If you imagine a scenario in which Donald Trump vanishes from the Republican presidential race, and isn’t replaced by an equally brash panderer—that is, where his supporters scatter to a variety of other second-choice candidates—then you can make the case that behind all the dirt Trump has kicked up, the Republican presidential field is basically healthy.

Conservative Bloomberg View columnist Ramesh Ponnuru flirted with that argument at the end of August, by listing all the reasons Trump is unlikely to win the primaries, including the fact that “Republican elected officials would consolidate behind a consensus choice if Trump started winning delegates.”

If the central thematic question of the first debate was whether the candidates and Fox News itself could puncture Trump’s bubble, this time it’s whether any of those potential consensus candidates can distinguish themselves and climb out of the doldrums where they’ve been stuck for weeks. Ponnuru’s remains the best argument against full-blown panic on the right, but three weeks later it’s faring worse than it was, for a number of reasons.

1) Trump’s rise has continued unabated.

2) The four candidates with the most establishment-friendly backgrounds and campaigns—Jeb Bush, Marco Rubio, John Kasich, and Scott Walker—have stagnated, fallen, or, in Walker’s case, collapsed.

3) To the extent that anyone has benefitted from this poor showing, it isn’t another Republican elected official, but Dr. Ben Carson, a candidate with religious bona fides, radical politics, and an anti-elite bent.

In several recent polls Trump and Carson control more than half the vote between the two of them, while Ted Cruz, who’s fishing from the same electoral ponds, outpolls most or all of the above, putatively electable candidates.

Those four establishmentarian candidates are in the grip of a severe collective action problem. Were one of them the consensus choice of the GOP donor class, the current field would look a lot like the one in 2012, with Carson in the role of a flash in the pan candidate like Newt Gingrich or Herman Cain. Trump would be the key difference between the two fields, but with Rubio or Kasich holding steady at 20 percent, in a field clear of other establishmentarian candidates, he could safely be considered, in Ponnuru’s words, a nuisance, not a nightmare.

Mitt Romney didn’t have a particularly smooth path to the nomination in 2012, but as other candidates bowed out, his share of the vote grew and grew. He never polled nearly as poorly as any of his heirs apparent, who are doing to themselves what so often kills conservative candidates—dividing their natural supporters. This leaves those up-for-grabs Republicans no obvious place to register support, because no candidate seems to have a greater chance to win than any other.

Back in August, after Rick Perry’s floundering campaign stopped paying its staff, his national co-chairman—a prominent Iowa Republican named Sam Clovis—needed a place to go. Were Scott Walker still leading in Iowa, as he was until mid-July, or were some other viable Republican polling near 20 percent, as Walker was, Clovis could have joined another traditional Republican campaign. Instead, he landed with Trump. Perry had been Trump’s fiercest critic.

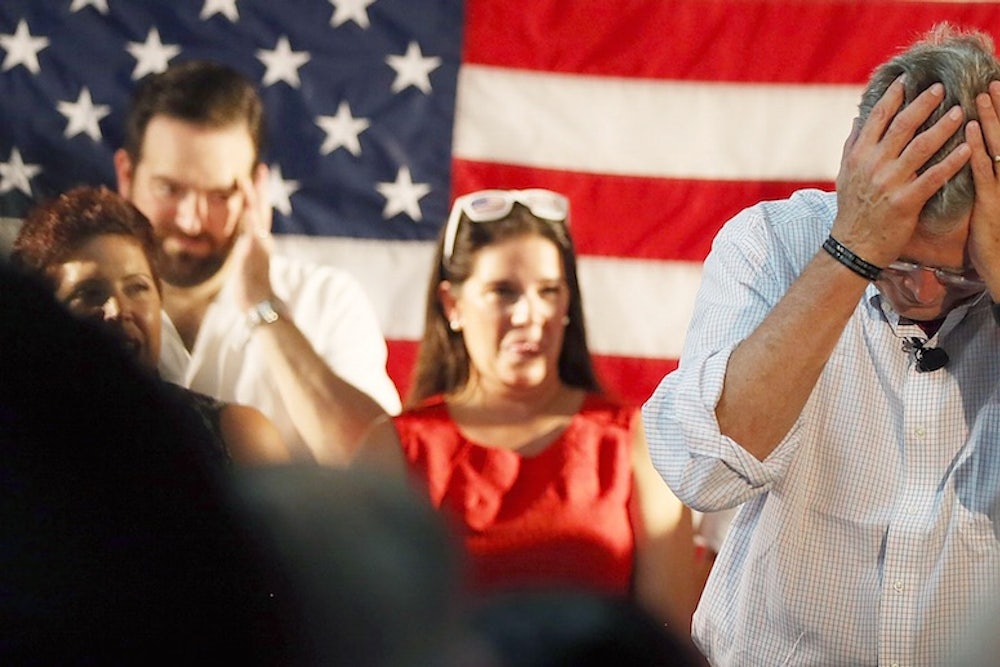

For the purposes of the debate, ameliorating the collective-action problem would entail one of the four establishmentarian candidates performing unusually well, and at the expense of the others. That could mean making the case, implicitly or explicitly, that the key to defeating Trump isn’t taking him head on, but winnowing the rest of the field to create a single power center of opposition to him. It could also mean simply putting in a memorable performance. But if the debate ends, and the same four candidates are tussling among themselves for the same small sliver of the conservative electorate, then maybe it'll be time for Republicans to panic after all.