A few years ago, teaching a class on the open road, I asked my students to read Echo Burning, the fifth of Lee Child’s Jack Reacher novels, published in 2001. Wandering a borderlands landscape populated by strong, dangerous, rapacious men—the sort of men one finds in the work of Cormac McCarthy or William Faulkner—Reacher is picked up while hitch-hiking by a beautiful Mexican émigré, who has been abused by her vile husband. The husband, in turn, is surrounded by a gang of criminals, each of them deserving extra-legal punishment. Reacher, after hearing the woman’s story, goes undercover as a day laborer and ranch hand, and, as the saying goes, hijinks ensue. By the end of the novel, the Texas countryside is painted red with blood, the entire legal establishment has been revealed as ineffective, and Reacher has administered his punishment. Then, as always, he moves on.

I’d asked my students what they thought of Reacher, and they suggested that he should stand trial for murder. Then, reading carefully through his interior monologues, they decided that he was insane and had him remitted to a high-security mental health facility. In our summary discussion, we talked a lot about Reacher as post-Cold War John Rambo, the Vietnam veteran suffering from PTSD who wanders into a small town in the Pacific Northwest and runs afoul of the local police. The point, for my students, was that Reacher should never have been set loose on the American countryside. Jack Reacher troubles me, too.

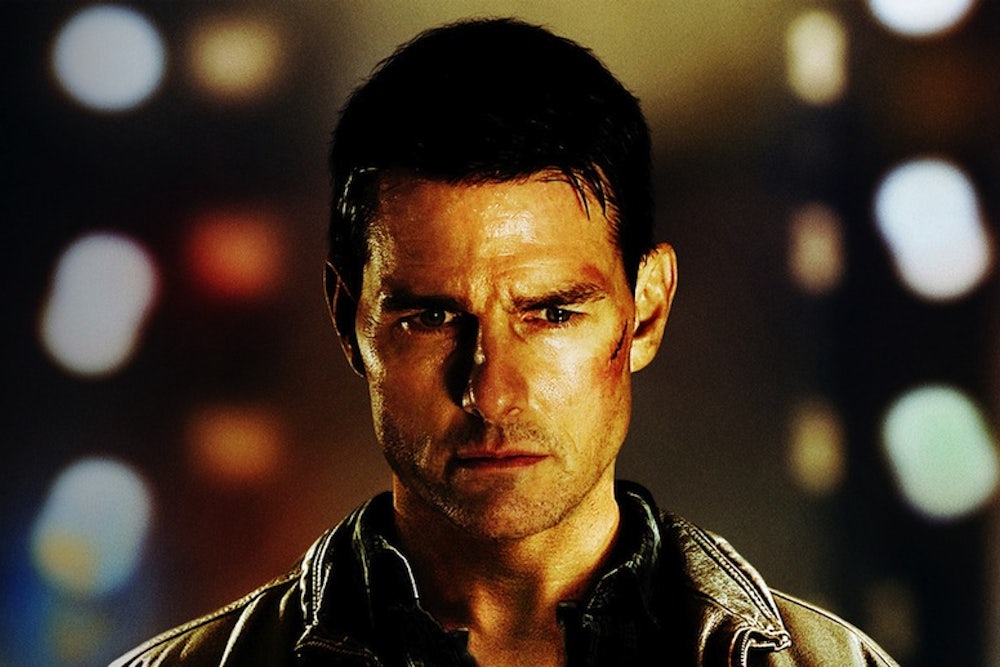

Lee Child’s new Jack Reacher novel is the twentieth in a series that dates back to the Clinton administration. Reacher is big business, of course. Last year’s installment, Personal, has sold 450,000 copies, and in 2012 Tom Cruise starred in an adaptation of one of the books. Classic pulp, the plotlines of each bestselling novel in the series feature lean arcs and little character development. Drawing from a handful of closely linked genres—police procedurals, mystery novels, mixing Tom Clancy and Clive Cussler—they contain much that is familiar and much that never changes. Formulaic literature, like serial drama, is popular precisely because it tells the same, comfortable story, with the same much-adored protagonists, over and over again. Indeed, one could lose a decade or two reading these novels and waiting for the moment somebody actually learns something new about themselves, and shifts direction or grows emotionally as a consequence. There is not a single existential moment in all twenty.

