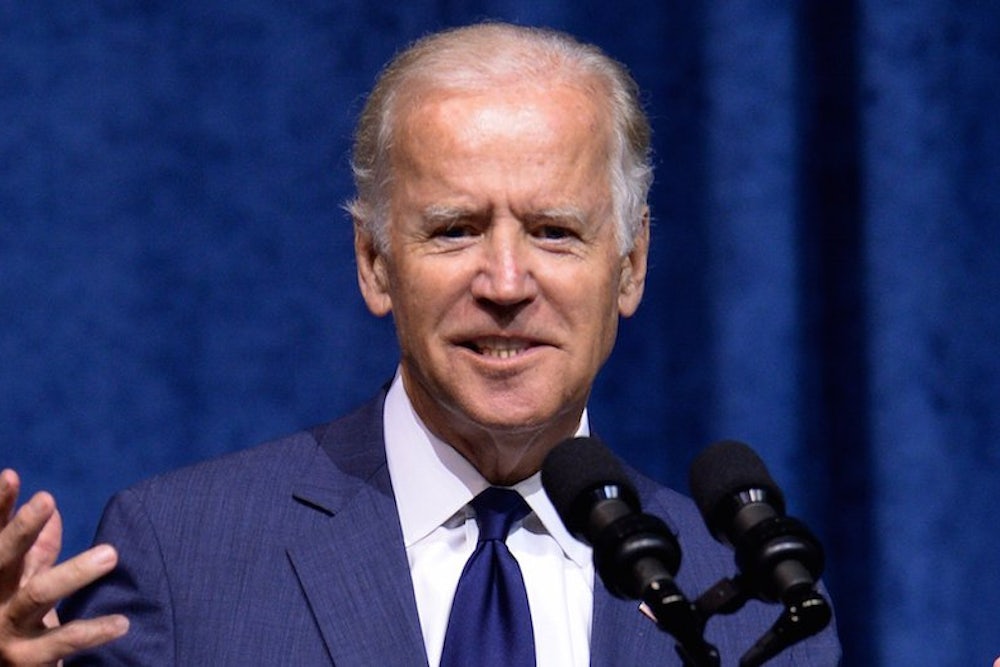

Why should Joe Biden run for president? For the Democratic Party, the political case for Biden seems fairly straightforward: He would be the liberal establishment candidate without Hillary Clinton's baggage, with a more telegenic smile and a more authentically folksy sensibility. But that’s not enough to make a winning candidate. Just look at what’s happened to Martin O’Malley, who’s tried exceedingly hard to run as a Generic Democrat, only to fall flat in poll after poll.

Of course, Biden has far more charisma, visibility, and experience than O’Malley, and he’d have more of the establishment machine behind him. But the reality is that while Clinton's poll numbers are softening, she still has a solid lead in both the primary and general election match-ups. Biden himself is unsure whether he has the "emotional fuel" for a run, or whether his family is ready either. If he does jump in, though, he'll need to carve out an identity and case for his candidacy that’s more than being the anti-Hillary or the lovable vice president.

Ideologically, there isn’t much that would distinguish him from Clinton—especially in terms of the main issues that Democratic primary voters seem to care about. That’s partly because the Democratic Party has become significantly more unified on issues like economic policy since the fight over deficit reduction has receded. The domestic proposals that Clinton has rolled out so far—on college affordability and universal pre-K—have felt like the third term of an Obama presidency. Biden could argue that his experience makes him the more natural successor, and that his blue-collar roots in Scranton, Pennsylvania, make him a more authentic messenger on inequality. But that's still not much of a distinction.

There’s more daylight between the two when it comes to foreign policy. Biden has generally been less hawkish than Clinton—and many of his colleagues in the White House—when it comes to military intervention. He opposed the Libya intervention, the 2009 counterinsurgency operation in Iraq, and arming the Syrian rebels. And he was skeptical about the raid on Osama bin Laden’s compound, which was ultimately successful. Broadly speaking, however, Biden and Clinton share a similar ideology of liberal interventionism and faith in building multinational alliances. And on the issue that’s most sharply dividing Democrats—the Iran deal—both have firmly defended the president.

Even their policy weaknesses in the Democratic primary are similar. While progressives are wary of Clinton’s ties to Wall Street, Biden comes from Delaware, the credit card capital of America. As with Clinton, big financial firms have been major donors to his campaigns. In the Senate, Biden and Clinton each voted on separate occasions for bankruptcy bills that consumer advocates like Elizabeth Warren vocally criticized. And Biden would be even more vulnerable to attacks on his criminal justice record. While Clinton supported her husband’s tough-on-crime initiatives in the 1990s, Biden was "the Democratic face of the Drug War," as Slate's Jamelle Bouie explains.

