For many women writers, doling out their stories has proved a successful path to a career in writing. In the past decade, a vast online space—websites like Thought Catalog, Rookie, and xoJane—has opened up for women to write about their early confrontations with adulthood, preferably with emphasis on their growth from awkward girls to complicated, yet desirable, women. Writing about “the Internet’s bottomless appetite for harrowing personal essays,” Slate senior editor Laura Bennett argues that the internet’s appetite for confessional writing points many young writers inward—not necessarily because they have something pressing to say but because, for women in particular, a pitch based on a traumatic personal experience is a reliable way to get an editor’s attention.

Others argue that confessional writing is a radical act, providing a template for women to be their own subjects. But the troubling paradox is that, in their quest to spin a narrative out of the fabric of their lives, these writers often fall back on the same objectifying impulse of male writers and artists since time immemorial. In 1972, the art critic John Berger wrote, “men act and women appear. Men look at women. Women watch themselves being looked at.” Berger was writing about the depiction of women in classic oil paintings, but in so much personal writing today, young women fall into this same trap. Writers like Aspen Matis, the young author of the memoir Girl in the Woods, or Lily Brooks-Dalton, who recently published her first book, Motorcycles I’ve Loved end up—or, rather, start out by—commodifying their own womanhood.

In a spate of memoirs published in recent years by women in their twenties, the authors are their own subjects. Yet Matis’s disappointing memoir resembles a classic makeover story. In Girl in the Woods, she sets up a narrative of catastrophe and salvation. On her second night at college, Matis is raped in her dorm room by a boy she’s only met that night. Shaken, she drops out after her freshman year and hikes the Pacific Crest Trail. By the end, she has shed her “post-rape fat,” traded in glasses for contact lenses, changed her first name, and gotten hitched.

“I was ugly, had bad posture and thick glasses. I was chubby, my curly hair a mess, I felt unattractive, I always had,” Matis writes near the beginning of Girl in the Woods. “I was unseen. I had always been unseen.” Later, Matis is pleased to report that she feels beautiful for herself, not for any man. A quarter century after Laura Mulvey famously coined the term “male gaze,” we’re working on getting rid of the “male,” but that “gaze” is still all-important.

The emphasis on visibility, on being seen, is not unique to Matis. In Motorcycles I’ve Loved, Brooks-Dalton finds herself frustrated by men who belittle her, call her “cute,” and question her biking credentials. A petite woman, she “could never quite reconcile this discrepancy between who I wanted to be and who I appeared to be…People looked at me a little differently when I arrived in leather, on two wheels, and it made me begin to look at myself differently, too.”

Alida Nugent’s Don’t Worry, It Gets Worse: One Twentysomething’s (Mostly Failed) Attempts at Adulthood, her first book, is a humorous—and self-deprecating—jaunt through the author’s post-college years as a blogger in New York City. Much of the book centers on her eating habits: “I am suck-your-stomach-in-Barbie,” she quips. In one chapter titled “The Grilled Cheese That Changed My Life,” Nugent writes about her gradual acknowledgment that it’s ok to enjoy food. In writing about food, Nugent toggles between her feelings of shame and wild abandon. But when she gives into the pleasure of eating, she insists, “There’s nothing sexier than a woman eating a sandwich.”

In Andie Mitchell’s debut memoir, It Was Me All Along, being seen is more explicitly front-and-center: The book is about her lifelong struggle with her weight. When a cute guy asks her to the prom, Mitchell has finally gotten “exactly what I’d wanted. To be seen. To be seen as beautiful.”

Our culture loves to gawk at the ugly side of women—to peer at stars without their makeup and publish their un-Photoshopped images, to put women’s looks under a microscope until every blemish surfaces. It’s not surprising that so many women writers respond to this scrutiny by taking ownership of their own looks. And yet there’s a strange self-consciousness to these very polished and often engaging narratives, a desire to look good while looking bad that is unsettling. Taken together, these memoirs suggest that to be a woman is first and foremost, in Berger’s words, to be “an object of vision: a sight.”

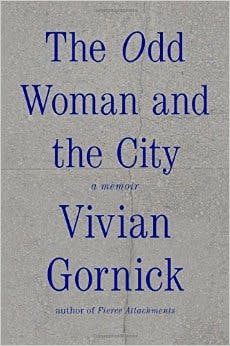

After I finished reading these books, I opened Vivian Gornick’s latest memoir, The Odd Woman and the City. Reading Gornick—who published her first memoir, Fierce Attachments, at the age of 52—on the heels of these memoirs was like dipping my feet into a cool, clear lake after walking barefoot on hot pavement. Gornick’s prose is tight, taut, shot through with a dynamic, youthful energy that belies her 80 years. The comparison to these twentysomething first-timers is completely unfair, of course. But Gornick’s subject mirrors that of her younger counterparts: the search for the self, the quest for a fulfilling and independent life.

Despite the thousands of words Gornick has spilled on the subject of herself, the point of her memoirs is not to reveal this self to the world. As she writes in her book The Situation and the Story, “I become interested … in my own existence only as a means of penetrating the situation in hand.” Or, as she put it in an interview last year with The Believer, “The story is everything.”

As women, we confront ourselves as objects to be seen practically from the moment of birth. Perhaps it’s a radical inversion to flip the lens and gaze into our own faces, our own bodies, our own minds. But, for me at least, that impulse is depressing. It makes these young authors seem not like writers with ideas to share but things to be hawked. It speaks to a culture that sees young women as valuable primarily when the product they’re selling isn’t an idea or an argument or even a story but the most intimate, and often humiliated, version of themselves.