On Tuesday, January 4, 1957, the Santa Monica Police Department responded to a call from Bess Eisler's, a local restaurant on Wilshire Boulevard. The bartender had gone to check on a customer who disappeared into the men's bathroom—only to find, gruesomely, that the man had shot himself in a stall. In his pocket was a polite, dispassionate note with instructions for informing his wife and detailing his desire that his body be donated to a nearby medical school. He also informed the police that the gun he used had been borrowed, and requested that they kindly return it to “[his] pal, Buster Keaton.”

The man in the stall was named Clyde Bruckman, and all but the most dedicated cinephile would be hard-pressed to list one of his credits even though, as a prolific writer and director of early Hollywood comedy, he worked with nearly every renowned star of the era. Keaton, Harold Lloyd, W.C. Fields, the Three Stooges, Abbott and Costello—all of them, at one point or another, owed a movie to Bruckman. Others, like Laurel and Hardy, may have owed him their careers.

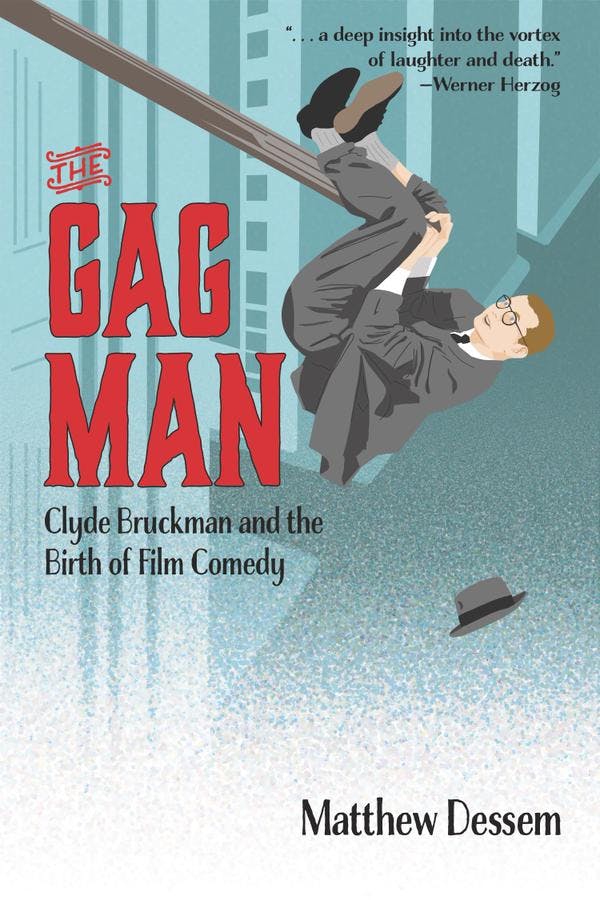

How did a man who helped produce some of funniest gags ever filmed wind up a forgotten suicide, a footnote in the biographies of his more-famous associates? The Gag Man, a book-length expansion by Matthew Dessem of his 2014 study of the same name for The Dissolve, doggedly pursues Bruckman into the recesses of Hollywood history, and into the potential tragedy that lurks, even today, behind every pratfall and spit-take. From stand-up specials on Netflix to the latest Tumblr meme, there's more comedic content available now than anytime since the days when the Keystone Cops cranked out films a dime a dozen—but are we always sure who, exactly, is making us laugh?

Bruckman's cautionary tale began auspiciously enough: After a brief career out of high school as a Los Angeles sportswriter, he started working for Hollywood in 1919 as a writer of intertitles for silent shorts—a job that required the kind of quick, pithy wit that, almost a century later, might've made Bruckman a Twitter sensation. He worked primarily with a long-forgotten screen duo called Lyons and Moran (whose work, like so many other silent shorts and features, is lost now), punching up already-completed films with his titles. It's difficult to attribute any one particular joke to him specifically, but Dessem gives a sense of the work Bruckman did on Bashful Jim (1925): In a scene where an old woman in a movie theater is supposed to fawn over the handsome leading man, Bruckman and his fellow title writers sharpened a rather dull first effort—“If he don't kiss her pretty soon I'll scream!”—into something far more biting: “I got his photo in a box of prunes!”

In 1921 Bruckman jumped to Buster Keaton's fledgling company, where, based on some combination of comedic talent, a passion for baseball, and mutual alcoholism, the two quickly became great friends. Bruckman served as one of Keaton's “gag men”—creative staff that devised funny scenes, situations and intertitles for comedies, but didn't necessarily receive any writing credit (the film's star would receive the lion's share of the public acclaim). All studios at the time had such teams on hand—Keaton had so many there were enough men to field two sides for baseball and play a couple innings during breaks on set.

But Bruckman was one of Keaton's favorites, and he worked on most of the star's biggest hits of the 1920s—Our Hospitality, The Navigator, Sherlock, Jr.—before finally receiving a co-director credit for The General, Keaton's masterpiece about a Confederate train engineer that is now widely considered one of the greatest silent films ever made. Bruckman's work in helping to wrangle an enormously complicated production was appreciated enough within the industry to earn him more writing and directing gigs. He'd bounce around from one comedian and studio to another for some time after, crafting films that varied in terms of creative success but were nearly always popular hits. Occasionally he even hit on both, as with The Battle of the Century, the Laurel and Hardy two-reeler that launched the pair to the A-list and features cinema's most legendary pie fight.