So how would Biden actually distinguish himself? He’s a throwback to the old days when leaders in Washington “put personal relationships ahead of politics,” said Democratic strategist Steve Schale, director of Obama’s 2008 campaign in Florida, who recently joined the “Draft Biden” super PAC. In certain ways, Biden never stopped being an Old Bull of the Senate, negotiating behind closed doors at crucial moments with Republicans.

Biden worked closely with then-Senate minority leader Mitch McConnell on the biggest budget negotiations of Obama’s first term, drawing on their long-standing relationship in the Senate. In 2011, they hammered out the $2.1 trillion deficit reduction deal that resulted in the Budget Control Act. In early 2013, they reached a deal to avert the so-called fiscal cliff, which extended unemployment benefits as well as most of the Bush tax cuts. “Every time we get to the edge, it’s Biden who goes in and cuts the deal with McConnell—he’s got that history, there’s a trust and confidence,” said Schale.

The White House dispatched Biden in part because the president himself didn’t have the personal history or the temperament to wheel and deal with Republicans in Congress. “I think the president's relationships with Congress have made it very difficult, despite the fact that Biden and McConnell get along fine," the Bipartisan Policy Center's Steve Bell, a former GOP aide to Sen. Pete Domenici, told USA Today in 2014. Biden’s love for the personal side of politics was one reason he was tapped as Obama’s VP pick to begin with. And that’s helped the White House outside of Congress as well. Jared Bernstein, the vice president's former economic adviser, recalled Biden’s approach to ensuring that the 2009 stimulus was working, when Obama tasked him to oversee its implementation. “He was literally on the phone with governors and mayors trying to make sure that things were happening the way they were supposed to,” Bernstein said.

Certainly, these aren't Clinton's key strengths. Republicans have harbored a special kind of animosity toward the Clintons, and Hillary doesn't have the same talent for retail politics as her husband. Biden could try to make the case that he'd be a more credible, effective leader, given his ability to build those relationships across the aisle. But that could be a very hard sell for American voters who've grown increasingly disillusioned with Washington's ability to function on the most basic level.

Biden's successes as dealmaker came at a time when both parties still believed that big, bipartisan dealmaking was possible and desirable. By the end of 2013, however, it was clear that Republicans were significantly less willing to compromise. Dealmaking gave way to pure brinksmanship. Republicans shut down the government when Democrats refused to budge on defunding Obamacare. (Harry Reid had planned on taking a similarly confrontational approach during the 2012 fiscal cliff fight, but the White House shunted him aside to have Biden negotiate instead.) And these kinds of standoffs are likely to continue if there's another Democratic president, as Republicans are likely to keep control of Congress.

To that end, a campaign that paints Biden as a bipartisan dealmaker could have a tough time gaining traction in a Democratic primary. It’s true that far more Democrats (52 percent) than Republicans (34 percent) want both parties to compromise, even if it disappoints some supporters, according to a 2014 Pew poll. But 43 percent of Democrats want the president to “stand up” to Republicans, even if that means getting less done—a figure that’s risen since 2012.

That's certainly been the M.O. of second-term Obama; candidate Obama's promise to transcend partisan politics seems almost quaint at this point. The very deficit-reduction agreement that Biden brokered in 2011 with McConnell is a prime example. That deal set up the bipartisan supercommittee tasked with crafting a "grand bargain" to reduce the deficit, but it failed when Republicans refused to raise taxes, and Democrats refused to budge on entitlements until they did, prompting sequestration to take effect. To this day, we are living with the austerity mandated by that deal, arguably the worst fiscal policy that the White House embraced. Reversing it would require a level of bipartisan cooperation that no one seems to be expecting anymore. And the 2016 Republican primary has shown how much further the GOP may be willing to lurch to the right, turning into a party that Democrats may be less willing and able to compromise with.

The case for Biden would require a certain kind of faith: that Washington can work again, that friendship can matter more than partisanship, that being a good guy is enough. And it will be hard for him to make that case—one that's essentially about his character—without going on offense against Clinton. That could get very ugly, as Michael Tomasky points out: "He’s going to have to run a campaign that says, sub rosa: 'I’m a stronger and safer nominee because she’s corrupt.'" Ultimately, it won't be enough for Biden to convince voters that he has fewer problems than Clinton. He has to convince voters that he's the solution, too.