There have been only occasional efforts to translate Martin Amis’s novels to the screen: his 1975 novel Dead Babies became the fairly dismal Mood Swingers in 2001, and Money, the much-admired “suicide note” of John Self, became a two-part TV movie several years ago under the aegis of the BBC. But as source material Amis’s fiction has proven somewhat elusive. Following in the literary tradition of Nabokov and Henry James, the appeal of his novels lies with their linguistic inventiveness rather than compelling plots. Their greatness as literature seems to promise dividends on screen. Then you see the films—and suddenly adapting Amis doesn’t look like a very good idea.

Here, nevertheless, is London Fields, a new adaptation of Amis’s best-known book, making its world premiere this Friday at the Toronto International Film Festival in Canada. And the shocking thing about this adaptation is that it’s not bad. Indeed, as literary adaptations go it’s quite good. Lead by first-time director Mathew Cullen, and co-written and co-produced by Roberta Hanley, the film stars Billy Bob Thornton, Jim Sturgess, Theo James, Amber Heard, and, most oddly, Johnny Depp. Admirers of the novel will be pleased to learn that the film is about as faithful to the original text as an adaptation of its scale could hope to be.

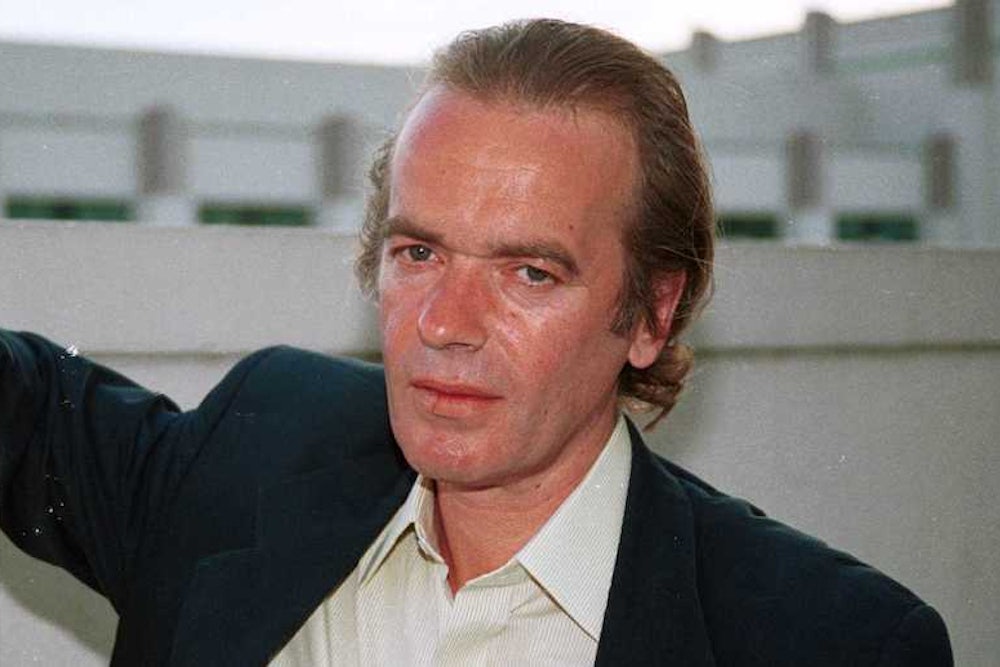

I reached Martin Amis by phone at his home in New York before the premiere of the film this week. In the long and wide-ranging conversation that followed we discussed the adaptation, the differences between literature and cinema, and the state of the novel in 2015.

Calum Marsh: There’s a certain kind of prose stylist whose work was rarely adapted. There are very few Updike movies, for example. Not a lot of Roth films. I don’t think there are any Bellow films…

Martin Amis: No, well, Jack Nicholson was going to make Henderson the Rain King. And I was involved for a little bit in trying to make a film of Humboldt's Gift. It’s true. The more the prose occupies center stage in a novel, that’s something you almost have to get rid of before you get to stage two.

CM: Do you think that’s why the worse the prose in a novel the better the film it will yield?

MA: I think that’s not a bad general rule. Sometimes it happens that you take a very undistinguished piece of prose—like The Godfather for instance, which is a marvelous story but not a marvelous tour de force of writing. But when you have someone like Coppola making the film, then it’s as if Mario Puzo’s prose is being rewritten by Nabokov, just on the strength of the cinematography. It beautifies things that on the page were made quite inert.

CM: In the case of something like The Godfather, it’s as if Coppola brings to bear on the material a film style that would be the equivalent of good prose.

MA: Of genius prose. And it sort of makes you realize how relatively easy it is to make things look ravishing on the screen. Much harder, evidently, on the page.

CM: When you write a novel does you ever think about how well it will lend itself to a film?

MA: It’s something that you think about after a long day’s work and a few drinks. Then you might think about it. But it’s absolutely not at all what’s bothering you when you’re actually writing. The novelist is spoiled. And is so unused to any kind of collaborative work. The novel par excellence is the product of one mind—there’s not even a suggestion from anyone else. Granted the movies constitute a director’s medium, the director is utterly dependent on—as Sidney Lumet said when I interviewed him—dependent on the weather. If you’re writing a novel, you are the weather. You are the crowd scene. You are the sunset. You are everything. That freedom never presents itself to the filmmaker.

CM: I wonder if that’s becoming less true with digital effects. You can whip up a storm if you’d like to.

