyes. Mevlut’s cousin, it turns out, has tricked him into addressing his letters to the older sister of his beloved, and yet Mevlut says nothing and marries her anyway. Amor fati—love your fate—this novel suggests, and everything will turn out fine.

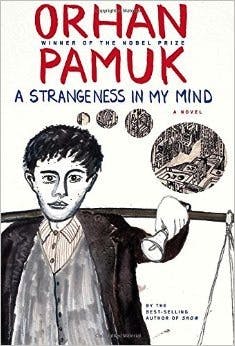

Eschewing the baroque sleights-of-hand that characterize his earlier fiction, Pamuk gives away these plot details in the novel’s first few pages. (Hence the absence of a spoiler alert above). This novel confirms Pamuk’s drift towards the straightforward realism preferred by the avatars of 19th-century European literature. “I’m doing what Stendhal did, what Balzac did,” Pamuk told Pankaj Mishra in this magazine in 2013 while discussing his research for this novel, and he’s not far off in that self-assessment. Its postmodern scaffolding notwithstanding, A Strangeness in My Mind is primarily devoted to recovering the memory of a particular journey that many Turks undertook from the village to the big city in the late 20th century.

This is a novel of immigration (within one’s own country) and the hardships and moral dilemmas that invariably attend such sudden, if voluntary, displacement. Mevlut, Pamuk’s first working-class hero, is one such villager who can’t resist the boundless opportunity of Istanbul. He sells boza, a vaguely alcoholic winter drink, along with ice cream; he manages a small café whose workers actively swindle their boss; he hawks chicken and rice until the government impounds his food cart. His employment is always precarious, and this markedly contrasts with the fates of his friends and family, whose relative prosperity is a constant source of consternation for him.

Regardless of his day-to-day struggles, Mevlut finds peace ambling the streets of Istanbul by night. “Walking fueled his imagination and reminded him that there was another realm within our world, hidden away behind the walls of a mosque, in a collapsing wooden mansion, or inside a cemetery,” writes Pamuk. This line, perhaps only betrayed by the reference to a mosque, could have just as easily appeared in Baudelaire’s “The Painter of Modern Life,” and invites comparisons to Pamuk’s contemporary city-walkers in Teju Cole and Enrique Vila-Matas. While critics will disagree on the ethics of a card-carrying member of the Istanbul bourgeoisie ventriloquizing a poor street vendor, this unusual combination of Pamuk’s background and subject matter has yielded a new type: a working-class flâneur, Constantin Guys with a day (and night) job.

“You will see everything without being seen,” says Mevlut’s father, a former boza seller himself. “You will hear everything but pretend that you haven’t…” This makes the boza seller an ideal novelistic subject who naturally has access to the interiors and exteriors of the city. In a way, Mevlut also resembles the novelist, a perpetual loner who exists on the margins of society, constantly recording and observing things that are lost on the mercifully less self-conscious. After all, “his favorite thing in the world was watching people go by on the street, inventing stories inspired by the things he saw...”

As Mevlut looks out on the world, he largely gazes inside himself. He is acutely aware that he is different from other people and that something is apparently wrong with his head. Even members of the bourgeoisie, when they deign to converse with him, are shocked to learn the depths of his interior life: how did this simple boza seller write all those love letters, they wonder. The inward nature of Mevlut’s vision is worth noting, since Pamuk’s Turkish characters often internalize the gaze of an imagined Westerner for whom they constantly perform their urbanity. Fascinatingly, this double consciousness is largely absent from A Strangeness in My Mind, though certain ligatures of the Westernization question remain, present in small, daily humiliations: UNICEF’s donation of smelly powdered milk and fish-oil pills to Mevlut’s school particularly comes to mind.

Instead of worrying about the Western gaze on their city, this novel’s Istanbullus largely concern themselves with how the other half in their own city lives. Everyone is constantly dropping in on each other. At one point, Mevlut’s wife takes a job as a live-in maid at the home of a wealthy family and, rifling through their old photographs and letters, starts to see herself in them, discovering that she feels “at once deeply attached to and yet somehow resentful of these people who were laying their private world open for me to see.”

In scenes like this, A Strangeness in My Mind documents the creation of two cities within Istanbul and the widening fissure between them. Before the faceless motor of economic inequality—visible in the gradual changes to the urban landscape but invisible at the structural, policy level—the novel’s characters attempt to rationalize these class disparities to disheartening effect. “God loves some people more,” Mevlut’s childhood friend declares. “Those people end up rich.”

As he enters the 21st century, Mevlut becomes a walking anachronism. Sales are down, and if people buy boza from him, it’s largely to indulge their own nostalgia for a past they scarcely remember, a past they’ve maybe never even experienced. When the haughty bourgeoisie invite him up to their apartments for boza, they mostly poke fun at the faux-naïf before them, the relic of the past who is mixing ingredients (and performing his provincial, religious identity) for them in their living room. From encounters like these, it’s clear that Mevlut seeks not merely to sell boza to his customers, but rather to transmit a message to his city from its past, before it’s too late. A Strangeness in My Mind continues Pamuk’s obsession with the passage of time and the project of indexing an earlier Istanbul that is at risk of fading away before our eyes.

This novel resembles an oral history of sorts; various first-person voices interrupt and compete with each other, and happily, many of them belong to women. This democratic narrative bricolage may create a certain ceiling for the novel, however. Its sentences, constrained by the demand for verisimilitude, are necessarily less beautiful than those in The Museum of Innocence, Pamuk’s first book after winning the Nobel Prize. Its philosophical inquiries are less sophisticated than those of The White Castle. And this novel’s capacity for suspense is inherently thwarted by the revelation of its plot in its first few pages. Yet, there is something radical to this transparency and paring down. (Strange to say of a novel 600 pages long, but true.) This is Pamuk’s most accessible work yet, and it may succeed in striking an emotional chord with readers who felt alienated by the theoretical puzzles of his earlier writing.

A Strangeness in My Mind faithfully chronicles how Istanbul became “the capital of the world” over the past fifty years, contrasting the city’s inexorable march towards modernity with Mevlut’s own struggle to carve out a small piece of the city for himself. The strangeness in his mind—the loneliness that sets him apart from others, the penchant for his daydreams to seep into his reality—may prevent Mevlut from getting rich like his friends, but paradoxically it enables him to enter into a deeper communion with the loves and the city of his life… There is perhaps no more honest form of human expression than the cry of a boza seller, and if you listen closely enough to this novel, you may discover a secret history of Istanbul in Mevlut’s song.