Fans will be thrilled, I’m sure, by the book’s title—Make Me—which accurately captures the protagonist’s distinctively gruff machismo. At six foot five inches, two hundred and fifty pounds of scarified military history, Reacher is an avatar of white masculinity in an age of radical transformations. The son of a military man, he is an armed forces brat who grew up abroad without any real experience of his homeland. Once a decorated military policeman and a scrupulous investigator, he is now a vagabond without a care in the world.

Make Me delivers exactly what regular readers of the Reacher novels have come to expect. There is a mysterious disappearance, a strong and beautiful woman, and a vast criminal conspiracy. There is a single enigmatic clue, discovered on a crumpled up piece of paper. Skulls get cracked. People die. Law enforcement will fail do much of anything, which means that Reacher will have to bring the hammer himself. (Cops are either ineffective or absent in the Reacher books; in Make Me, they are practically invisible). Moving briskly and with little adornment, the book underlines and highlights what we already know: that Reacher is the blunt instrument of justice sent, it seems, by the universe, appearing out of nowhere, turning the world upside down, and the disappearing at the end into the mist.

As an adult with a long, tawdry history of violence, Reacher is at home on the open road. Having been told where and when to move for most of his life in the army, he decides to wander aimlessly. He has no bank account. No apartment. No car. No gun. Everything he has in every one of these novels is something he has acquired recently and something he will discard soon. This includes, of course, the smart and strong women in each novel, who are either sexual or investigative partners, and often both. Judged on these facts, the wide-open spaces of the United States are, as common folklore dictates, a libidinous paradise for the freedom-loving, unbreakable white man on the move. Reacher is living the dream.

The open road and the open mind are, of course, regularly linked in American fiction and film. Linked, that is, in a sequence, as if the one follows the other. From the written work of Thoreau, Steinbeck, and Kerouac to the silver screen dreamscapes of Ridley Scott, Wes Anderson, and countless others, the pavement that connects the wide open spaces of the great American outdoors is a sort of existential proving grounds. Kerouac’s narrator, drifting across the continent on a series of half-hearted errands, realizes a certain kind of cosmic truth in the end. On the run to Mexico, Thelma and Louise “wake up” to the realities of patriarchy, and refuse to return to their sedate, stationary lives. A road trip, the genre tells us, is magically transformative; along with pain and suffering, it brings lasting wisdom and insight, a new sense of self and purpose. It remakes us.

The Reacher novels are, in a way, derived from this same national obsession with blue routes and blacktop highways. Fascinated by the freedom of movement, the former MP is routinely on a bus or a train to nowhere special, when whimsy leads him to stop for a moment in one town. Sometimes he is there to see a historical landmark. And sometimes he is drawn by a town’s name. (In Make Me, it is the enigmatic name, ‘Mother’s Rest.’) The whimsy is important, revealing a clever sense of humor, and an almost childlike interest in local history. Reacher’s open road, though, is filled with dangerous monsters. In most of Child’s novels, Reacher is just out there somewhere, wandering, drinking coffee and eating a plush breakfast at a diner. And then, with a jolt, he encounters some deeper injustice, and the “lizard brain” awakens. The monsters must then be crushed.

In Make Me, the hero—white and male—wanders a landscape where the police are incompetent, weak, or generally absent. He delivers justice without regard for laws, and wherever and whenever it is needed, from the city streets to the dense canopy of the jungle to the dry and dusty borderlands. This image of the pathetic civilian authorities, either entirely absent or extinguished quickly to make room for the “real” hero, stands in jarring contrast to what we see these days on the news: local police who look like military soldiers, equipped with body armor and automatic rifles and driving tanks.

Maybe our popular notions of justice are deeply, disturbingly disconnected from the law. Maybe, deep down, we imagine that justice comes from lawlessness, and not from a judge, or a trio of lawyers, or a constitutional scholar. It arrives with an epic beat-down, and not with a genteel summons to court. And it results, almost invariably, in a messy, bloody death. Jack Reacher, sociopath that he is, travels across the Great Plains in that Greyhound bus, plotting to break the bones and the bodies of the bad guys who lurk everywhere. That is a pretty terrifying thought.