About fifteen minutes into Court, the debut film by director Chaitanya Tamhane set in the courtrooms of Mumbai, a police officer asks a judge what to do about a large group of people who had been arrested en masse for traveling in the handicapped compartment of a train. They had all plead guilty. Justice, most of us imagine, is something to be delivered with gravity and deliberation. Here in Mumbai, though, it’s brisk, unceremonious, and vaguely comic: Without a pause, each person is fined 500 rupees and sent away.

Tonally, this moment reflects the rest of Court, where justice is administered with a mixture of uncomfortable speed and nonchalance. The film is a black comedy of mildly absurdist proportions, and it depicts a world of harsh cryptic laws, where time repeats itself and the line of cases waiting to be heard is eternal. I called Tamhane to talk about Court, which opens at Film Forum this week. “I was inspired by visiting a lower court in Mumbai,” he said. “There was so much chaos and mismanagement that I saw a space for humor.”

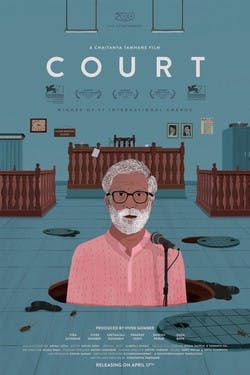

Court follows the arrest, trial, release, re-arrest, and re-trial of an elderly, leftist folk-singer, Narayan Kamble (Vira Sathidar), and the people who become involved with his case. He is initially charged with abetting the suicide of a sewage worker. The public prosecutor Ms. Natan (Geetanjali Kulkarni) and the police argue that his incendiary songs about the indignities inflicted by the rich upon the poor motivated a sewage worker to kill himself as an act of protest. Throughout the film, we see his defense lawyer, Vinay Vora (played by Court’s producer and financier, Vivek Gomber), struggle to wade through thick layers of antiquated laws, incompetent policemen, and overworked judges. It’s a state of affairs the film suggests is endemic to the Indian lower court system, and the judge, Mr. Sadavarte (Pradeep Joshi), presides over their arguments with an air of exhaustion.

The film is a welcome addition to critiques of the judiciary, from Bleak House to The Trial. Tamhane, who studied literature in college, confessed he did not make Court with Dickens or Kafka in mind, however—he focused on the plays of Beckett and Ionesco. “Film repeats itself at a point, and I was inspired for this structurally by these writers,” he told me. “It works so well because this case is absurd, but many left-leaning activists are repeatedly arrested on charges like this all the time.” Members of leftist groups like Kabir Kala Much, a source of inspiration for the film, are often arrested for promoting “terrorism” against the state and denied bail, as a means of stamping out activities deemed subversive and dangerous to the Indian people.

Though the singer Kamble is charged with violating several laws—some of which are residual English colonial penal codes—we get the sense he is really on trial for being a nuisance. His songs are too anti-establishment for some of his neighbors, the police, and the local government to comfortably tolerate. But Tamhane never produces a villain or a misguided idealogue as the root of this harassment. It’s something bigger than people that drives the plot against the elderly singer, but exactly what is difficult to see: Is it the government? The weight of colonial-era laws? Is it culture? Is it tradition?

Much of the film forgoes the traditional clash of political positions that legal drama is generally made of. There are no heroic stands against a biased jury, nor are there dramatic speeches, no mercenary lawyers to vilify or saintly ones to root for. Tamhane is too shrewd a director to have the rest of his characters stand merely as his protagonist’s opposition. Instead, he shows us a world where life and death decisions are given out with the same casual attitude with which one might file for a tax extension. At one point, when an anonymous woman is called for her case to be discussed, judge Sadavarte turns her away for dressing immodestly. She looks distraught, and her lawyer pleads Sadavarte to reconsider, but, for him, a dress code trumps any concern for a woman anxious to have her case heard.

“For me, the characters were the start of the film,” Tamhane reflected. “You or I might judge these people for stifling free speech, but the public prosecutor could be my mother, or the judge my uncle.” The public prosecutor Ms. Nutan, who argues against our proletarian hero, has as much screen time as her opponent. She’s a charming, sympathetic character: intelligent, practical, and, at times, warm. In short, human.

