On Monday, the marshal of the United States Supreme Court will ask everyone in the courtroom to rise and, as the justices file in through the maroon curtains and take their seats, ask God to “save the United States and this honorable Court.” Before the Court adjourns at the end of the following June, the justices will hear and decide about 75 cases. Some, possibly as many as 50 percent may be unanimous, but the rest will be by a split vote, with the most contentious cases narrowly divided 5-4. (Last term, the unanimity rate was 40 percent.) The big cases include: a challenge of the University of Texas’ use of race as a factor in admissions (Fisher v. University of Texas); a challenge of public-sector employees unions’ use of dues money for political speech with members disagree (Friedrichs v. California Teachers Association); whether the one-person, one-vote rule should rely on the voter-age population or the general population (Evenwel v. Abbott); and a death penalty case involving race discrimination (Foster v. Chatman).

The newspapers and other media outlets covering the Court will focus on the majority opinions, of course, because those will determine not only the outcome of these particular cases but all other similar issues in the foreseeable future. Some of us, though, will be looking at the dissents at least as closely. We know that some of the most influential opinions in the Court’s history have been written by those who disagree—who, in the normal language of the justices, “respectfully dissent.” Whether the arguments in any of the dissents this coming term will eventually prevail is impossible to predict; as Harvard Law Professor Mark Tushnet reminds us, only history can determine the great or “prophetic” dissents.

We are so used to the Court deciding a case by a divided vote—with a majority opinion, one or more concurrences, and one or more dissents (there are some cases in which all nine justices have written opinions)—that we forget that until the 1940s over 90 percent of the cases decided each term, sometimes as many as 200 cases, were decided unanimously. Much of the credit for that goes to two early chief justices, Oliver Ellsworth and John Marshall. Between them they did away with the English practice of seriatim, in which each member of the court wrote an opinion. While one might tally the votes to see who had won, it proved far more difficult to determine the jurisprudential theory behind the opinion. Marshall especially believed that if the Court spoke in one voice, its decisions would have greater influence—an idea that many judges on both the federal and state benches still share.

At least until the late 1920s, unanimity proved fairly easy because a majority of the cases before the court had little significance to anyone other than the litigants. Today, nearly all of these cases would be heard by lower—much lower—state courts. As Justice Louis Brandeis said in 1923, “It is more important that these cases be decided than that they be decided right.” But there were dissents that proved more influential than the majority decisions. In a series of cases challenging the emerging Jim Crow regime in the former Confederate states, especially the infamous decision in Plessy v. Ferguson (1896) upholding the doctrine of “separate but equal,” Justice John Marshall Harlan dissented over and over again, famously declaring, “Our Constitution is color-blind, and neither knows nor tolerates classes among its citizens.” It took over six decades before Harlan’s view became the law of the land, starting with Brown v. Board of Education in 1954. (In an interesting twist, conservatives on the Court led by the Chief Justice have used Harlan’s words as a rationale to oppose affirmative action as well as efforts by various school districts to prevent re-segregation.)

In the 1920s, Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr. and Brandeis frequently dissented together. The theories of these two men, especially regarding the First Amendment’s protection of speech, eventually became the standard by which modern courts evaluate free speech questions. Of especial note is the Brandeis opinion in Whitney v. California (1927), which although technically a concurrence, has been hailed by many scholars as the greatest dissent ever written. In it, Brandeis eloquently explained why free speech mattered, not as the abstraction of Holmes’s often cited free market of ideas, but as an integral part of the democratic process by which citizens could learn all sides of important policy discussions. It took nearly four decades before the Court fully adopted Brandeis’s view, but he understood that such might be the case. “My faith in time,” he said, “is great.”

