When my daughter was in elementary school, she wore her hair long, and every night before I began reading aloud to her, I sat behind her to comb and then braid it. If left loose during her hours of hectic sleep and dreams, Sophie’s hair was transformed into a great bird’s nest by morning. I especially liked the braiding ritual, liked the sight of my child’s ears and the back of her neck, liked the feel and look and smell of her shiny brown hair, liked the folding over and under of the three skeins of hair between my fingers. The braiding was also an act of anticipation—it came just before we crawled into her bed together and settled in among the pillows and sheets and I began to read and Sophie to listen.

Even this simple act of plaiting my child’s hair gives rise to questions about meaning. Why do more girl children wear their hair long in our culture than boy children? Why is hairstyle a sign of sexual difference? I have to admit that unless a boy child of mine had begged me for braids, I probably would have followed convention and kept his hair short, even though I think such rules are arbitrary and constricting. And finally, why would I have been mortified to send Sophie off to school with her tresses in high-flying, ratted knots?

All mammals have hair. Hair is not a body part so much as a lifeless extension of a body. Although the bulb of the follicle is alive, the hair shaft is dead and insensible, which allows for its multiple manipulations. We are the only mammals who braid, knot, powder, pile up, oil, spray, tease, perm, color, curl, straighten, augment, shave off, and clip our hair. The liminal status of hair is crucial to its meanings. It grows on the border between person and world. As Mary Douglas argued in Purity and Danger, substances that cross the body’s boundaries are signs of disorder and may easily become pollutants. Hair attached to our heads is one thing, but hair clogged in the shower drain after a shampoo is waste.

Hair protrudes from all over human skin except the soles of our feet and the palms of our hands. Contiguity plays a role in hair’s significance. Hair on a person’s head frames her or his face, and the face is the primary focus in most of our communicative dealings with others. We recognize people by their faces. We speak, listen, nod, and respond to a face, especially to eyes. Head hair and more intrusively beard hair exist at the periphery of these vital exchanges that begin immediately after birth, and once we become self-conscious, our concern that our hair is “in place,” “unmussed,” or “mussed in just the right way” has to do with its role as messenger to the other.

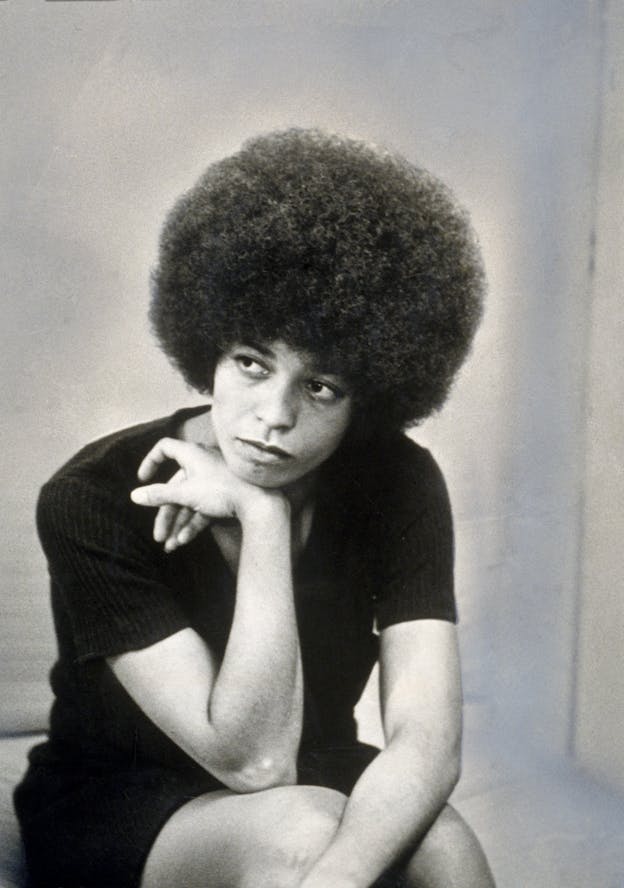

A never-combed head of hair may announce that its owner lives out side human society altogether—is a wild child, a hermit, or an insane person. It may also signify beliefs and political or cultural marginality. Think of the dreadlocks of Rastafarians or the long, matted hair of the sannyasis, ascetic wanderers in India. The combed-out Afro or “natural” for women and men in the 1960s communicated a wordless but potent political story. As a high school student, I thought of Angela Davis’s hair as a sign, not only of her politics, but of her formidable intellect, as if her association with Herbert Marcuse and the Frankfurt School could be divined in her commanding halo. Was the brilliant Davis a subliminal influence on my decision in the middle of the 1970s to apply a toxic permanent wave solution to my straight, shoulder-length blond hair, a chemical alteration that was literally hair- raising? The Afro style (sort of) on me—not just a white girl, but an extremely white girl—turned the “natural” into the “unnatural.” I was hardly alone in adopting the look. As fashions travel from one person or group to another, their significance mutates. Note the bleached blond hair of famous black sports stars or the penchant for cornrows among certain white people.

