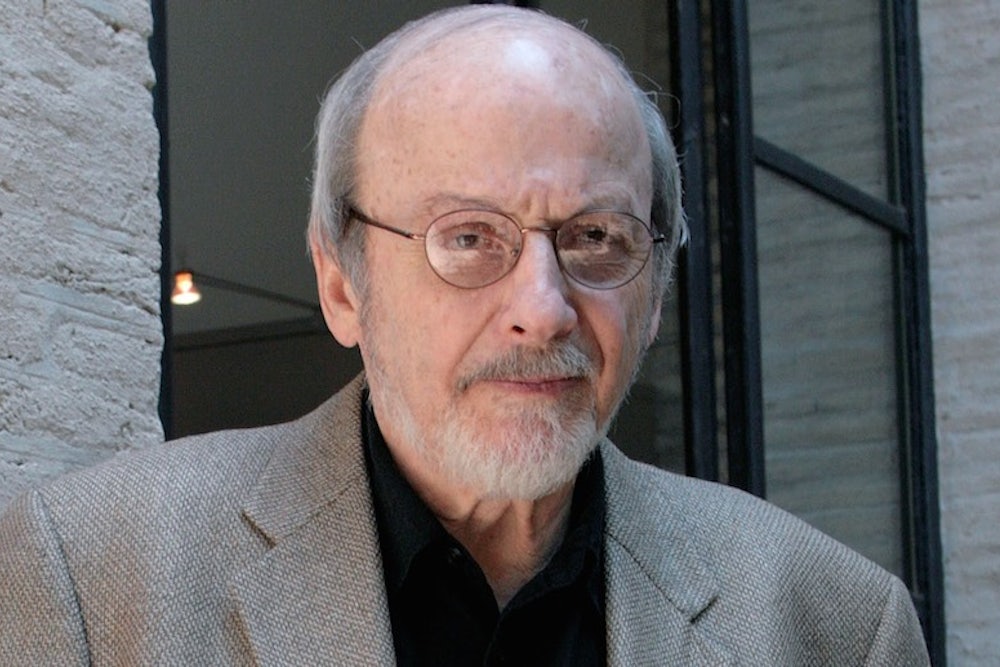

E.L. Doctorow, who died yesterday, wrote historical novels that never ran the risk of being merely antiquarian. The past was never really dead for Doctorow, but always connected to present-day realities. Doctorow himself was more than a fiction writer. He was a bridge to an older America, one that shaped the modern world in ways that were often willfully forgotten.

In his 1991 book Postmodernism, the literary critic Fredric Jameson wrote that “E. L. Doctorow is the epic poet of the disappearance of the American radical past, of the suppression of older traditions and moments of the American radical tradition: no one with left sympathies can read these splendid novels without a poignant distress that is an authentic way of confronting our own current political dilemmas in the present.”

A prime example of what Jameson had in mind was Doctorow’s The Book of Daniel (1971), about a 1960s student activist researching his parents, executed spies loosely based on Julius and Ethel Rosenberg. The Book of Daniel is much more polarizing than other Doctorow’s other novels—former editor of the New York Times Book Review Sam Tanenhaus dismissed it as “kitsch” on twitter yesterday—but it is central to his development as a writer. It was in The Book of Daniel that Doctorow discovered his great theme, the return of the repressed, the way the political movements that were crushed by McCarthyism in the early cold war came to the fore in other guises in the 1960s.

Doctorow’s historical vision was enormous in scope and bookended by two wars: the Civil War and the Vietnam War. His prime interest was the America that ran from Abraham Lincoln to Harry Truman, the America that crushed the Confederacy but left the problem of slavery unresolved, the America of mass immigration and industrialization, of labor unions and robber barons.

Doctorow’s fiction enjoyed its greatest vogue in the 1970s when his novel Ragtime (1975) was an enormous bestseller. It’s tempting but wrong to see Doctorow as an example of the nostalgia boom that overtook America during the 1960s and ’70s. This was a period when you could go see Grease on Broadway, American Graffiti in the movie theatre, and “Happy Days” on television. Dismayed by the Vietnam War and the Watergate scandal, Americans increasingly turned to pastoral celebrations of seemingly simpler times.

Doctorow actually had a role to play in the rise of the nostalgia industry. In the early 1960s, as editor at The Dial Press, he commissioned the publication of Jules Feiffer’s The Comic Book Heroes (1965), the first hardcover reprinting of such 1930s and 1940s caped crusaders as Sueprman, Batman, and The Spirit. The text of Feiffer’s book indulged in no good-old-days falsifications: It was clear-eyed in linking superheroes to the trauma of the Depression and World War II. Still, the success of Feiffer’s book inspired countless imitators, which robbed the artifacts of the past of their historical context.

Despite his role in sparking the nostalgia boom, Doctorow was in fact an anti-nostalgist in a nostalgic period. His books never shirked from describing the primordial conflicts over race and class that were the very foundations of history. It’s instructive to compare the movie The Sting (1973) with Ragtime. A sprightly caper film starting Paul Newman and Robert Redford, The Sting captures the look and feel of the Ragtime era, and helped spark a revival of popularity in the music of Scott Joplin, but has no ambitions to be more than entertainment. Everything that is forgotten in The Sting is remembered in Doctorow’s Ragtime. Among other things, the roots of Ragtime music in African-American culture aren’t forgotten in Doctorow’s novel, which includes one of the most harrowing accounts of racist humiliation in American fiction in the form of the story of Coalhouse Walker.

Doctorow’s substantial body of work—twelve novels and three story collections as well as a play and many essays—was uneven. Few would rank works like The Waterworks (1994) or City of God (2000) as important American novels. Yet Doctorow’s best work will live as classics.

Doctorow’s renovation of the historical novel, his ability to write about the past in a way that made electric connections to the present, expanded the range of modern fiction. His influence can be seen in such widely differing writers as Russell Banks, Susan Sontag, and William Kennedy. He wrote about the past but also changed the future of literature.