The first time Jennifer Boyd met Dr. Ben Carson, he was operating on her 10-year-old niece. The next time, he was operating on her husband James. Last night, at a small Carson debate-watching party in south Maryland, she recalled how the doctor showed his concern in the smallest of ways. “He was worried that I hadn’t had breakfast,” says Boyd, recalling the day of her husband’s surgery. Every time she’s met Carson, she adds, “the good just comes out.”

It was just minutes before the second Republican debate was about to start, and there was only a handful of people at the Carson watch party in the back of La Plata’s Green Turtle bar, about an hour outside of Washington, D.C. “More people are coming,” promised Boyd, who organized the event. Only a few more showed up, but they, too, brought their own stories of Carson’s goodness. Renee Morris made sure that her children read Carson’s books when they were growing up, to learn about his dramatic rise from poverty to become of the country’s most prominent neurosurgeons. To this day, he’s been a personal force in her life. “I’m 48, and he’s inspired me to go back to school to get my nursing degree,” said Morris, who works as insurance agent and home health aide.

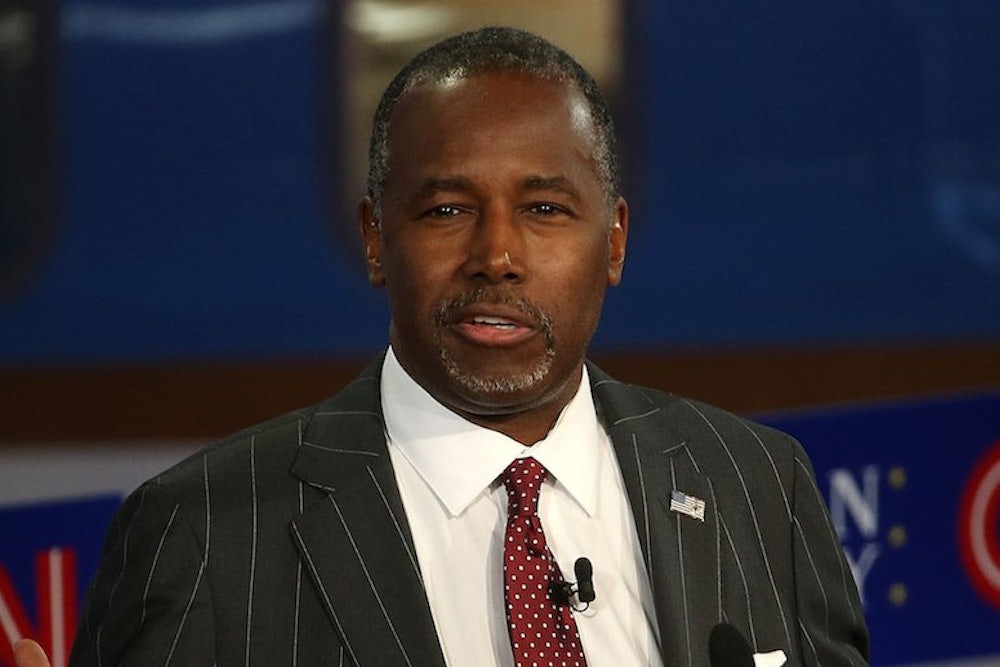

This is the version of Carson—renowned surgeon, role model, humanitarian—that long preceded his sudden rise to political stardom in 2013 when he confronted President Obama at the National Prayer Breakfast. And it’s been the key to his seemingly inexplicable rise in the polls since the first Republican debate last month. For the many voters attracted this year to outsider, “non-politician” candidates, Carson represents something decidedly different from Donald Trump: an outside force for virtue and good, a man who will heal the nation by dint of his character.

As his fans describe it, Carson is basically the Superego to Trump’s Id. “The more people get to know him—that’s all it’s going to take,” Boyd said. “He makes you feel reassured. He’s the only one who can bring this country together.”