MA: I can’t, but they can. But no that’s true. And it will get more like playful, and much less dependent on nuts and bolts and budget.

CM: The novel, too, collaborates with the reader imaginatively. For instance, if you write, “She was the most beautiful woman in the world,” or “She painted the most beautiful painting in the world,” the reader knows now that it’s the most beautiful thing. But if you see a film and they show you what they mean to be the most beautiful woman, you might watch the film and think, I don’t think she’s really that beautiful.

MA: In that sense, curiously, film is much more literal. Much more literal-minded than a novel. Because it’s as if the analogy would be a film where the audience has its eyes shut and is imagining the action. That’s more like what a reader is doing. They have their eyes open to read the words but their eyes are shut imaginatively. They’re not literally coming up with the most beautiful woman on earth or the most beautiful painting. That’s all left to the imaginative collaboration of the reader. The reader is almost as much of an artist as the writer, in that it’s they who fill in the visual images. I’m sure every reader has a different image of Elizabeth Bennet in Pride and Prejudice or Mr. Darcy, with different pointers by the author. But every individual will suit it to their own fancy.

CM: It’s a cliche to say that an adaptation of a book doesn’t look like you imagined it would. Seeing Nicola as a blonde in the film was shocking to me in a similar way.

MA: Yes, I mean, I always thought it was pretty fundamental that she was dark and devilish. But I must admit that very soon ceased to concern me when I was watching the film because Amber Heard is so commanding.

CM: Absolutely. I was more distracted by Keith. He seems more severe than he reads. Less buoyant.

MA: Yes, except that charming scene where he dances in the rain. Which isn’t, again, something you can imagine the Keith on the page doing, because he’s so sort of clumsy and graceless, and Jim Sturgess is not. But you accept that difference and it’s a different way of expression an aspect of him. But no, he’s too attractive, as well, for Keith, in my view. But he does it in a special way.

CM: I think the one novel of yours I couldn’t imagine as a film at all is Other People.

MA: I would advise anyone strongly not to go near that. Uncertainty about what’s actually going on, I think, is just about sustainable for a novel for a few pages, but it’s very vexing in a film. I don’t think you can build up the kind of trust on-screen that you just about can on the page.

CM: An invigorating sentence can sustain you on its own merits, even if the information it imparts isn’t gripping. In a film you need that momentum all the time.

MA: The arrow of development is much sharper in film. But I would say that in the last couple of generations, even the literary novel has become much more one-directional than it used to be, towards development and plot-driven, simply as a response to what’s called the acceleration of history—when the rate of history and historical development has speeded up. Writers certainly have responded to that.

CM: You’ve said before that you don’t read living writers.

MA: I don’t read younger writers. I read people who’ve had time to endure a bit. The trouble with a brilliant novel by a twenty-eight year old is that it’s only lasted six months. It seems to be an uneconomical way of organizing your reading. Better to read stuff that’s likely to have withstood the time for a few decades at least.

CM: I might read a novel by a twenty year old to keep with the cultural conversation. Something to contribute at the dinner party.

MA: Yeah, but I’m not interested in just sort of keeping up with anything. Nor in the kind of novelist who thinks it’s their duty to interpret the latest technological or social media development. I like a step back further from things.

CM: I think it was Updike who said that younger writers see the world with fresh eyes until you age out of it. Do you not feel tempted to catch a glimpse of what’s happening on the fore?

MA: I think you get less equipped to do that as you get older. You get less interested in the short term developments. I just think that’s only natural, that you should feel that way—you get that out of the way when you’re young. Your distance increases and you become interested in other kinds of things.

CM: You develop a deeper connection to history?

MA: Yeah, that. My father said there comes a point where it’s as if someone says to the novelist, “it isn’t like that anymore, it’s like this.” Just by getting older you close yourself off to what “this” is. But in my view it’s better not to try—in fact you’re not tempted to try, because that ceases to interest you.

CM: Changes in trend aren’t reserved just for what’s being written, either, but how things are received. Who is in fashion? What kind of literature is in fashion? The conversation today often revolves around politics in a pronounced way. Political correctness seems to loom over everything.

MA: It does at the moment. You’re right, in that pressure builds up for you to pass various tests to be considered alright in this respect and in that. But half the time what’s being invoked is not a literary value or a literary concept at all. It’s a social concept, a social value. That’s all very well, socially. But for instance, the feminist and the politically correct—what will they make of King Lear? It has some ferociously misogynistic passages. You have to tick Shakespeare off for not being right on in 1595. As you say, it’s to do with fluctuations to do with fashion and politics. If it does succeed in changing literature, then it’ll be obviously for the worse. I think we can trust writers who have anything in them to not be menaced and intimidated by that.

CM: I agree. But I feel like that bar of what passes the test, what’s acceptable socially, keeps getting higher and higher. You knock Shakespeare off the list — it’s no good now. You wrote about it happening to Larkin after his death. His biographer seemed annoyed that he doesn’t seem to have any interest in wanting to change.

MA: He didn’t want to develop and to grow. Well, yeah, I think that’s just anachronistic. It shows a lack of historical imagination. It’s brutally uninteresting compared to what was actually being lived by Larkin. The forces playing on him in Hull in 1960 are not going to be what bothers someone in London in 2015. But that’s among all the stuff that will tend to be lost as long as these socio-political standards are applied to literature where they have no business, in my view.