Despite its important role as speechless social messenger, hair is a part of the human body we can live without. Losing a head of hair or shaving our legs and underarms or waxing away pubic hair is not like losing an arm or a finger. “It will always grow back” is a phrase routinely used to comfort those who have suffered a bad haircut. Hair that touches a living head but is itself dead has an object-like quality no other body part has, except our fingernails and toenails. Hair is at once of “me” and an alien “it.” When I touch the hair of another person, I am similarly touching him or her, but not his or her internally felt body.

I remember that when my niece Juliette was a baby, she used to suck on her bottle twirling her mother’s long hair around her fingers as her eyes slowly opened and closed. It was a gesture of luxurious, soporific pleasure. Well after her bottle had been abandoned, she was unable to fall asleep without the ritual hair twiddling, which meant, of course, that the rest of my sister was forced to accompany those essential strands. Asti’s hair, as part of Juliette’s mother but not her mother’s body proper, became what D. W. Winnicott called a “transitional object,” the stuffed animal, bit of blanket, lullaby, or routine many children need to pave the way to sleep. The thing or act belongs to Winnicott’s “intermediate area of experience,” a between zone that is “outside the individual” but is not “the external world,” an object or ritual imbued with the child’s longings and fantasies that helps ease her separation from her mother. Hair as marginalia lends itself particularly well to this transitional role.

Every infant is social from birth, and without crucial interactions with an intimate caretaker, it will grow up to be severely disabled. Although the parts of the brain that control autonomic functions are quite mature at birth, emotional responses, language, and cognition develop through experience with others, and those experiences are physiologically coded in brain and body. The lullabies, head and hair stroking, rocking, cooing, playing, talk, and babble that take place between parent and baby during infancy are accompanied by synaptic brain connectivity unique to a particular individual. The cultural-social is not a category that hovers over the physical; it becomes the physical body itself. Human perception develops through a dynamic learning process, and when perceptual, cognitive, and motor skills are learned well enough, they become automatic and unconscious—part of implicit memory. It is when automatic perceptual patterns are interrupted by a novel experience, however, that we require full consciousness to reorder our expectation, be it about hair or anything else.

When Sophie went off to school with her two long, neat braids swinging behind her, she did not disturb anyone’s expectations, but when the psychologist Sandra Bem sent her four-year-old boy, Jeremy, off to nursery school wearing the barrettes he had requested she put in his hair, he was hounded by a boy in his class who kept insisting that “only girls wear barrettes.” Jeremy sensibly replied that barrettes don’t matter. He had a penis and testicles and this fact made him a boy, not a girl. His classmate, however, remained unconvinced, and in a moment of exasperation, Jeremy pulled down his pants to give proof of his boyhood. After a quick glance, his comrade said, “Everybody has a penis. Only girls wear barrettes.” Most boys in contemporary Western culture begin to resist objects, colors, and hairdos coded as feminine as soon as they have become certain of their sexual identity, around the age of three. Jeremy’s fellow pupil seems to have been muddled about penises and vulvas, but adamant about social convention. In this context, the barrette metamorphosed from innocuous hair implement to an object of gender subversion. The philosopher Judith Butler would call Jeremy’s barrette-wearing a kind of “performativity,” gender as doing, not being.

Girls have more leeway to explore masculine forms than boys. Unlike barrettes on a boy, short hair on a girl is not subject to ridicule, noteworthy because the “feminine” has far more polluting power for a boy in our culture than the “masculine” has for a girl. During three or four years before she reached puberty, another niece of mine, Ava, had a short haircut and was sometimes identified as a boy. One year she played with gender performance in the costume she chose for Halloween: half of her went as a girl, the other half as a boy. Hair was a vital element in this down-the-middle disguise. The long flowing locks of a wig adorned the girl half. Her own short hair served the boy half.

I began the fifth grade with long hair, but at some point in the middle of the year I chopped it into what was then called a pixie cut. When I returned to school newly shorn, I was informed that the boy I liked, a boy who had supposedly liked me back, had withdrawn his affection. It had been swept away and discarded at the hairdresser’s along with my silky locks. I recall thinking that my former admirer was a superficial twit, but perhaps he had succumbed to a Goldilocks fantasy. He would not be the last male personage in my life to fixate on feminine blondness and its myriad associations in our culture, including abstract qualities such as purity, innocence, stupidity, childishness, and sexual allure embodied by multiple figures—the goddesses Sif and Freya and the Valkyries of Norse mythology, the multitudes of fair maidens in fairy tales, numerous heroines in Victorian novels and melodramas, and cinematic bombshells, such as Harlow and Monroe (both of whom I love to watch onscreen). The infantile and dumb connotations of blond may explain why I have often dreamed of a buzz cut. The fairy-tale and mythological creatures so dear to me as a child may explain why I have had short hair as an adult but never that short and did not turn myself into a brunette or redhead. A part of me must hesitate to shear myself of all blond, feminine meanings, as if next to no hair would mean severing a connection to an earlier self.

