Like the British after Dunkirk, the proponents of Medicare look on the battle they fought and lost this year as a strategic victory. They are convinced they will be stronger when the fight is resumed in the next session of Congress.

Representative Wilbur Mills of Arkansas once again proved to be Medicare's most formidable foe. Mills, whose power as chairman of the Ways and Means Committee is legendary, remains an enigma to his House colleagues. Brilliant and thorough, a shrewd manipulator and a skillful debater, he led the successful fight for the trade bill and the tax cut, both dear to the Administration. But he has spurned the pleas of two Democratic Presidents and prevented Medicare from coming to a floor vote. Mills has long claimed that he has compassion for elderly men and women faced with crushing medical bills. But his chairmanship of Ways and Means, he maintains, gives him a special responsibility for watching over the social security system. For six or seven years, Mills has rejected the blandishments of the Medicare proponents and the Health, Education and Welfare statisticians to argue that any health plan tied to social security will inevitably lead the entire system to insolvency. On a moment's notice, he will break out a bewildering array of figures to prove that Medicare is financially unsound, and buttress his position by citing the experience with health plans of countries all over the world. Mills swears that only his fear of a bankrupt social security fund keeps him opposed to Medicare. But whatever his reasons, he has become the leader of the conservatives on the Ways and Means Committee, and he effectively resisted every attempt to have a House majority take the Medicare decision.

Through most of the past session Medicare's proponents despaired of overcoming the Mills roadblock. When President Johnson included Medicare in his basic legislative program, he was not taken seriously. But late this summer, pro-Medicare Senators led by Clinton Anderson of New Mexico announced their intention of attaching the proposal to a bill that would at the same time raise social security taxes and increase cash benefits. They reasoned that in an election year the temptation to pass such a bill—with or without Medicare attached—would be almost irresistible. Their tactic was to inflate the cash benefits in the Senate bill, to the point that a grateful Mills would accept, as a compromise, some sort of Medicare that would retain the soundness of the social security fund. The Medicare forces also counted heavily on Mills' party loyalty and on new pressure from his constituency, which since the 1962 election has been redistricted to include Little Rock, where the labor lobby is relatively strong. On September 2, the Senate by a vote of 49 to 44 passed, as planned, the Medicare amendment to the social security bill. The package then went to a House-Senate conference to be reconciled with Mills' bill, which was not only without Medicare but contained much more limited cash benefits.

The membership of the conference committee was unfavorable to Medicare. Of the seven Senate members, only Anderson, and Gore of Tennessee, had voted for the amendment. Of the five-man House delegation, which Mills naturally dominated, only two members favored Medicare. It was a surprise when Long of Louisiana and Smathers of Florida decided to support the Senate version of the bill. Then Mills declared himself willing to discuss a reasonable compromise, and for the first time the Medicare forces believed they might get a program, though a limited one, and began to issue optimistic reports.

But though Anderson offered Mills virtually anything to meet his standards of fiscal integrity, including the establishment of an entirely separate fund with a separate name, the conferees haggled almost a month without result. Had the House Democratic leadership been confident of winning a floor majority, it might have called Mills back for new "instructions." But Mills, who had earlier rejected any vote on "instructions," had no intention of swallowing a Medicare mandate from the House and made clear that he would risk his considerable prestige in such a contest. The leader- ship, respectful of Mills' power, was unwilling to chance losing the first and, to date, only floor test of Medicare, in the end. Mills volunteered to bring Medicare back to the House himself, but under a procedure that would have first subjected it to the scrutiny of the Rules Committee. Aware of what the Rules Committee would do and suspecting a trick, the Senate conferees angrily rejected Mills' offer. Thus, in an atmosphere of bad temper, Medicare was lost.

Anderson and his followers now had the choice of walking out of the conference or coming to a compromise with Mills on the cash benefits alone. The House had passed the Mills bill by a vote of 388 to 8 and the members obviously wanted to appear as champions of social security in the election campaign. The pressure on the Senate group was severe. In the end, it was from the White House that the word came to hold firm. It was felt that cash benefits this year might rule out Medicare in the next Congress. The conference collapsed and a social security bill was dead for 1964.

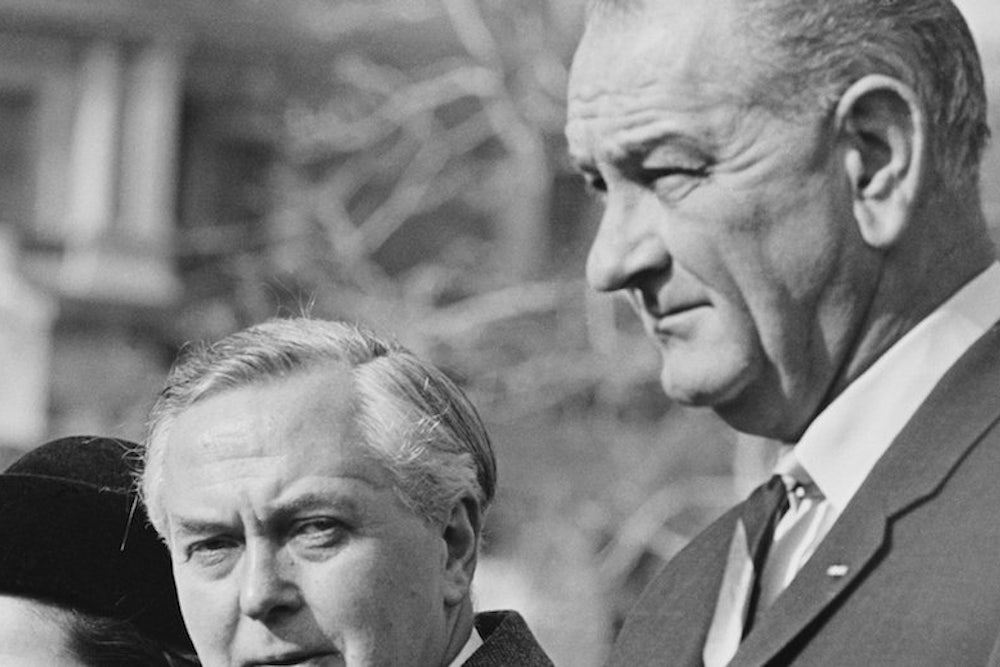

Despite Mills being one of their own, Johnson and Humphrey will campaign hard for Medicare in the coming weeks. The National Council of Senior Citizens, the strongest Medicare lobby, accepted the defeat of the social security bill, denounced Mills, and has come to the support of the Democratic ticket. Senator Goldwater talks of "strengthening" social security, which is an espousal of the Mills position. His Physicians for Goldwater Committee reads like a Who's Who of the American Medical Association, which has not been known to equivocate on Medicare. At the national level, the issue is clear.

The current Medicare strategy is, of course, based on a major Johnson mandate on election day, as well as a change in the composition of the House in the program's favor. Mills has held out for seven years, under constantly growing pressure. He probably cannot hold out much longer.