The watch party itself was a small snapshot of unity: half white and half African-American, roughly representative of the surrounding Charles County. Like Carson’s own stage presence, the gathering was fairly subdued at the start: heavy on the dinner orders, light on the booze. Everyone remained seated. But once the fireworks began, the volume rose—and the crowd had mixed reactions to Carson’s place in the conversation. Was the man they admire for his quiet dignity being too quiet?

Carson remained subdued throughout the night, declining to attack his opponents despite being prompted by CNN’s moderators on multiple occasions. “He didn’t take the bait,” one of the debate-watchers told me approvingly after Carson rebuffed a question asking which of his opponents was “politically expedient.” But when he went head to head with Trump, his fans didn’t hold back from throwing some of the elbows that Carson wouldn’t.

“That’s nonsensical speech!” said James Boyd, when Trump reaffirmed his position that there might be a connection between autism and vaccines. “He’s demonstrating total ignorance at this point.” Boyd, who is a doctor of internal medicine, went on to explain to the other Carson supporters that new diagnostic criteria—not vaccines—were helping to drive the rise in autism. But when Carson himself responded, he refused to attack Trump—and in fact affirmed some of what Trump said. There’s a large body of evidence that “there’s no autism associated with vaccinations,” Carson said. But he added that it’s true “that we are probably giving way too many in far too short a time”—lending a voice to the so-called vaccine-delayer movement that’s also medically dubious. One supporter piped up that Carson was in fact partly agreeing with what Trump had to say on vaccines, effectively letting him off the hook. But the others in the group didn’t seem to hear her, as they were still picking apart Trump’s misguided statement.

It wasn’t the first time that the room had piled on Trump. Remarks from the billionaire that had previously been a cathartic shock to the system, it seemed, were beginning to sound more repetitious and unsatisfying. When Trump was asked how he would get the Russians out of Syria at one point, he gave the usual reply: His personal charisma would do it. “You didn’t answer the question!” exclaimed Renee Morris’s husband William.

One debate-watcher, Darryl Johnson, told me he’d been an enthusiastic Trump supporter until recently. “When he started talking about the border, that blew me away,” said Johnson, a mattress and carpet salesman. But even before the debate, Johnson said he'd come to feel like Trump’s speeches had all started to sound similar; he turned off the TV rather than finish watching his remarks this week in Dallas. “He’s real big on himself—I was looking for something of substance,” he said.

Trump didn’t win Johnson back in the second debate, either. It was the first time that Johnson had heard about Trump criticizing Jeb Bush’s wife (“If my wife were from Mexico, I think I would have a soft spot for people from Mexico.”) Johnson found that attack out of bounds, and he didn’t like Trump’s refusal to apologize, either. “Leave his family out of it—all the personal attacks,” he said. But Johnson had already come to the watch party prepared to make the leap to Carson, and he affirmed his conversion by the end of the night. It wasn’t anything in particular that Carson had said—just the man himself. “I like his intelligence, his demeanor, his cool,” Johnson said.

Paradoxically, the very things that drew these folks to Carson also made him less prominent on the debate stage—and, some feared, could limit his potential for continuing his rise in the polls. While Carson has benefitted from voters tired of Trump’s bluster—with his support rising especially from white evangelicals after a similarly low-key, almost sleepy performance in the first debate—it’s unclear whether Carson will simply be a rest stop on the way to a feistier candidate.

Throughout the night, there was a sense of muted disappointment that Carson didn’t get more chances to speak. Maybe, some argued, it was a good thing. “His character is shining through—he shines more because of all these people fighting back and forth,” said Renee Williams. “Everyone on stage is interrupting,” added her husband William. “When Carson speaks, he has something to say.”

But others wished he'd done more to play himself up. To really compete for the nomination, they said, it won’t be enough for him to be a symbol of virtue; he has to come across as a force for good. And that, they said, takes some forcefulness. “His biggest asset is his ability to bring people together,” said Boyd. “He needs to talk about that.”