Iris, the narrator of my first novel, The Blindfold, crops her hair during a period in her life of defensive transformation. She wanders around New York City after dark wearing a man’s suit. She gives herself the name of a sadistic boy in a German novel she has translated: Klaus.

The gap between what I was forced to acknowledge to the world— namely, that I was a woman—and what I dreamed inwardly didn’t bother me. By becoming Klaus at night I had effectively blurred my gender. The suit, my clipped head and unadorned face altered the world’s view of who I was, and I became someone else through its eyes. I even spoke differently as Klaus. I was less hesitant, used more slang, and favored colorful verbs.

My heroine’s butch haircut partakes of her second act of translation, from feminine Iris to masculine Klaus, a performance that belies the notion that appearance is purely superficial. By playing with her hair and clothes, she subverts cultural expectations that have shaped her in ways she finds demeaning.

Short hair or long? Interpretations of length change with time and place. The Merovingian kings (ca. 457–750) wore their hair long as a sign of their high status. Samson’s strength famously resided in his hair. The composer Franz Liszt’s shoulder-length hair became the object of frenzied, fetishistic female desire. The mini narratives of television commercials for formulas to cure male baldness reinforce the notion that the fluff above is linked to action below. Once a man’s hair has been miraculously restored, a seductive woman inevitably appears beside him on the screen to caress his newly sprouted locks. But then shampoo commercials for women also contain sexual messages that long, and sometimes short, frequently windblown tresses will enchant a dream man.

Because of its proximity to adult genitals, pubic hair is bound to have special meanings. Turkish women, for example, remove their pubic hair. In a paper on the meanings of hair in Turkey, the anthropologist Carol Delaney reported that during a visit to a public bath for a prenuptial ritual, the soon-to-be bride advised her to bathe before the other women so they would not see her “like a goat.” The expression moves us from the human to the bestial. Metaphor is the way the human mind travels. As George Lakoff and Mark Johnson argued in their landmark book Metaphors We Live By, “spatialization metaphors are rooted in physical and cultural experience.” Head hair is up on the body; pubic hair is down. Humans are superior to animals. Reason is a higher function; emotions are lower ones. Men are associated with the intellect—head—and women with passion—genitals. Hair above can be flaunted; hair below must be concealed and sometimes removed altogether.

Sigmund Freud’s brief interpretation of Medusa (1922) with her decapitated head, snaky mane, and petrifying gaze operates through a down-up movement. For Freud, the mythical Gorgon’s head represented a boy’s castration fears upon seeing “the female genitals, probably those of an adult, surrounded by hair, and essentially those of the mother.” The source of terror (the threatened penis) migrates upward and is turned into a maternal head with phallic serpents instead of hair. The horrible countenance makes the boy stiff with fear, a rigid state that nevertheless consoles him because it signifies an erection (my penis is still here). Indeed, Jeremy’s classmate, whose anatomical beliefs were predicated on the idea of a universal penis, might have been stunned by a girl with no feminine accoutrements, no barrettes, to signal girlness, and no penis to boot. Would the child have felt his own member was threatened by the revelation? There have been countless critiques of Freud’s brief sketch, as well as revisionist readings of the mythical Gorgon, including Hélène Cixous’s feminist manifesto: “The Laugh of the Medusa.”

What interests me here is the part of the story Freud suppresses. The mother’s vulva, surrounded by hair, is the external sign of a hidden origin, our first residence in utero, the place from which we were all expelled during the contractions of labor and birth. Isn’t this bit of anatomical news also startling for children? Phallic sexuality is clearly involved in the Medusa myth, and the snake as an image for male sexuality is hardly limited to the Western tradition. (In Taipei in 1975, I watched a man slice open a snake and drink its blood to enhance his potency.) The Medusa story exists in several versions, but it always includes intercourse—Poseidon’s dalliance with or rape of Medusa, and subsequent births. In Ovid, after Perseus beheads the Gorgon, her drops of blood give birth to Chrysaor, a young man, and Pegasus, the mythical winged horse. In other versions, the offspring emerge from the Gorgon’s neck. Either way, the myth includes a monstrous but fecund maternity.