The film is deeply rooted in Mumbai, in its classes, culture, and history. Outside of the courtroom scenes there are no sets, and Tamhane, a native of Mumbai, clearly has a love for its buses, restaurants, apartments, and the bustling social interactions they facilitate. He uses these settings to illustrate just how different the daily lives are between the two characters on either side of the Kamble case: Vinay Vora, who is a young, rich, male lawyer from an affluent family, and Ms. Nutan, an older, middle class, female public prosecutor. A liberal audience will probably empathize with Vora, who is fighting for freedom of speech and the dignity of the oppressed. But his life—of solitary dinners in front of the TV, alienation from his family, and drearily hip clubs—is less charming.

“The film is about the city as much as it is about these characters,” Tamhane said. “In Mumbai you will find contradictions and diversities in social strata. I grew up seeing the clubs and bars as well as these plays and picnics I show in the film.”

Behind the visible conflict of youth and progressivism, embodied by Vora, versus age and conservatism, embodied by Nutan, there are several undercurrents of strife, some of which might be opaque to a western audience. “In the film there are four languages going on,” Tamhane points out. “There is English, the administrative language of India after 350 years of occupation, Hindi, the national language which everyone is supposed to know, Marathi the language of Maharashtra, which the prosecutor and judge speak, and Gujarati which Vinay Vora and his family speak.” Language is used as a subtle means of exclusion, a coded signal of group membership.

Xenophobia plays a significant role in drawing the lines between characters, a boundary that language helps draw. “You also have the caste system, which is playing an important but invisible role in the film,” said Tamhane. While the judge and prosecutor belong to the Brahmin, the highest caste, Narayan Kamble is a member of the Dalit (the lowest caste, the untouchables) community that has experienced thousands of years of oppression. “It’s a very important trigger," Tamhane told me.

Court is the result of a particularly fortuitous pairing of minds. Chaitanya Tamhane met Vivek Gombe while working together in an avant-garde play, Grey Elephants in Denmark. “After that I was pretty broke and depressed,” Tamhane recalled. “I wanted to develop this script but I didn’t have any money. There was a lot of pressure on me to take a normal job. Vivek saw how depressed I was when we met up again and on a whim he said ‘I’ll give you a monthly stipend if you finish this script.’” Originally Gomber had no intention of becoming a film producer, but the script impressed him enough for him to decide to finance the film himself.

Without relying on the language of wartime atrocity, of the supernatural, or of romance, it is surprising how well the film has been received internationally—winning awards in Venice, Singapore, and Hong Kong; it's being distributed by the prestigious Zeitgeist Films. Tamhane is delighted, and more than a little baffled. “We were quite sure at the beginning that an international audience would not understand the film,” he told me, “because it’s rooted very much in Indian culture, the languages and class politics, the idea of a people’s poet, xenophobic themes in theater.”

Before Court reached international audiences, the prospect of doing a film was daunting for the young director and producer. “A lot of people were like ‘What are you doing?’ because I was 25 at the time and had never worked as an assistant or made a feature before,” said Tamhane. Gomber, who was then 33, had never produced a film. Court is a testament to their talent and ambition. Most directors, even great ones, debut with shorter films set in easy to film locations with a small cast and crew. Court took three years to make, is nearly two hours, and was shot in a city of 18 million people with large ensembles of extras and a number of locations. When I asked how he achieved these effects, Tamhane said that Gomber helped carry out his vision for the film: “Everything I wanted, he made it happen.”

As of now, Tamhane is working on a another script. “But that’s something that gives me nightmares,” he joked. “I can’t really say for sure what it’s about as of now. I know it will not follow a linear narrative, and it will be nothing like Court.” There are few, if any, directors under 30 to have made something so beautiful and nuanced about something as large as the systemic injustice of the Indian court system; if his next film resembles his first, I hope it exposes the universal struggles found in specific political ones.