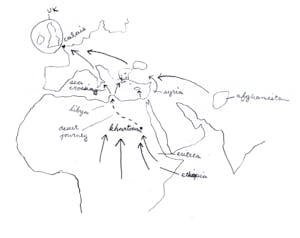

The trip out of Khartoum began with a smuggler, a 22-year-old Ethiopian man tells me. We are in Calais, France. He was crammed in a lorry with 30 people. They traveled across the Sahara Desert to Libya. “That is long,” he says. “Twenty days.” Vehicles get lost, or stuck in the sand. “We have no water, no food.”

It so crowded that everyone had to take turns hanging off the back, in 20-minute shifts. When migrants fell off, the driver didn’t stop. They were left for dead.

In Libya, he was thrown in jail for two months.

“You are tired you are hungry. You do not speak. If you speak, they hit you. Some died.”

Calais is a port city in northern France, the point where mainland Europe connects to England via the “Chunnel,” a 50-kilometer rail tunnel underneath the English Channel. For months, it has been one of the most dramatic scenes in an unprecedented global migration, primarily from Syria, Afghanistan, the horn of Africa, and Iraq into the European Union.

People seeking economic opportunity or safety from war started as far away as Afghanistan and Ethiopia, following routes they learn of via word of mouth and rumor. The most common images of this migration feature hundreds of people huddled on sinking boats in the Mediterranean, or thousands rioting on Greek islands. The sheer magnitude of the crisis has prompted despair and outrage in Europe, particularly in the United Kingdom, where Prime Minister David Cameron controversially referred to the migrants as “a swarm of people coming across the Mediterranean.”

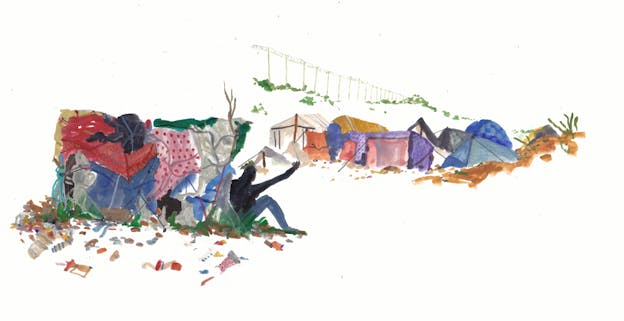

Calais is the final stage of a journey that can take a year to complete, but also the most difficult hurdle many of these migrants will face. Many have attempted to stow away in semi-trucks, or cling to trains bound for the Chunnel. Others have paid off human traffickers, or even tried to swim. But many of them, due to injury, exhaustion, or despair, are stuck in Calais. They live on a 40-acre plot of land on the outskirts of the industrial section of the city, a shantytown made of rubbish, found materials, and wood from nearby rural areas. It is the improvised product of thousands of people from around the world, some of whom stay only a few days, others who have been there for months.

It is called the Jungle.

There is a hotel, a school, shops, a chicken restaurant, a bicycle repair area, a church, a mosque, and four “embassies,” which are big tents with the names of countries written on them. The Afghan owner of the chicken shop, incidentally, snores.

When people talk about the Jungle, they tend to say it is different at night. “People are drinking. People are fighting,” the man says. “The police do not come.”

At first, migrants waited for traffic to stall on the highway that leads to the Chunnel. They would run up onto the highway, pry open the backs of big trucks, and climb inside, hiding among the cargo. This led to confrontations not only with the French police, but truckers as well.

The authorities built two layers of fence between the Jungle and the highway.

Migrants’ next method was to run alongside departing trains and climb onto them, stowing away on the carriages. Ten have died since late June.

I arrive at the Jungle early in the morning. There is a tall man in a muscle tee bullying the migrants. He is putting his finger into the chest of a skinny Sudanese guy. “Two-thousand pounds, mate! Two-thousand pounds!” I assume this man is a smuggler. I go the other way. Later, he steals cigarettes from an Afghan man’s store.

There is a lawless feeling here, as if in the middle of Europe there is a frontier, a small bubble where the rules of the developing world are used, rather than the strict order you find in the rest of Calais.

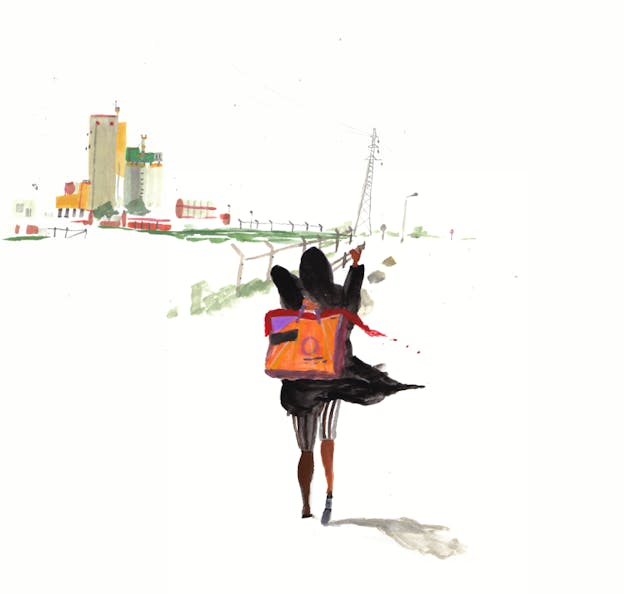

The migrants are mostly young, and mostly men. There are, however, women, old people, and children. They are determined and resourceful. If they were not, they would not be here. Despite the fact that many of them arrive on their own, they quickly form into small families or units, and spend the day sharing knowledge they have gathered about immigration procedures, movement methods, and stories of success and failures. While some seem confused and hopeless, others are highly attuned to the nuances of their legal status.