Hair has and continues to have meanings, although whether there is any universal quality to them is a matter of debate. In his famous 1958 essay “Magical Hair,” the anthropologist Edmund Leach developed a cross-cultural formula: “Long hair = unrestrained sexuality; short hair or partially shaved head or tightly bound hair = restricted sexuality; closely shaved head = celibacy.” Leach was deeply influenced by Freud’s thoughts on phallic heads, although for him hair sometimes played an ejaculatory role as emanating semen. No doubt phallic significance has accumulated around hair in many cultures, but the persistent adoption of an exclusively male perspective (everybody has a penis) consistently fails to see meanings that are ambiguous, multilayered, and hermaphroditic, not either/or, but both-and.

One of the many tales I loved as a child and read to Sophie after our hair-braiding ritual was “Rapunzel.” The Grimm story has multiple sources, including the tenth-century Persian tale of Rudaba, from the epic poem Shannameh, in which the heroine offers the hero her long, dark tresses as a rope to climb (he refuses because he is afraid to hurt her), and the medieval legend of Saint Barbara, in which the pious girl is locked in a tower by her brutal father, a story that Christine de Pisan retells in The Book of the City of Ladies (1405), her great work written to protest misogyny. The later tales “Petrosinella” (1634) by Giambattista Basile and “Persinette” (1698) by Charlotte Rose de Caumont de la Force are much closer to the Grimm version (1812), which the brothers adopted from the German writer Friedrich Schultz (1790).

In all the last four versions of the tale, the action begins with a pregnant woman’s cravings for an edible plant (rampion, parsley, lettuce, or a kind of radish—rapunzel) that grows in a neighboring garden owned by a powerful woman (enchantress, sorceress, ogress, or witch). The husband steals the forbidden plant for his wife, is caught, and, to avoid punishment for his crime, promises his neighbor the unborn child. The enchantress keeps the girl locked in a high tower but comes and goes by climbing her captive’s long hair, which then becomes the vehicle for the prince’s clandestine entrance to the tower. The final Grimm version, cleansed for its young audience, does not include Rapunzel’s swelling belly or the birth of twins, but “Petrosinella” and “Persinette” do. When the enchantress realizes the girl is pregnant, she flies into a rage, chops off the offending hair, and uses it as a lure to trap the unsuspecting lover. The heroine and hero are separated, suffer and pine for each other, but are eventually reunited.

Rapunzel’s fantastical head of hair figures as an intermediate zone where both unions and separations are enacted. A pregnancy begins the story, after all, and the lifeline between mother and fetus is the umbilical cord, cut after birth. But an infant’s dependence on her mother does not end with this anatomical separation. Rapunzel’s hair or extensive braid is a vehicle by which the mother-witch figure comes and goes on her visits, an apt metaphor for the back-and-forth motion, presence and absence of the mother for the child that Freud famously elaborated in Beyond the Pleasure Principle when he described his one-and-a-half-year-old grandson playing with a spool and string. The little boy casts out his string, accompanied by a long “oooo,” which his mother interpreted as his attempt to say “fort,” gone, after which he reels it in and joyfully says “da,” there. The game is one of magically mastering the painful absence of the mother, and the string, which Freud does not talk about, serves as the sign or symbol of the relation: I am connected to you. Rapunzel’s hair, then, is a sign of evolving human passions, first for the mother, then for the grown-up love object and the phallic/vaginal fusion between lovers that returns us to the story’s beginning: a woman finds herself in the plural state of pregnancy.

The story’s form is circular, not linear, and its narrative excitement turns on violent cuts: the infant is forcibly removed from her mother at birth, then locked in a tower, cut off from others, and jealously guarded by the story’s second, postpartum maternal figure. After the punishing haircut, Rapunzel is not only estranged from her lover, she loses the sorceress mother. Notably, Charlotte Rose de Caumont de la Force reconciles the couple and the enchantress in “Persinette,” an ending that is not only satisfying but one that dramatizes the fact that this is a tale of familial struggles.

A child’s early sociopsychobiological bond with and dependence on her mother changes over time. Maternal love may be ferocious, ecstatic, covetous, and resistant to intruders, including the child’s father and later the offspring’s love objects, but if all goes well the mother accepts her child’s independence. She lets her go. Rapunzel’s long hair, which belongs to her, but which may be hacked off without injuring her, is the perfect metaphor for the transitional space in which the passionate and sometimes tortured connections and separations between mother and child happen. And it is in this same space of back-and-forth exchanges that a baby’s early babbling becomes first comprehensible speech and then narrative, a symbolic communicative form that links, weaves, and spins words into a structural whole with a beginning, a middle, and an end, one that can summon what used to be, what might be, or what could never be. Rapunzel’s supernaturally long cord of hair that yokes one person to another may be assigned yet another metaphorical meaning—it is a trope for the telling of the fairy tale itself.

My daughter is grown up. I remember combing and braiding her hair, and I remember reading her stories, stories that still live between us, stories that used to soothe her into sleep.

This essay appears in the forthcoming collection Me, My Hair, and I: Twenty-seven Women Untangle an Obsession, edited Elizabeth Benedict and published by Algonquin Books.