Neither Rick Santorum nor Senator Lindsey Graham is likely to win the Republican nomination for president, much less the presidency itself. But their back-and-forth at Wednesday undercard debate illustrated, better than any other exchange of the night, why immigration is such a divisive, and potentially decisive, issue for the Republicans. Graham won applause from the establishment-friendly crowd by calling for Republicans to reach out to Hispanic voters, but in the end, the toxic blend of faux-populism and xenophobia that Santorum championed is the dominant strain in the GOP primary.

The GOP’s autopsy of its 2012 election loss laid out “how precarious our position has become” vis-a-vis the Hispanic community. Mitt Romney had performed dismally among Hispanics voters, famously suggesting that America’s 11 million undocumented immigrants self-deport, and those voters comprise an increasingly important bloc in swing states like Ohio, Colorado, New Mexico, Virginia, and Florida. The report, which came short of advancing policy solutions, suggested that Republicans reverse this trend by being more “inclusive and welcoming” to Hispanics. George W. Bush secured 44 percent of the Latino vote in 2000 by preaching a compassionate brand of conservatism, the report claimed. Any candidate hoping to seize back the White House in 2016 needed to do likewise.

Graham made this same point Wednesday. Bush “won with Hispanics,” he said (abeit inaccurately), and chastised Santorum and others for supporting politically unfeasible, unpopular hardline proposals like mass deportation.

“What we need to do,” Santorum responded, “is we need to win—we need to win fighting for Americans. We need to win fighting for Americans in this country.”

“Hispanics,” said Graham, cutting in, “are Americans.” In the 2016 Republican primary race, this has become an assertion worthy of the applause it received.

Graham is hardly liberal on immigration: For one, he favors ending birthright citizenship. His grievance with Santorum stems solely from the practical difficulties and political inexpediency of deportation on such a bold scale. That is, he's one of the few prominent Republicans to put the message of the 2013 GOP report into practice. In the aftermath of President Barack Obama’s re-election, he worked with Senator Marco Rubio and Senate Democrats on a comprehensive immigration bill to establish a pathway to citizenship for undocumented immigrants. Faced with intense backlash from conservatives like Senator Ted Cruz, who joined Santorum on Wednesday night in referring to the plan as “amnesty,” Rubio went on to oppose his own bill. Two years later, with an ongoing debate over how best to do away with the Fourteenth Amendment, and Mitt Romney’s self-deportation proposal seems downright friendly.

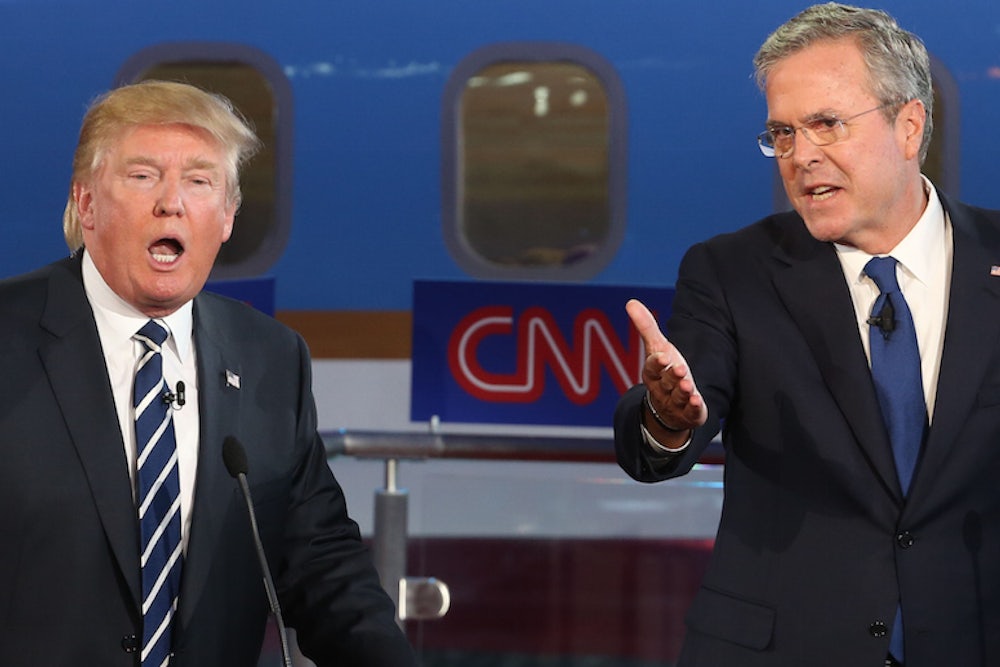

Later Wednesday, on the main debate stage, the closest anyone came to challenging the hardline anti-immigration stance was Chris Christie, who, like Graham, took care not to object to the principle. Instead, Christie said only that the identification, tracking, and forced removal of 11 million individuals from the United States is “an undertaking that almost none of us could accomplish given the current levels of funding, and the current number of law enforcement officers.” Ben Carson, another deportation skeptic, clarified that he “would be willing to listen” to anyone who could explain “exactly how” such a purge would be accomplished. In over five hours of debate Wednesday, the only candidate to express a moral opposition to mass deportation was Jeb Bush, who said it would “destroy community life” and “tear families apart”—but only after lamenting the “hundreds of billions of dollars” it would cost. Bush also defended his bilingualism and his wife’s Mexican heritage, which Donald Trump has suggested is influencing Bush's "soft" immigration position, but he did it so tepidly as to merely raise further doubts about his ability to challenge the real-estate magnate, on immigration or anything else.

Jeb: Apologize to my wife Trump: No Jeb: Well alright then, thanks so much for your time

—

ebruenig

What we are seeing now is more than just the usual dash to the right in the Republican primary. It is the end stages of a long fight for the soul of the party itself, the “tug of war,” as New Republic’s Brian Beutler has written, “between its own ego and its conservative id.” It may be tempting to dismiss Trump’s fearmongering (“They’re bringing drugs. They’re bringing crime. They’re rapists.”) or Bobby Jindal’s fascism (“immigration without assimilation is invasion”) as outlandish and politically untenable, but Santorum’s appeal to the anxieties of “workers” is in keeping with a demonstrated decades-long migration of white lower and lower-middle class voters to the Republican Party. Taken together, they are articulating a coherent strategy to win back political power, one predicated on the supposed threat that immigration poses to the security, cultural purity, and economic stability of white America.

Republican elites believe that they can stave off this racialized fissure with bilingual campaign ads and half-hearted appeals to pragmatism. What they ignore is not simply the extent to which they themselves have deliberately encouraged the accommodation of white supremacy within their ranks, but the likelihood that those elements actually have a more coherent vision for the future than they do. Latinos are not a one-issue monolith. Polling shows their views on key issues such as climate change, social welfare, and the minimum wage are out of line with GOP policy. Whites, meanwhile, still make up over 70 percent of voters. It's entirely possible, likely even, that scaring enough white voters away from the Democrats to win a general election represents a more manageable task than moderating the Republican Party on almost every major issue. So while Santorum stands no better chance of becoming the next president than Graham does, his strategy of pitting working class whites against immigrants at least has the prospect of electoral success. Consciously or not, the Republican Party has decided to put it to the test.