“Fish!” they say. They hold out their hands flat. “A fish!”

I don’t understand what they are saying at first. An Eritrean man explains that if they catch you in Italy, they make you a fish: They jot down your name and take your fingerprints. Then, even if you make it to the UK, they check your fingerprints. If you match any fish, they send you to the country where you were caught before.

“In Italy, you are clear?” I ask.

“I have not anything.”

They laugh and clap their hands, they wave their hands: They have no papers, they’re all clear.

Food is delivered once a day, a big piece of bread that migrants ration throughout the day. Water comes from several taps that quickly become crowded. The sanitation situation is not much better. Piles of rubbish are growing rapidly, and disease is spreading.

When you walk to the camp you pass by big industrial factories. It is a long walk, and creates a feeling of isolation in the Jungle. To get to town takes about an hour and 15 minutes. Once every so often, a Catholic church gives out clothes and blankets. On those days, the people walk to town in groups of two and three. I walked with an Ethiopian and an Eritrean. They waved and said hi to everyone. It reminded me of the first day of university, when everyone acted friendly to mask their fear and insecurity.

The Eritrean man pauses. We are at a canal. There is a boat there that is slightly longer than a school bus. He says it’s like the one he came in, but it was packed with hundreds of migrants.

I ask him if he was able to bring anything with him from Eritrea. He reaches into his shirt to reveal a necklace with two charms, a cross and a heart. “This is my God, this is my child—this heart.” He hooks his cheek with his finger and says he hid the charms in his mouth.

He is one of the only people I meet who managed to keep something from his home country.

In Calais, many people fall off bikes. Curbs and train tracks are the most common hazards, but even biking while talking can be difficult. They use the bikes to travel between the Jungle and Calais, and they have never ridden them before.

The Ethiopian guy tells me they aren’t used to riding bikes. “They can’t do it,” he says. “I can drive it.”

As we are talking, another two African men fall off bikes right in front of us.

“Okay?!” he shouts. The men laugh and wave.

Some locals are friendly with the migrants. Some even volunteer, and carry food and supplies to the camp. Some gesture or stare. Most look straight ahead, avoiding eye contact. But others are hostile. They say “hey nigger,” the Eritrean man tells me. “The glass, he hit you, the bottle.”

I am walking back from the camp when I hear a clicking noise and a loud voice speaking Arabic. I turn around and see two kids. One is wearing a Hawaiian shirt with parrots on it, and a bright green visor.

He is 17, he comes from Asyut, a city south of Cairo, Egypt.

He lived with his father and mother on half a hectare of land. One day, his father accidentally flooded the alfalfa field. He forgot to turn off a pump, and all the crops died.

The father’s brother came over and started fighting with the father, angry about the flooding. The brother said, “What the fuck, you flooded the harvest. My uncle hit my father and they got into a fight. So my dad got the rifle and shot him and killed him.”

He tells me that after his uncle was killed, his uncle’s family vowed to kill the first-born son of the killer. So his father told him to go away. He told his son, “Go to Libya and see what you can find. Go to any fucked up place, just get away from here.”

“I haven’t spoken to him after that,” the Egyptian kid says. “I haven’t spoken to him in five months. He knows nothing about me.”

He says that Libya was the worst place on earth. He crossed the Mediterranean on a Zodiac, and is trying to reach England to find his cousin. His cousin is successful, and had tried to help him enter legally, but it didn’t work. There was no one here to help him fill out the papers, he says.

The kid says he doesn’t think he will get into England. “England is difficult,” he says. “There is no work.” He asks me if I know any countries he can get into that have good schools. “I want to go to Paris.

“People should just thank God they came out of the water and lived. They should thank God they are in France. Her laws are good. There are rights.”

Then he asks for a drink of water.

A 50-year-old Syrian man is seated in a tent smoking a cigarette. He is with three other men, two Syrian Arabs and a Syrian Kurd. When I walk up, the Kurdish man, the youngest, about 40, offers me his chair.

The smoking man says his house was destroyed. He makes a flattening motion with his hands. The regime bombed his house.

“Do you have family?” I ask him.

He says he has a wife and three children. They are in Raqqa. The Islamic State took them. The man shows me a picture of his kids. They are sitting on couch in a sunlit room. The youngest, a boy, is smiling, looking at his brother and sister.

The man to my right says that his wife was in Hama, a city devastated by barrel bombs, chemical weapons, and months of urban warfare. The other man, who has not spoken much, says that his family is dead.

The four of them came on foot, via Turkey. Then they made their way to Calais, by foot and sometimes as stowaways on trucks. “If Syria got better I would return tomorrow”—he looks up at the sky—“if bombs stopped falling.”

Most of the migrants are very touchy about having their faces seen. They are nervous. The smoking man is much more fatalistic. He tells me to show his face, that he doesn’t care.

The 22-year-old Ethiopian man looks out at the fence. “I miss my country,” he says. “It’s better to go back.”

He’s been on this journey for six months. Now he’s 17 minutes away from England, he says. “It’s so close.”

This article has been updated to account for discrepancies between direct quotes and the writer’s interview notes and audio recordings.