July is a sleepy time on the University of Vermont campus in Burlington, and ordinarily the basement of the Bailey/Howe Library would be sleepier still. However, in recent weeks it has been bustling—not with students conducting academic research, but outsiders conducting political research. They have all come with one purpose: to dig through the Bernie Sanders archive.

Some are national journalists, but others are more mysterious figures. A reporter for local alt-weekly Seven Days recently speculated that "two casually dressed twentysomethings" at the archive were opposition researchers for Hillary Clinton—which her camp later denied, though not before Drudge Report picked up the story. Ever since then, a retinue of young men has streamed through the library basement. They refuse to identify themselves, and the librarians on duty do likewise, citing Vermont privacy statutes and their own code of ethics.

These men work for Sanders's presidential campaign, the headquarters of which is a stone's throw away, and they have been tasked with digitizing the entire archive—a gargantuan effort that left the librarians flummoxed when staffers announced their plans last week. It's a vast trove of some 30 boxes of documents chronicling Sanders's eight-year mayoralty of Burlington and other early political activities. As material is not allowed to leave the special collections room, Bernie's workers sit for hours on end, scanning every last leaf of paper onto thumb drives.

They say little, but in a rare moment of candor, one did ask me whether I was “with Hillary." Otherwise they refuse to engage, operating under strict orders not to speak with media under any circumstances. Asked if these men are paid Sanders staffers, campaign spokesman Michael Briggs said, "Interns are staff, and staff are paid." Otherwise he declined to comment on their task, what prompted their arrival, or how many there are. Campaign manager Jeff Weaver said of them, “Just collecting information for ads and to document his record of effective leadership as Mayor of Burlington."

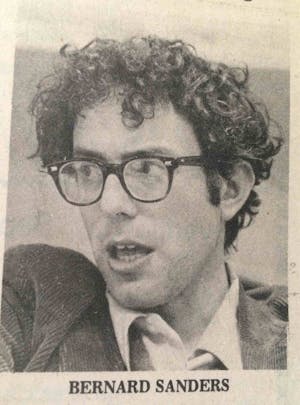

Sanders’s ad hoc 2016 operation in some sense is a reflection of the Vermont senator himself, who famously eschewed neckties until first entering elective office and reliably projects an image of rumpled earnestness. The campaign is powered thus far more by passion than structure, lacking the hyper-organized, corporatized polish of the Hillary Clinton juggernaut. Whatever the upsides of such an approach, the goings-on in Bailey/Howe Library suggest that the campaign might have been unprepared for the sudden surge of interest in Sanders’ past.

The digitization of the Sanders archive began about a week ago, and that his campaign apparently only thought to do so now could indicate a refreshing lack of paranoia. But it's potentially a tactical misstep, too. As much as Sanders might have evolved since his leadership role in the Vermont’s renegade Liberty Union Party during the 1970s, his records from that period are housed in the UVM archive for all to see—and might require a bit of contextualization from his campaign, lest an opportunistic opponent portray them unflatteringly.

Notwithstanding Politico Magazine's claim that "Bernie Sanders Has a Secret," no bona fide bombshells have emerged yet from the archive or elsewhere. Much of the material is fairly unremarkable to those schooled in Cold War-era socialist discourse, especially given that Sanders today is a self-identified democratic socialist. Nonetheless, his past statements could feasibly cause some disquiet among the culturally conservative working men and women whom Sanders hopes to court.

To wit: Sanders described himself as “clearly anti-capitalistic” in a 1976 interview with the Cynic, UVM's weekly student newspaper.

“Contrast what the young people in China and Cuba are doing for themselves and for their country as compared to the young people in America,” he said. “It’s quite obvious why kids are going to turn to drugs to get the hell out of a disgusting system or sit in front of a TV set for 60 hours a week.”

Television's enervating influence was a recurrent theme for Sanders in those days; in 1972, he wrote a letter to FCC chairman Dean Burch denouncing as “banal” such classic Americana as “I Love Lucy” and “Gunsmoke.”

“How many programs do we see which reflect what is really going on in this nation?” Sanders asked. “Where is the weekly T.V. network series which deals with the worker who is unable to find a job and who is drinking himself to death as a result?”

In the Cynic interview, Sanders was asked to expound on the nature of socialism, a question that continues to arise 40 years later. But in something of a departure from his typical response today, Sanders confessed ambivalence about the term’s connotations. "I myself don’t use the word socialism because people have been brainwashed into thinking socialism automatically means slave-labor camps, dictatorship, and lack of freedom of speech,” he said. “The [Liberty Union Party] more strongly than any other party in the State of Vermont defends civil liberties.”

That defense of civil liberties included a commitment to unfettered gun ownership: The party, while Sanders served on its executive committee, adopted a platform in 1972 that called for the “abolition of all laws which interfere with the Constitutional right of citizens to bear arms.” This may suggest that Sanders’s relatively permissive views on gun ownership, already the subject of much consternation among liberals, could be rooted in sincere principle—not simply in the practical realities of winning election in rural Vermont. While this position might irk the average Democrat, it could ultimately serve to broaden his appeal: Sanders has said he wants to forge a coalition that can “cross traditional liberal-conservative lines.”

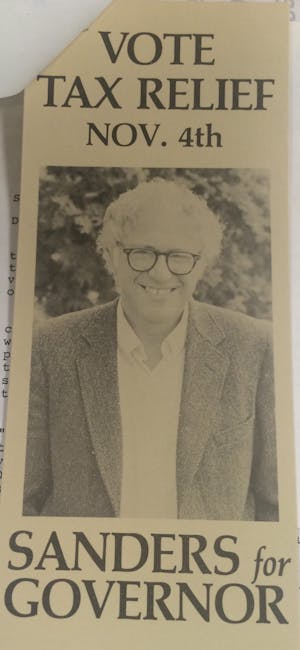

Other documents in the archive may help in that effort, such as those documenting his consolidation of municipal services as Burlington mayor, as well as his disdain for property taxes. During his Liberty Union years, Sanders endorsed the total elimination of “the very regressive property tax system,” to be replaced by a much more steeply progressive income tax. By his 1986 bid for governor, he had adopted “Vote tax relief” as a campaign slogan. You might even say he ran the municipal government as a fiscal conservative.

All of which is to say, there's a lot to mine in the archive, for both the good and ill of the campaign. Sanders, who did not respond to an interview request, probably has as little patience for discussing the contents of those 30 boxes as his campaign leaders do. But his small army of digital archivists have no choice but to be patient as they toil their summer away in a library basement—scanning, scanning, forever scanning. As I overheard one of them lament, “My grandchildren will be working on this.”