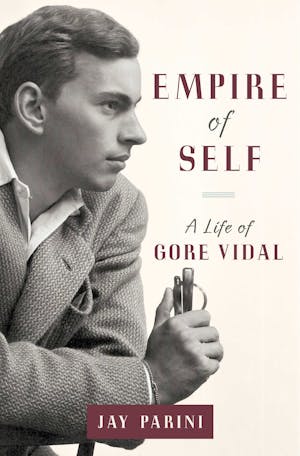

That Gore Vidal had a monstrous ego is proverbial; that he liked to make fun of that fact, and anything else, is more so. “Never lose an opportunity to have sex or be on television,” he liked to say, and he meant it. In his salad days, especially, he was a connoisseur of a kind of bloodless, indefatigable cruising, and other than (perhaps) Norman Mailer, no American writer made such a fetish of his own celebrity. Jay Parini, an old friend of Vidal and now his latest biographer, remembers entering the great man’s study in Ravello, Italy, and being struck by an entire wall of framed magazine covers featuring Gore Vidal. “When I come into this room in the morning to work,” Vidal explained, “I like to be reminded of who I am.”

In some respects Vidal, who died in 2012 at the age of 86, was a relic from an age of rarefied celebrity that is gone forever: the writer-hero who consorted with the Kennedys and pursued a political career in his own right; the sage whose controversial opinions were constantly in demand; perhaps our best essayist of the last 50 years, one of our best historical novelists, an outrageous satirist, and an unabashed hack who made a mint writing left-handed screenplays and pseudonymous potboilers. Such a massive cultural figure deserves a first-rate biography, surely, and yet: What particular aspect of Vidal’s polymathic output is most likely to endure?

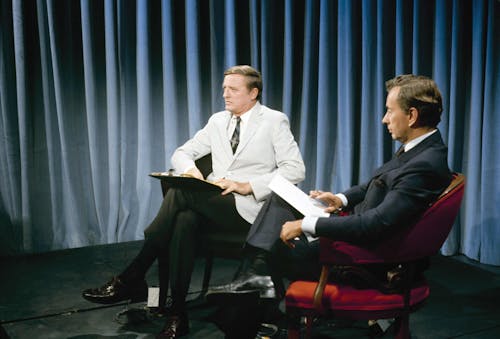

As shadows lengthen now across the greensward—as Vidal put it, by way of P.G. Wodehouse—how many discerning essay readers remain among us, and of those happy few how many would consider Vidal’s novels to be worthy of comparable notice? Not enough to suit Vidal, safe to say, who was haunted by a fear of the “Great Eraser” that had all but obliterated the reputation of his idol, William Dean Howells, the great realist author once known as “the Dean of American Letters.” On the other hand, this would seem to be Vidal’s moment: Apart from this latest biography and at least two controversial memoirs (Sympathy for the Devil, by Michael Mewshaw, and In Bed With Gore Vidal, by Tim Teeman), he’s been the subject of two major documentaries in the last three years, The United States of Amnesia and Best of Enemies—the second of which, especially, would seem to suggest that Vidal will be best remembered as the man who shattered, on national television, the tic-ridden but otherwise serene composure of his ideological opposite, William F. Buckley Jr.

Vidal was a man of infinite irony, but on some bedrock level his ambitions were deadly serious and sometimes noble. That he was expected to do great things was never in doubt. As a boy he was the constant companion of his maternal grandfather, Thomas Pryor Gore, the blind senator from Oklahoma whose staunch isolationism would have an enduring and somewhat curious influence on Vidal. His father, Gene, an Olympic decathlete and pioneering aviator, taught his son how to fly a plane and served as an affable counterbalance to the boy’s wayward mother, Nina, a self-absorbed alcoholic whom Vidal would later, reductively, claim to hate. As fate would have it, Vidal’s own grotesque dotage—as his protective facade of cool, elegant irony began to dissolve in liquor—left him resembling his mother more than ever.

His long, brilliant career arguably began as a desperate effort to stand on his own feet and be shut of Nina forever. Rather than join his Phillips Exeter classmates at Harvard, Yale, or Princeton, Vidal began writing a novel at age 19, Williwaw (1946), based on his World War II experience as first mate of an Army supply ship in the Aleutians. Within two years he became famous, after a fashion, when he published his third novel, The City and the Pillar, a succès de scandale with a gay protagonist. The arch-philistine New York Times reviewer, Orville Prescott, was allegedly so offended that he made sure Vidal’s books were henceforth not to be mentioned in the daily edition. Ever resourceful, Vidal wrote a number of mystery novels under such pseudonyms as Edgar Box and Katherine Everard (named after a gay bathhouse), before finding a more lucrative calling as a television scriptwriter. “Better to reign in hell than serve in heaven,” he remarked of this era, echoing Milton’s Satan, though the motto of the Wise Hack (as Vidal called a composite of his more seasoned screenwriting colleagues in his essay, “The Ashes of Hollywood”) was more to the point: “Shit has its own integrity.”

