How do you break news if you don’t do all the sucking up required to get insiders to tell you secrets? Find the paper trail. Sometimes Gawker did that with Freedom of Information Act requests, but more often, it used embarrassing social media posts. Gawker’s greatest hits were morality tales about people accidentally screwing up their own lives with communications technology that hadn’t existed a decade earlier. Law & Order: The Internet. You have been found guilty of three counts of douchebaggery and your punishment is eternal Google poison.

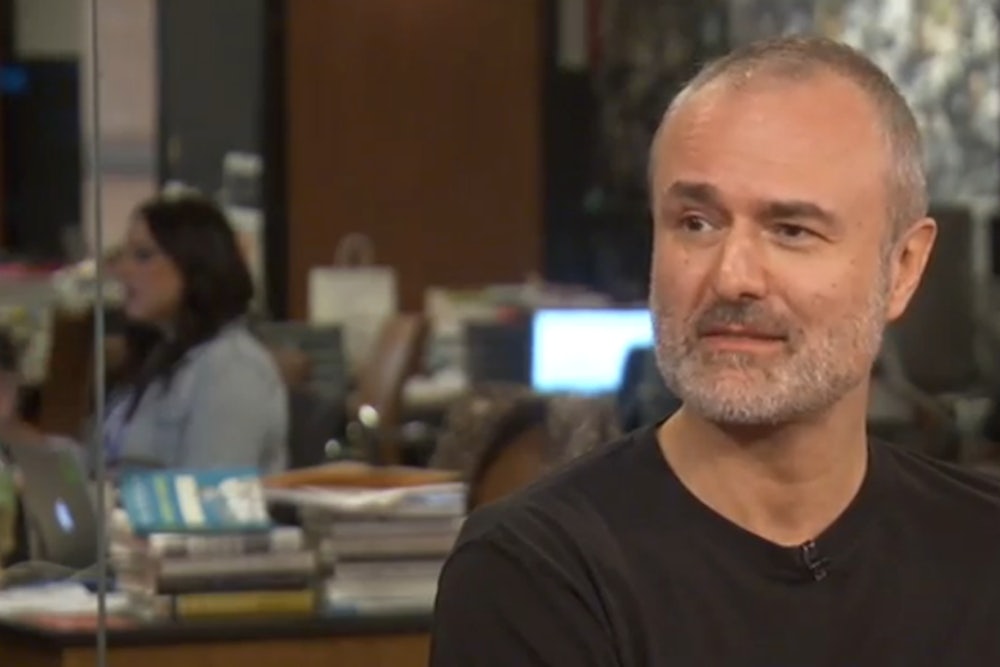

On Monday, two top Gawker staffers—executive editor Tommy Craggs and editor-in-chief Max Read—resigned over the deletion of a controversial post about a Condé Nast executive paying for sex. The decision to take down the story was made by a vote among Gawker’s managing partnership, not the editors, which, as explained by Gawker media reporter J.K. Trotter, “represented an indefensible breach of the notoriously strong firewall between Gawker’s business interests and the independence of its editorial staff.” In a memo, owner Nick Denton wrote of those who quit: “I respect the strength of your convictions. This is a decision you’re taking to preserve principles you believed I still shared.”

It feels like the end of something. But what? Of course it’s not the end of internet journalism, or adversarial journalism, or even Gawker. Instead it might be the end of the classic Gawker story. The post on the Condé Nast executive was a perfect example: a rich media person foolishly creating a digital record, complete with photos, doing something he presumably would not want the world to know about.

A few examples: A November 2007 post about a bank intern who lost his job because he called in sick but posted photos of himself partying on Facebook. A November 2008 post about two people having sex in their ad agency office, taped without their knowledge. A January 2013 post about the oil company employees who accidentally fowarded their sexy emails to the entire staff. A classic recurring column scoured New York party photos and mercilessly mocked the goofy-looking partiers and their outfits. It was called Blue States Lose, and it combined rage against hipsters and trust-fund kids with liberal anxiety in the Bush era.

