The partisan debate over international efforts to forestall an Iranian nuclear weapons program has been stuck in a loop of self-parody ever since Israeli Prime Minister Benjamin Netanyahu attempted to sabotage the negotiations with an address before Congress this past March. In the ensuing months, Republican opponents have continuously echoed Netanyahu’s unsubstantiated insistence that he and other Iran deal skeptics don’t propose war or regime change or outright failure to keep Iran from manufacturing a weapon, but a "better deal," the particulars of which remain mysterious to everyone.

"We're being told that the only alternative to this bad deal is war," Netanyahu said in his joint session address. "That's just not true. The alternative to this bad deal is a much better deal."

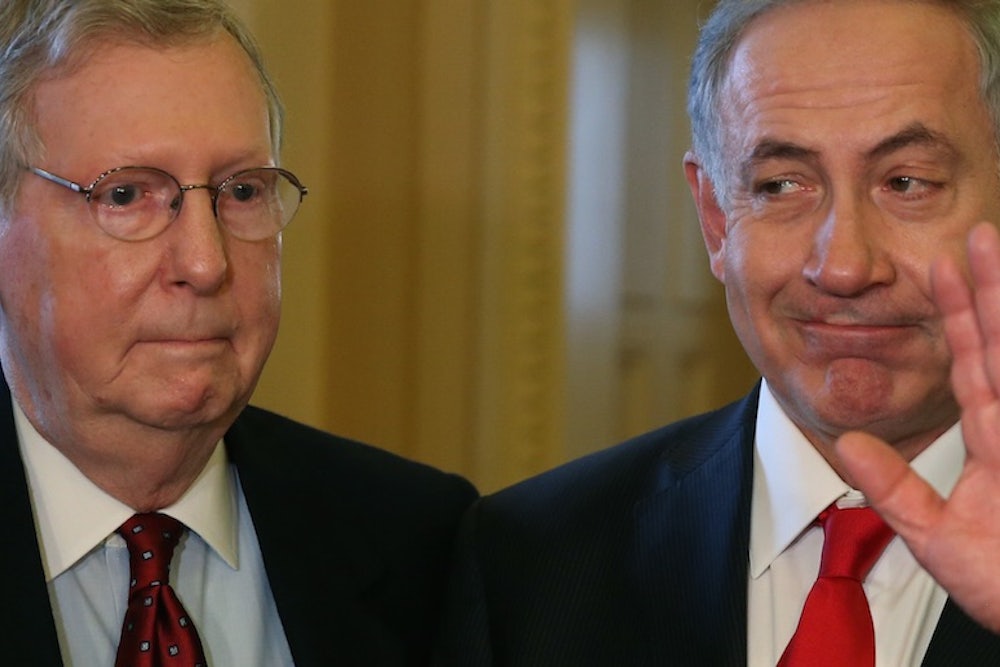

"It's either this deal or a better deal, or more sanctions," Senate Majority Leader Mitch McConnell argued just last week.

The putative existence of this “better deal” is meant to trump supporters of the global powers agreement, who argue quite sensibly that the agreement itself must be held up against an array of feasible alternatives, rather than a fantastical scenario in which Iran capitulates to every demand Netanyahu would have made. Netanyahu and Republicans can’t articulate a preferable, feasible alternative, but they also don’t like the intimation that their position amounts to a Trojan Horse, so they say “better deal” over and over again, overwhelming the entire debate with vagueness, deception and hysteria.

But there’s something particularly maddening about this story, above and beyond the fact that the deal's opponents are equivocating and hiding the ball and generally unwilling to level with the public about their goals. The structure of their critique suggests not that they think cutting a deal with Iran, in which everyone makes concessions, is per se unwise, but that the global powers screwed up the negotiations and gave away too much. They argue in essence that the diplomacy was conducted incompetently, and that they would’ve done a better job.

But there is no reason to believe this, because so many of the deal's prominent critics have thin or failed diplomatic records of their own or have built their careers around the notion that negotiating with enemies is a sign of inherent weakness.

Netanyahu epitomizes the disconnect better than anyone else. Why should anybody in America or anywhere lend a favorable view to to Netanyahu’s pronouncements about diplomatic tradecraft? He doesn’t boast a record of cutting "better deals" or even really of cutting deals at all. To the contrary, the political balance he’s struck in Israel, quite transparently, is to promise a “better deal” with Palestinians at some point in the future, while governing without any intention of reaching it. As his most recent election approached, he briefly campaigned on the promise not to cut one, then sheepishly and unconvincingly backtracked after his premiership was secured. He’s brokered no major deals elsewhere in the region, either, or really treated diplomacy as a useful problem-solving tool in general. Viewed as a diplomatic effort, his campaign of sabotage against the global powers agreement is a reckless disaster, which risks causing irreparable damage to the relationship between his country and its one true, powerful ally.

To underscore that point, there is a pronounced strain of thought within Israel among skeptics of the agreement that Netanyahu is making a profound error by waging a scorched-earth campaign against it—that the only thing worse than the deal itself is interfering to sabotage it. As the Wall Street Journal reported this weekend:

In unusually direct terms, Israeli President Reuven Rivlin this week warned Mr. Netanyahu that his aggressive campaign to defeat the deal risked harming a relationship central to Israel’s security. "The prime minister has waged a campaign against the United States as if the two sides were equal, and this is liable to hurt Israel," Mr. Rivlin, a member of the premier’s Likud party, said in an interview published Friday in the daily Maariv. Yedioth Ahronoth and Haaretz carried similar interviews with the president.

"I have told him, and I’m telling him again, that struggles, even those that are just, can ultimately come at Israel’s expense," said the president, adding: "We are largely isolated in the world."

This isn’t a quirk unique to Netanyahu either. Most Republican presidential candidates have adopted the same approach to global affairs. They support a comically ineffective embargo over normalization with Cuba. They debate each other, as Scott Walker and Jeb Bush just did, over whether it might be necessary to bomb Iran on the first day of a Republican presidency, or only after waiting to get a cabinet in place. President Barack Obama’s foreign policy record isn’t unblemished, but he can boast of real diplomatic successes—reaching climate change agreements with China, Brazil, and Mexico, re-establishing relations with Cuba, to say nothing of the global powers agreement itself. Republicans, by contrast, say things like, “What we object to is the President's lack of realism—his ideological belief that diplomacy is good and force is bad."

Yet at the same time, they stipulate that critics should take their promise that a “better deal” is possible at face value. In this way they are like, well, themselves, in the domestic realm—forever promising to repeal Obamacare and replace it with “something that doesn't suppress wages and kill jobs,” or “something terrific," without elaboration. Another “better deal” that for some reason can’t be put to paper in a way that convinces anyone of its seriousness. But at least in the similarly farcical debate over Obamacare, much of the public has learned not to place stock in promises like this. The same can’t be said of the Iran deal opponent’s false promises, and against that backdrop the Republican position is beginning to seep into the mainstream.