Vidal was at his best and worst as a political pundit and sometime candidate. In 1960, as the hospitable (and louche) proprietor of a Greek Revival mansion in Dutchess County, New York, he ran for Congress on a platform of taxing the wealthy, and, to his lifelong gratification, outpolled his friend Jack Kennedy in that strongly Republican district. In 1982, he ran for the U. S. Senate in California. On the surface these campaigns would seem quixotic at best, but Vidal was earnest in his ambitions and piqued at the people’s failure to choose the best man. “There is not one human problem that could not be solved,” he declared, “if people would simply do as I advise.” What he advised ranged from the well-considered (especially in his more temperate essays) to the far-fetched and downright crackpot. He obsessed over the “national security state,” which had transformed the republic, he believed, into a militaristic empire both morally and financially bankrupt. Fair enough. Nor was he alone in promoting the dubious claim that FDR had allowed the bombing of Pearl Harbor to proceed as a pretext for pushing the country into war. But as Vidal grew more paranoid, alcoholic, and shrill—not to say desperate for attention—he defended Timothy McVeigh as “a noble boy,” and almost predictably (by then) insinuated that President Bush had colluded in the September 11 attacks. Parini, for the most part, is careful to place such excesses into context, rightly emphasizing that a more lucid, objective side of Vidal “was able to lift his discourse above the petty” and write such astute historical epics as Burr (1973) and Lincoln (1984), perhaps the best of his Narratives of Empire, the seven novels that chronicle our nation’s descent into its present decadence.

Parini is the author of balanced, readable biographies of Robert Frost and others, as well as an acclaimed novel about Tolstoy, The Last Station (1990), and how he came to this particular folly is an interesting story he relates in his introduction. When it became apparent, in the early ’90s, that the critic Walter Clemons was unlikely to finish his Vidal biography because of ill health, Vidal approached his friend Parini with the project. Given their warm but fraught relationship (“I was looking for a father, and he seemed in search of a son,” Parini tells us on page two), and quite aware that the living Vidal would be happy only with the purest virtuosity and adulation, Parini tossed this hot potato to his worthy colleague, Fred Kaplan. Parini describes Kaplan’s book, Gore Vidal: A Biography (1999), as “sturdy and intelligent,” while also suggesting that it was something less than a page-turner and had displeased its subject immensely. Meanwhile Parini went his own way Vidal-wise, occasionally conducting interviews (as early as 1988) for a book of his own, and temporizing vis-à-vis his friend and father-surrogate until the man was safely tottering on the lip of the grave. “So write the book,” Vidal said, once Parini had finally committed himself, “and do notice the potholes. But, for God’s sake, keep your eyes on the main road!” Parini has been true enough to this desideratum, but I also think it’s fair to say that both Kaplan’s and Parini’s books are of a kind that Vidal himself would have savaged—the one as a numbing regurgitation of “scholar-squirrel” data, the other as hackneyed and lazy, and both (perhaps the keenest bodkin for Vidal) as humorless.

Humor, of course, is not just a matter of cracking jokes but a mode of understanding, all the more so when it comes to understanding Vidal and bringing him to life on the page. We never lose sight of Boswell’s admiration for his friend Dr. Johnson, even as the Great Cham’s laughable grossness (the lopsided wig, the bug-eyed gluttony) is evoked with such loving, firsthand particularity. As for Parini, he precedes his chapters with “suggestive vignettes” about his more memorable encounters with Vidal. What is mainly (if obliquely) suggested in these vignettes, however, is a kind of wistful exasperation on Vidal’s part toward his solemn, well-meaning protégé. “It’s a tragedy to see a man who could leap in the air in such a state,” Parini remarks to Vidal of a fellow dinner guest, Rudolf Nureyev, then dying of AIDS—whereupon Vidal “shakes his head, unhappy with [Parini’s] truism, offered as a way to fill an awkward silence.” Perhaps Vidal foresaw that his future biographer would be apt to write that same truism as cold, deliberate prose on the previous page of this very vignette: “It’s sad to see this wasted body occupied by someone who had leaped so high in his prime.”

