The first round of Republican presidential debates could have been worse. The main event on Thursday night opened with a spat between Rand Paul and Donald Trump and appeared headed for multiple bouts of shrill internecine Republican bitchery, then somehow settled, as these things typically do, into a bout of dueling position statements. But there was an interesting debate that unfolded beneath all the bluster and rhetoric: the question of which Americans should be the objects of Christian political action.

Which is to say: For those hoping to enact an authentically Christian politics, does it make more sense to try to stop or punish people who are behaving immorally (ostensibly for the benefit of people who are behaving morally) or to try to help or heal people who are behaving immorally into people who behave morally, with at least a partial focus on their own benefit? The differences here are subtle, but they have informed disagreements between Christian politicians in America for quite a while, and the distinction between them was especially evident in the debate.

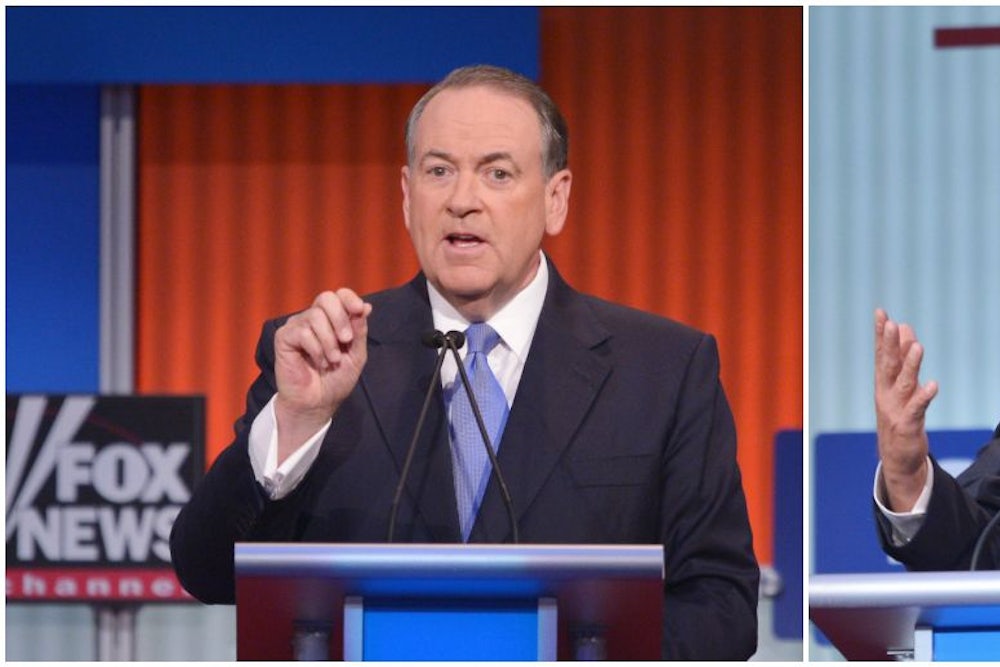

On the classically Evangelical front, former televangelist Mike Huckabee took a pretty old-fashioned Christian right tack. In explaining how he would reform social security funding, Huckabee said “[social security and Medicare] ought to be a transformed system” because they are currently strained by “illegals, prostitutes, pimps, drug dealers, all the people who are freeloading off the system now.” In other words, Huckabee’s reforms would ensure that only people earning legally taxed wages would have access to Medicare and Social Security, while those earning income under the table would, ostensibly, lose their access. The idea is to save government benefits for the really deserving, in part by punitively denying service to the undeserving and immoral. (For the record, the former Arkansas governor is wrong about people with untaxed earnings receiving Medicare and Social Security.)

Then there was Ohio Governor John Kasich, who, despite being somewhat inarticulate and notoriously offbeat, has managed to pull together a curious sort of Christian street cred. Confronted with his past remarks about basing his decision to expand Medicaid in his state on his Christian commitment to the poor—his “Saint Peter’s rationale,” as host Megyn Kelly termed it—Kasich explained that had played out well for Ohio. He spoke of reaching out to “people who live in the shadows” of society, and pointed out that expanding Medicaid had allowed Ohioans with mental illness and addiction problems to receive treatment rather than sit in prison, a common destination for people with untreated addiction and mental health issues. Kasich added that expanded Medicaid allowed the working poor to receive healthcare in order to “get them on their feet,” though he didn’t meditate on whether or not their jobs would make them respectable in the eyes of genteel society.

All in all, the distinctions between Huckabee and Kasich are relatively subtle: They were among the few Republican contenders defending government welfare services whatsoever. But their difference in focus animates a fissure in Christian politics that will likely grow more prominent as the 2016 campaign advances, especially after Pope Francis’ September visit to the United States. And that fissure reflects a growing divide in Republican thought: Is the world made up of makers and takers, with the immoral takers always out to swindle the honest, hard-working makers out of their earnings? Or is the world rather made up of all sorts of broken people, some suffering and damaging to greater degrees than others, but each with an equal claim to their portion of the world's bounty? The latter seems to me more defensibly Christian, but less reliably woven into Republican politics. Whether or not Kasich's brand of Christian conservatism gains widespread purchase will likely depend on whether or not traditional "47 percent" rhetoric appeals as much in this election as it has in elections prior. It's early yet, but Thursday's debates gave little reason for hope.

This article has been updated.