With Francis now on their side, climate-change activists and scientists have higher hopes that they can save the world. Scientists Michael Mann and Veerabhadran Ramanathan both described the Pope's environmental encyclical, Laudato Si, as a “game-changer” when it was published published in June. ThinkProgress’ Joe Romm went further, likening Pope Francis to Winston Churchill on the eve of World War II.

There's no question that the religious leader of 1.2 billion people is as powerful a spokesman as the climate movement could hope for. However, the real-life “Francis Effect”—as the media has dubbed it—hardly matches the hype. There’s little evidence that his message is reaching anyone who didn’t already believe that climate change is a problem. When it comes to climate, it seems, partisanship and ideology are more powerful forces than faith. The Pope can only sway those who are willing to listen to him on political issues, and American conservatives, by and large, are not.

Catholic politicians who disagree with the Pope have already dismissed his climate message. "America is not a planet,” Marco Rubio remarked at last week’s GOP debate, suggesting that's reason alone not to bother cutting emissions. Asked yesterday on This Week about Pope Francis' visit, Rubio said that he has "no problem with the Pope," but said he doesn't have to take cues from him on economic or climate issues the way he does on "essential" social issues like the santity of life. "The pope, as an individual, an important figure in the world, also has political opinions," Rubio said. "And those, of course, we are free to disagree with. He obviously opines about his views of the church's role or the—what we should be doing with the climate or things of this nature, on the economics." Earlier this summer, on the week the encyclical was published, Jeb Bush took an identical stance, insisting, “I don’t get economic policy from my bishops or my cardinals or my Pope.” Republican Congressman Paul Gosar of Arizona took his opposition to another extreme last week, writing in an op-ed for Townhall that he plans on boycotting the Pope's address to Congress on Thursday. "If the Pope wants to devote his life to fighting climate change, then he can do so in his personal time,” Gosar fumed. “But to promote questionable science as Catholic dogma is ridiculous."

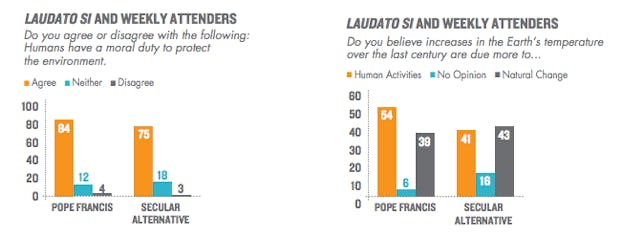

The Pope’s message may be falling on deaf ears among conservative Catholic politicians. But what about everyday Catholics? A survey from Faith in Public Life tested the Francis Effect by having some participants read a news story about the encyclical, and others a generic story with a similar call for action:

Catholic Republicans who read about Laudato Si were more likely to agree that human activities are responsible for climate change (37%) than those who received the alternative message (27%), and to agree that humans have a moral duty to protect the environment (77%) than those who read the story featuring generic climate experts (70%).

According to these results, the Francis Effect is modest, if mildly beneficial. But David Roberts of Vox noted an important disclaimer: There was virtually no difference between the groups when it came to agreeing that the U.S. government must act (affirmative answers hovered around 30 percent).

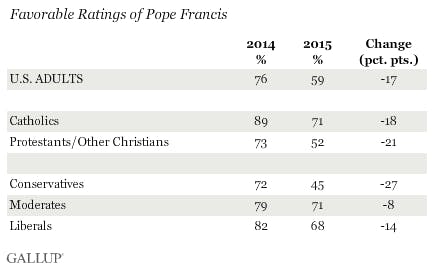

The best explanation for the Pope's relative lack of influence on Americans' views on climate change was identified by Gallup in early July. The polling firm found that public opinion of Pope Francis has dropped by 17 percent overall, and by 18 percent among Catholics, from 2014 to 2015. The group that has lost the most faith in the Pope, not surprisingly, is conservatives: Where 72 percent held a favorable opinion of him in 2014, the number plunged to 45 percent in 2015. The Pope's emphasis on climate change is one explanation for this drop, but not the only one. Francis’ sharp condemnation of capitalism as a driver of inequality surely plays a major role as well. His encylical ties the issues together, declaring that the “idea of infinite or unlimited growth, which proves so attractive to economists, financiers and experts in technology ... is based on the lie that there is an infinite supply of the earth's goods, and this leads to the planet being squeezed dry at every limit." Catholic Republicans may hear this message and simply tune it out.

The Pope's trip could, in fact, have the unintended consequence of casting him as a more polarizing and partisan figure, and end up closing even more conservatives' minds. The unprecededented attention that will be called to his messages about climate and capitalism—and about America's responsibilities to the poorer nations—may provide some much-needed momentum for direct environmental action, but it could also harden the conservative view that this pope has all the wrong political allies. Environmental groups, excited to have a pope on their side, have piggybacked on his visit to promote an array of their Pope-friendly causes. The Moral Action on Climate Network and the Earth Day Network Environmentalists expect up to 200,000 to attend a climate justice rally on Thursday, the same day Francis speaks to Congress. The problem is, when it comes to mobilizing U.S. and global action to slash greenhouse gas emissions and help the poor and vulnerable to adapt, the attendees at this rally matter the least; they're the ones who already agree with what the Pope has to say.

Even if the Pope's capacity to reach conservative skeptics is limited, it would be a mistake to completely write off the positive ripple effects that his climate focus may have on the environmental movement. This week's visit ensures that more American Catholics are tuning into the Bishop of Rome's appeal to climate action, and the Vatican's outreach to America could conceivably influence some Catholics who are only vaguely concerned about climate change to take more direct action. It’s possible, too, that the Vatican’s condemnation of fossil fuels hurting the poor will give additional fuel to divestment campaigners at Catholic universities. It’s surely going to force several of the Catholics running for president to answer some awkward questions about their faith conflicting with their views on climate change.

Any change the Pope can bring to our climate politics will be less tangible and harder to measure than, say, President Barack Obama's executive orders. The Pope can't overhaul the global economy or the energy grid, or get world leaders on the same page. (And he hasn't offered to divest from fossil fuel stocks, which is one concrete action he could take). The Pope is providing something undeniably powerful to the climate debate by framing the moral argument for why people of faith should care more about this global crisis. But the chief Francis Effect on climate, at best, will be a long-term shift in public opinion. And by the time the effects of that shift finally start to take hold, and public opinion turns into demands for action, it will already be too little, too late, to realistically slow global warning.