What indeed did these two laugh about? Take the matter of Vidal’s florid sexuality—about which Parini’s grappling is akin to that of a greengrocer trying to fathom the uses of a speculum. “He certainly liked the idea of being bisexual,” Parini writes, going on to point out that a “note of self-hatred” is evident in Vidal’s tendency to refer to gay men as “‘fags’ and ‘degenerates,’ although he claimed to do so affectionately.” I doubt that “affectionately” is the right word, or the word Vidal used, though perhaps he thought it unnecessary to explain that such camp deprecation is mostly intended to mock the squares who mouth such slurs as a matter of course. In any event, Parini comes back to the theme eleven pages later, by which time Vidal has gone from wishfully bisexual to wishfully straight: “He never acted like a gay man,” Parini assures us—meaning he didn’t mince or lisp in any conspicuous way?—and adds: “He thought of himself as a heterosexual man who liked to ‘mess around’ with men.” As if sensing the reader’s confusion, Parini takes another swing at it 20 pages later: “Gore wrestled with his sexual identity, unhappy about it, never quite willing to acknowledge he was ‘gay,’ a term he despised.” Finally, after another 30 pages, he shambles full circle to his original claim that Vidal, by his own lights, was bisexual: “Yet his primary attachment to men, and to ‘trade,’ puts him mainly in the gay camp, however much he protested against such categorizing.”

But anyway: Why not simply let Vidal speak for himself? His personal ambivalence about being branded as one thing or another—there are “homosexualist” acts, he claimed, but no such thing as a homosexual per se—is reflected in his own abundant writings on the subject. These are tortured enough, to be sure, but they are sweet reason itself next to Parini’s repetitious murk. Meanwhile, as a public figure, Vidal’s stands on the issue were unfailingly brave and straightforward: “The difference between a homosexual and a heterosexual is about the difference between somebody who has brown eyes and somebody who has blue eyes,” Vidal said in a 1967 CBS documentary, facing down a grim Mike Wallace.

When a writer indulges in sloppy thinking, for whatever reason, the writing goes to pot, too. A good copy editor will warn authors when they step too close to the cliché line, but I imagine Parini’s editor throwing up her hands around page eight or so. Like a breathless press agent, Parini likes to describe things that excite him in terms of their sparkle—“This trashy but entertaining and sparkling novel”; “It was a glittering occasion, with numerous movie stars”—though he likes wind similes even more: “Gone With the Wind by Margaret Mitchell rushed like a tornado across the country”; “Streetcar Named Desire had swept the theater world like a hurricane”; “Fear moved like the wind in a forest.” And so on.

Perhaps the most well-known episode of Vidal’s public life were his televised debates with Buckley—“a pairing made in television heaven,” writes Parini—during the 1968 Democratic National Convention in Chicago. To a startling degree Parini manages, with a kind of ham-fisted legerdemain, to drain this great matter of its inherent drama, historical resonance, and psychological nuance. I was happy to see a number of factual howlers in the advance galley of Parini’s book corrected in a later version, but nonetheless one is advised to consult Kaplan’s biography—in this case particularly—both for the sake of basic accuracy and to get a better idea of the big picture.

For now I’ll focus only on Parini’s treatment of the actual clash between Vidal and Buckley. “They confronted each other like vipers, coiled and ready to strike,” he inimitably sets the stage, careful to point out that Buckley was the more viperish of the two, or rather a kind of cat-snake: “feline, a slithering presence, with his tongue flicking, his eyes leering.” As any remotely curious person knows in this age of YouTube, the money part of the debates (897,570 views as of this writing) came when Vidal called Buckley a “pro- or crypto-Nazi,” whereupon Buckley became viperish in earnest, calling Vidal a “queer” before ten million viewers and threatening to punch him in the face. When a nervous Howard K. Smith tried to remonstrate, Buckley said, “Let the author of Myra Breckinridge”—Vidal’s recent best-seller about a transsexual—“go back to his pornography and stop making any allusions of Nazism.” Or, as Parini sees fit to record it: “Buckley added with a wicked glare: ‘Go back to your [sic] pornography.’ ” But what pornography? We are left to surmise as much in Parini’s version, since he misquotes perhaps the most famous line from one of the most famous moments in Vidal’s life.

As for Vidal’s sad last years, the best account may be found in Michael Mewshaw’s mordantly perceptive memoir about his friend, Sympathy for the Devil, published in January this year. (It bears mentioning that both Parini and I provided blurbs for this book.) Mewshaw captures more vividly the decrepit gargoyle Vidal became after the death, in 2003, of his beloved partner of more than 50 years, Howard Austen, the one person who could stifle his more embarrassing rants. Certainly Austen might have urged him to skip being interviewed by Sacha Baron Cohen’s rude-boy persona, Ali G, who affected to mistake him for Vidal Sassoon (“You is also a world-famous hairstylist.”)

But let us end respectfully. Vidal’s life was a tragedy whose great themes put one in mind of Citizen Kane: the story of an insatiable egoist who had everything and lost it. Standing on his balcony in Ravello, overlooking the gorgeous coast, a friend asked him what more he could possibly want out of life: “I want to make 200 million people change their minds,” Vidal replied.