Politics and advertising are closely intertwined. Like a good advertisement, a good politician needs to present a compelling case for why the voter should check his or her box on the ballot over all the other options.

Many good ads or politicians will make a direct appeal to viewers' emotions—and of all the candidates in recent memory, Donald Trump may be the best at doing this.

While some pundits and late-night comedians have eviscerated Trump’s campaign, calling it all flair and no substance, this might not matter to voters. Whether you’re trying to get someone to buy a product or vote for a candidate, studies have shown that appealing to emotion is nearly twice as effective as presenting facts or appearing believable.

As academics who study what makes advertisements successful and engaging, we believe Trump’s allure can be boiled down to three key factors, one of which—empowerment—encourages voters to actually work on his behalf.

Emotions influence behavior

But first, some background on the current understanding of emotional response in people.

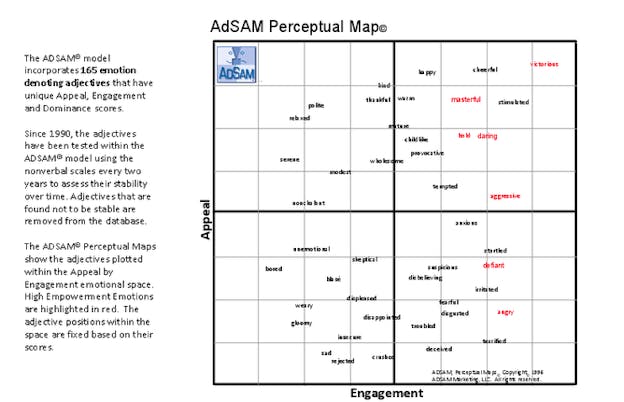

Studies have shown that humans interpret what they hear and see through an emotional lens that is made up of three mechanisms: appeal, engagement, and empowerment.

In a world where we’re bombarded with stimuli, from advertisements to buzzing phones, these mechanisms influence what we pay attention to, and how we react.

Appeal is simply the degree to which we judge something to be positive or negative.

Engagement is fairly self-explanatory: the extent to which an object or idea produces active or passive feelings—in other words, the level of emotional intensity it produces.

Lastly—and maybe most important—is empowerment, which is the amount of control someone feels in a given situation.

Until recently, researchers didn’t seem all too interested in empowerment. The lack of interest seems to have stemmed from a misunderstanding about this dimension, and insufficient empirical support of its effects.

And while appeal and engagement are pretty self-explanatory, empowerment is a bit more abstract. When we ask people how they feel, they can easily describe their current emotional state as either positive or negative and, to some extent, how intense that emotion feels.

In contrast, people can have a tough time delineating their feelings of empowerment, because being “in control” can’t exactly be expressed or felt in a direct or obvious way.

But this doesn’t mean that empowerment is irrelevant. Think about the emotions anger and fear. They’re both low in appeal (no one wants to feel angry or fearful) but have high levels of engagement.

So what makes these two emotions so distinctive from each other? Empowerment. When you’re scared, you feel like you’re not in control. But when you’re angry, you feel the irresistible urge to speak out and take action.

Empowerment’s potency

When it comes to the emotional appeal of an advertisement or politician, empowerment may be more important than we think.

We recently conducted a study on empowerment, and presented it at the Association in Education in Journalism and Mass Communications (AEJMC) conference this past August.

Analyzing an array visual ads and public service announcements, the research indicated that appeals to fear (like images of dead bodies on a battlefield) were associated with feelings of uncertainty and a lack of control.

People felt a sense of danger and became acutely aware of the cruelties of war, but didn’t feel like there was anything they could do about it. Therefore, they reported low empowerment.

In contrast, messages focusing on anger (like a PSA showing a healthy body being harmed by secondhand smoke) evoked appraisals of certainty and individual control among viewers, who felt a sense of responsibility to take action and help the victims. Therefore, people expressed high empowerment on the emotional response measure.

But perhaps most importantly, the study also showed that empowerment is in some situations a better predictor of behavioral intentions than appeal or engagement. In other words, high levels of empowerment trigger action, since people are motivated to seek solutions to the problems presented.

The findings revealed an important fact: feeling in control is highly related to people’s attitudes and behaviors on social, political and health-related issues.

In the case of communicating to the public – whether through television or social media—this study recommended that speakers and messengers attempt to tap into empowerment’s potency, using rhetoric and imagery that make audiences feel in control and able to enact change.

In most cases, that means appealing to or eliciting a sense of anger or indignation.

The Trump effect

It goes without saying that there’s a level of manipulation involved. The speaker must be adept at formulating a persona and message that resonates with audiences. Whether or not the message is grounded in reality—well, that’s almost beside the point.

Enter Donald Trump, who seems to have an innate mastery of this process. He is an ad-man’s dream, a political consultant’s perfect plaything.

Maybe he honed these skills during his years on network television; either way, he’s shown the ability to easily appeal to and engage with audiences, which he’ll do directly (“I will be the greatest jobs president that God ever created”) or indirectly (“the other candidates are dull and weak”).

But it’s the third and key element—empowerment—where he shines.

He’s able to consistently evoke issues in a way that makes people feel anger, rather than fear. (Some of his opponents use fear; for example, at the Conservative Political Action Conference, Ted Cruz told the crowd that the IRS “would start going after Christian schools, Christian charities, and…Christian churches.”)

And though Trump frequently raises issues that could elicit fear—terrorism, crime, economic collapse—he does so with indignation, which suggests that the audience should feel that way, too.

He’s angry, but not fearful.

That’s why he’s said that he favors soldiers that have been wounded over those that were captured: to Trump, surrendering under any circumstance connotes fear.

Then there’s Trump’s solution to the illegal immigrants who are supposedly overrunning the country: “throw the bums out, build a wall.”

As for China, he’ll argue that China is “stealing” jobs from the US (there’s the indignation)—and if he were in office, he wouldn’t let the nation “have its way with us.”

Furthermore, the feelings of anger he evokes lead to action on his behalf. Outraged voters are all too eager to post his videos on Facebook, retweet his tweets and promote his candidacy to friends and family.

Note what’s going on here: he simplifies complex issues, framing them in a way that’s intended to get a rise out of voters and infuriate them. But he presents solutions (often simplified, often unfeasible) in a way that comes across as clear—even obvious—and has the added benefit of making him appear in control.

In the end, it’s a calculated image that makes him an incredibly appealing candidate.

Look at what happens when you hold empowerment and engagement high for a person or product, while varying the level of appeal (click to zoom).

When moving a person’s appeal from “low” to “high,” a shift occurs in the way they’re described.

At the lower end, they’re called angry and defiant. But then, as their appeal rises, they become aggressive, daring and bold. Near the top, they’re described as masterful.

And when appeal’s at its highest?

Victorious.

This article was originally published on The Conversation. Read the original article.