Films like The Battle of the Century demonstrated the vaudeville roots that still lay at the heart of early film comedy. When they started their careers on the stage, comedians like Keaton, Chaplin, or W.C. Fields made their living performing old routines with a fresh take: In vaudeville, it wasn't so much what you did but how you did it. That principle held true on screen for Bruckman—pie fights, for instance, were already old hat by 1927, but expanding the slapstick to include a cast of hundreds in a city-wide custard calamity took the gag to a new level. Reusing basic scenarios was standard practice at Hollywood studios—even a visionary like Keaton wasn't above it, following up the huge success of Harold Lloyd's The Freshman with his own campus-themed comedy, College. Recycling even more specific routines was considered acceptable as well; long before revival theaters and home video, reusing gags was sometimes the only way to keep them alive.

But as his career wore into the 1940s, Bruckman's line between “fresh take” and “retread” started to wear perilously thin. His functional alcoholism became gradually less functional, and he began returning again and again to ideas that had worked for him 20 years earlier. The last straw was an infringement lawsuit Harold Lloyd leveled at Bruckman for “stealing” gags from Lloyd's 1932 film Movie Crazy in a 1945 short for the Three Stooges. Never mind that Bruckman had co-written and co-directed Movie Crazy, giving him a pretty strong claim to intellectual ownership of the routine, or that Bruckman and Lloyd may very well have borrowed their ideas from a vaudeville act in the first place. A drawn-out court battle eventually landed Lloyd's way, with Bruckman's comedy publicly branded that of an outmoded hack. Bruckman was now a legal and financial liability, and his drinking sent him into a creative and emotional tailspin that ended in a bathroom stall in Santa Monica.

The question of who is responsible for a joke, raised by Lloyd's claims, feels startlingly relevant coming just weeks after Josh “The Fat Jew” Ostrovsky was accused by comedians and the internet at large for failing to properly attribute the jokes he “aggregated” on his Instagram feed. Like those social media users whose names Ostrovsky cropped out of existence, Bruckman became a victim of our casual disregard for intellectual property, particularly when it comes to comedy. What matters is how much we laugh, not how much creative effort was put into crafting, fine-tuning, and delivering a joke as a completed, marketable product. That tendency has only gotten worse with the internet—once a funny GIF goes viral, no one sharing it on Twitter or Facebook really knows who made it or where it came from.

Despite all the fun and games of comedy—in fact because of all the fun and games—we are likely making more Clyde Bruckmans every day. Whenever a big new Hollywood comedy is released (Trainwreck, Spy, Ted 2) there's often a lot of talk about the collaborative or improvisational nature on set. Credit gets passed between the biggest, starriest names, whether they're the lead actor, director, or producer—Judd Apatow, Amy Schumer, Paul Feig, Melissa McCarthy, Adam McKay, Will Ferrell, Tina Fey, etc. But what about an uncredited screenwriter who may have done a pass and punched up a gag or two? The cinematographer who found the perfect framing or the editor who knew just when to cut? Tracing a joke back to its origin, whether that be in the 1920s or two months ago, is a difficult and nebulous task, and the danger in not performing it might be greater than we think. As Bruckman's troubles proved, validating someone's intellectual effort is no laughing matter, even when it's literally a joke.

Giving credit where credit is due can be a difficult task, however, when the public record overwhelmingly favors the star-obsessed narrative. To that end, Dessem sets an impressive example to follow, diving deep into studio records, personal papers and trade periodicals to trace Bruckman's winding and often obscured path through the comedy scene—even when many of the short films Bruckman worked on don't even exist anymore. Furthermore, Bruckman seems to have only given one personal interview, and left only a few scattered pieces of correspondence, including an emotionally shattering letter written three years before his suicide to George Stevens, Bruckman's cameraman who had gone on to huge success as director of Hollywood classics like Woman of the Year, Shane, and Giant (the letter came when Bruckman was desperately seeking work—Stevens politely extended a $100 loan, possibly never understanding the significance of the exchange).

The overall lack of Bruckman's voice makes Dessem's meticulous reconstruction essential to understanding the gag man's life and predicament. Detail work has always been a strength of Dessem's—his blog, The Criterion Contraption, is notable for its formal close readings, breaking down narrative structures scene-by-scene, even frame-by-frame, to understand how film art functions. His work in The Gag Man is similarly exhaustive, drawing out a more complete, and wonderfully engaging, picture of Bruckman from a thousand fractured splinters.

Nearly 60 years after his death, Clyde Bruckman's public reputation, if he has any at all, is still largely based on a few sketchy details. Dessem's biography will hopefully correct that, but Bruckman's story remains a menacing example of the way that, even in a field as purportedly light and trivial as comedy, distortion, oversimplification and misattribution can linger, particularly when the alternative is so salacious. As of this writing, the longest and most detailed section on Bruckman's Wikipedia page, by far, is dedicated to Lloyd's infringement suit and the accusation of recycling gags. The section, in an irony apparently lost on whoever wrote it, has no citation. One wonders if that would have made Bruckman laugh.