Gawker launched in 2003 in a very distinct time in politics, an era when it felt like all of America had lost its mind. The rage against the press—and specific reporters—seemed to flow from that. To get deep in the weeds, take this comment by Ian Spiegelman, who had quit Gawker over a change in how writers were paid, on a 2009 post mocking The New York Times’ incessant coverage of rich people in the Hamptons.

It is by and large a newspaper by the rich, of the rich, and for the rich. Research who actually writes for them: mostly educated at eastern seaboard private schools; mostly had their student loans paid off by their parents, if they ever took any out in the first place.

The rich needed to be taken down, sure, but so did the less-rich-but-still-pretty-rich people who wrote so lovingly about them.

Often the targets seemed quite deserving. There was New York State Representative Chris Lee, who, in 2011, posted in Craigslist’s men-seeking-women section, complete with photos of his relatively buff torso and a description of himself as a “fun fit classy guy.” Lee, a married Republican, resigned after Gawker posted the photos.

But sometimes even public figures seemed undeserving of the Gawker treatment. In 2010, Gawker published a post titled, “I Had a One-Night Stand With Christine O’Donnell,” about the Delaware Senate candidate. It included photos of O’Donnell, looking happy and silly in a ladybug costume. The anonymous author admitted he did not actually sleep with the candidate when they met three years earlier—meaning the post wasn’t even evidence of some kind of social conservative hypocrisy on the Republican’s part. She was described as a “cougar,” and the author described her pubic hair, the existence of which was “a big turnoff.” The post basically portrayed O’Donnell as a sad single lady. It was not fighting the good fight.

You didn’t even have to be a public figure. You could be related to one—you would probably eventually go on to benefit from nepotism. A paragraph in a quaint 2006 Washingtonian story about Facebook neatly summarizes the threat faced by any youth with any tie to fame at the time:

For college-age children of celebrities, the Facebook can cause unwanted attention. Luke Russert, son of NBC’s Tim Russert and a Boston College student, got into trouble when Gawker.com picked up his Facebook photo—Luke in a hot tub surrounded by scantily clad coeds. The profile was quickly taken down. Phil Alito, son of Supreme Court nominee Samuel Alito, also had a profile up, blogger Wonkette revealed.

Gawker built characters—some against their will, some not (the “fameballs”)—and covered them almost as relentlessly as they would Tom Cruise or Dick Cheney. By the late 2000s, the media was experiencing full Gawker panic (we are now in the era of BuzzFeed panic), with long examinations of what Denton hath wrought. “The status of Gawker rose as the overall status of its subjects declined, and it was this that made Gawker appear at times a reprehensible bully. You could say that as Gawker Media grew, from Gawker’s success, Gawker outlived the conditions for its existence,” n+1 argued way back in 2008.

In 2006, a Yale student’s video resume caught the attention of Gawker, which named him the charter member of the “Douchebag Hall of Fame.” Gawker solicited “information on titanic douchebag Aleksey Vayner,” which got responses like:

I graduated in June and remember this [douchebag] talking way too loudly in the dining hall. In between powering whole chickens, he would high-five the smarmy, mustachioed dining hall managers and, in general, had the air of a slightly thick Afrikaner rugby player just chilling during apartheid. He also had atrocious arm acne.

You can feel the tipster straining to imitate the Gawker style, building an indictment out of relatively minor social infractions, such as engaging with workers in the school cafeteria. Everyone wanted to write like Gawker! Vayner was hounded by the internet and eventually changed his name. He died, at 29, in 2013. After Vayner's death, CNBC’s John Carney wrote:

Looking back now, I think its safe to say that Vayner was in some ways a victim of technological innovation. YouTube was less than a year old. The ability to include a link to a video on your resume was brand new. The rules for such things weren’t yet well-understood. Someone was bound to make an epic error in judgment. Vayner got to be that someone.

The rules are now better understood. What’s also understood is that everyone has embarrassing photos of themselves somewhere. Everyone has stupid party photos on Facebook, or nude photos on some forgotten flip phone, or stray comments on a random YouTube video, or Gchat transcripts that could indict you on far worse crimes than douchebaggery.

People used to sort of shrug—anyone dumb enough to put something embarrassing online deserves the epic humiliation that might come from it. But that sentiment is fading. Now we can look at someone like an outed Condé Nast executive and think, “That could be me.”