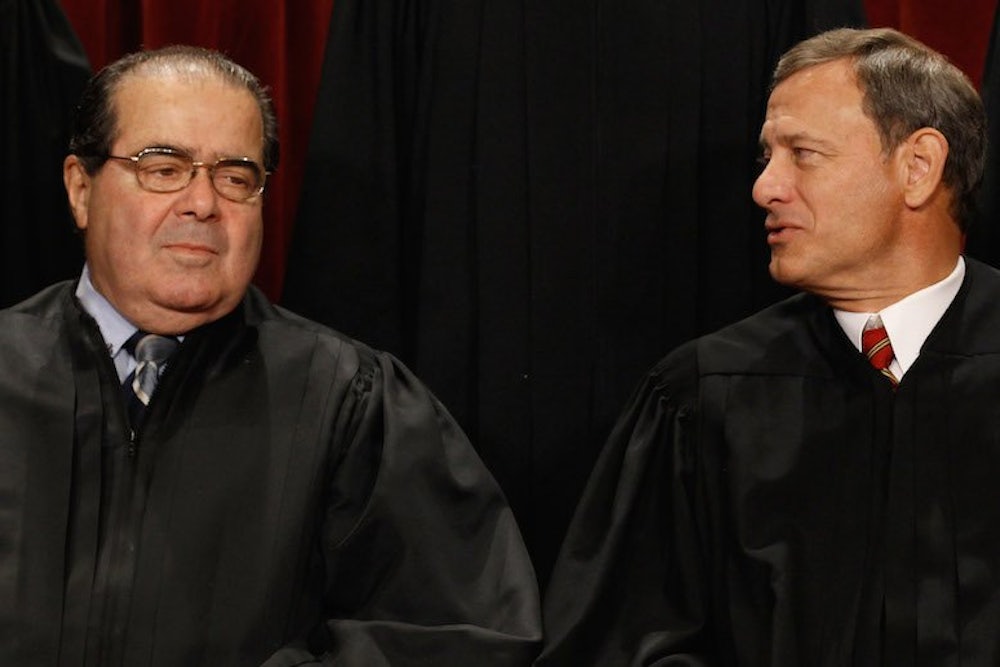

Brandeis penned another prophetic dissent in ‘20s, objecting when the Court upheld the conviction of a bootlegger on evidence secured by a warrantless wiretap. In Olmstead v. United States (1928), he not only changed the entire understanding of the Fourth Amendment’s warrant clause, but also introduced the notion of a constitutionally protected right to privacy. The Court did not fully accept Brandeis’s views until the 1960s, when Justice Potter Stewart declared that the “Fourth Amendment protects people, not places.” As for privacy, there are still some justices and scholars who argue that since the word “privacy” is not found in the Constitution it cannot exist as a right; most people disagree. (In two fairly recent cases, Justice Antonin Scalia struck down convictions for growing marijuana because the authorities had no warrants. In one, police used a device that registered excess heat, and in the other a marijuana-sniffing dog. Scalia’s reasoning was exactly the same as that of Brandeis in Olmstead, but he refused to cite the case because he disagrees with the notion of a right to privacy.)

There are various types of dissents. Some are little more than rants, such as when Justice James McReynolds claimed that the Constitution had been destroyed by a New Deal measure. Others, like many of Justice Felix Frankfurter’s dissents, are pleas to be heard. Most dissents, however, lay out what the dissenter sees as the jurisprudential errors in the majority opinion, and then propose an alternate theory to resolve the matter. In law schools, it is common practice to explicate an important dissent with as much care as the majority opinion, and lower court judges will often use the dissent as a means to avoid following the majority. Moreover, when a similar case, or one in the same area as the original case, comes up to the high court again, the justices will have to take into account the strong points of the earlier dissent. The Holmes and Brandeis dissents on free speech from the 1920s were cited in nearly every First Amendment case that the Court heard for the next four decades.

There are a handful of what have been termed “prophetic dissents,” those that have completely altered the Court’s jurisprudence over time. Harlan in Plessy, Holmes and Brandeis in the 1920s free speech cases, Brandeis in Olmstead, and Justice Hugo Black in Betts v. Brady (1941), in which he argued that the Constitution required assistance of counsel in criminal cases. Unlike Harlan, Holmes, and Brandeis, who did not live to see their ideas accepted, Black was still on the Court when it unanimously decided Gideon v. Wainwright in 1963, and Chief Justice Warren assigned the opinion to Black.

Only time will tell if a dissent will prevail, but I recently did an informal survey of my colleagues in the field of legal history and asked them if they thought any recent dissents might ultimately rise to the status of prophetic. I received a variety of answers, but three opinions led the pack: Justice William Brennan in McCleskey v. Kemp (1987), in which Brennan attacked the racial bias in many death penalty cases; Scalia in Morrison v. Olson (1988), the special prosecutors case where Scalia laid out one of the most intellectually acute analyses of separation of powers; and Justice Ruth Bader Ginsburg in NFIB v. Sebelius (2012), the first Affordable Care Act case, where she attacked the majority’s crabbed view of the Commerce Clause.

Will we get any prophet dissents this coming term? If so, it may be years before we recognize it as such or it has any impact of the Court’s constitutional jurisprudence. And sometimes we get a dissent that is prophetic not in the way its author meant it to be.

In 2013, the Court struck down the Defense of Marriage Act (DOMA), and ruled that the federal government had to recognize same-sex marriages performed in states where such unions were legal. Although Justice Anthony Kennedy tried to keep the decision cabined and even said this case did not deal with the general question of same-sex marriage, Scalia went on a rant and predicted the case would lead to the judicial approval of same-sex marriages, and then laid out how proponents would go about doing it.

Whether he intended it or not, Scalia had provided a blueprint, and the very next day, following his “plan,” the American Civil Liberties Union and other LGBT advocacy groups began filing suits in federal courts attacking state laws and constitutional provisions that limited marriage to a union between a man and a woman. One court after another agreed, and in June, Scalia’s dissent in the DOMA case proved to have been prophetic.