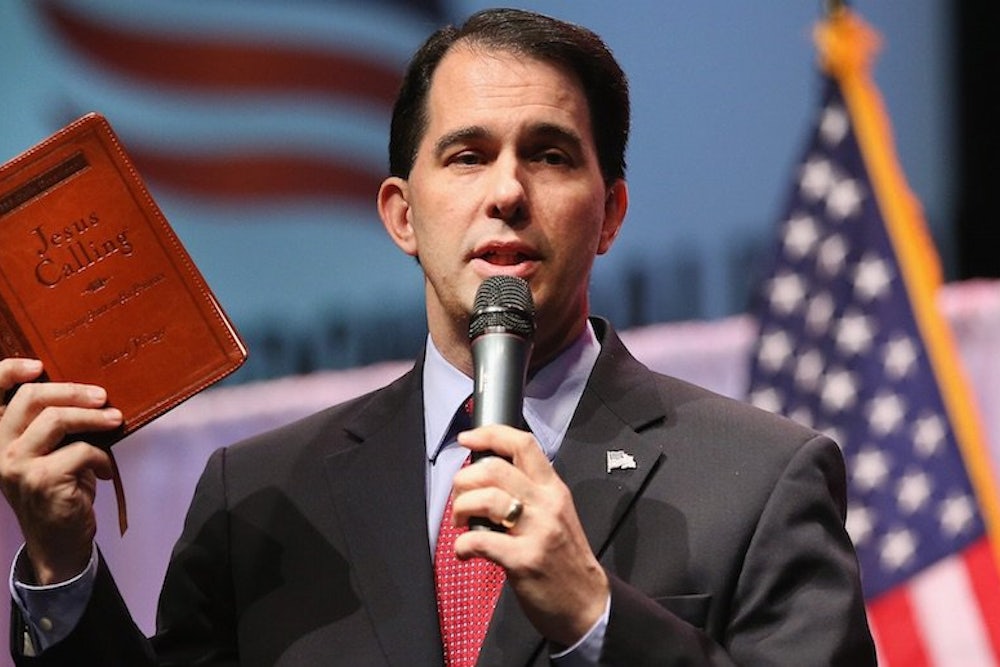

Wisconsin Governor Scott Walker is better known for his union-busting prowess than his evangelical faith, but in recent months he’s been talking more openly about the latter. And for good reason: his bid for the Republican presidential nomination may well rise or fall on whether he can persuade his fellow believers to rally behind him rather than, say, Mike Huckabee. Walker has fashioned a religiously resonant brand (“Our American Revival”) for his free-market gospel, and the early polls from Iowa suggest evangelicals buy it.

But if history is any indication, evangelicals' faith could complicate Walker's anti-labor stance. For as much as Walker sings the praises of neoliberalism, evangelicalism has often resonated with the conviction enshrined in the old Wobblie hymn: There is power in a union.

Evangelicals played pivotal roles in launching the American labor movement. Andrew Cameron—a Scottish immigrant, accomplished printer, and devout believer—helped to found the National Labor Union in 1866. The longtime Chicagoan went on to become internationally known for his advocacy on behalf of the (then controversial) eight-hour workday. For Cameron, organized labor was more than just compatible with Christianity; it was a fundamentally Christian response to Gilded Age capitalism, which, whatever the free market boosters said, was patently unfair. As he put it in an 1867 edition of the Workingman’s Advocate, his nationally-circulated labor paper, “Poverty exists because those who sow do not reap; because the toiler does not receive a just and equitable proportion of the wealth which he produces.” Cameron—who constantly quoted the Bible and never missed a chance to point out that Jesus had been a workingman—went to his grave believing that “the Gospel of Christ sustains us in our every demand.” He was hardly alone. Industrializing Chicago was a hub for pro-union Christianity.

In the early decades of the twentieth century, evangelicals such as James W. Kline held major leadership positions in the American Federation of Labor and its member unions. In 1911 Kline, then president of the International Brotherhood of Blacksmiths, traveled to San Francisco and was in the midst of heated strike negotiations when he received a telegram from his Bible class back home. It read in part, “God bless you in your efforts to do that for which the Master came.”

Throughout the Great Depression evangelicals, like many other Americans, poured into labor’s swelling ranks. Matthew Pehl has shown that, in Detroit, a number of African American religious leaders successfully persuaded their flocks to give organized labor—with its long history of racially exclusionary practices—another chance. Such breakthroughs keyed the United Automobile Workers’ campaign to turn Motor City into a union town. Meanwhile, in and around the Missouri Bootheel, Pentecostal-Holiness revivals propelled white and black sharecroppers alike into the ranks of the Southern Tenant Farmers Union (STFU). In his book Spirit of Rebellion, Jarod Roll points out that STFU locals often opened their meetings with prayers, hymns, and bible readings. Little wonder that one Arkansas farmer later recalled, “When they first started talking about the union I thought it was a new church.”

To be sure, this is not the whole story. Important books by Darren Dochuk, Bethany Moreton, and Kevin Kruse underscore that during these same New Deal years and on into the Cold War, corporate executives worked with leading evangelicals to baptize free enterprise as the best way forward for “Christian America.” But their success was never complete. In a deeply researched new study, Ken and Elizabeth Fones-Wolf show that even in the deeply conservative postwar South, the moral status of organized labor remained a live question. A number of believers insisted, in the words of one protest banner, “Religion & Unionism Go Hand In Hand.”

They still do, even among some present-day evangelicals—including members of Walker’s own nondenominational congregation. Meadowbrook Church in Wauwatosa, Wisconsin, will not be mistaken for the crusading Moral Majority of old. Its leaders may share some of the same conservative views, but they typically steer clear of direct political engagement. This commitment to quietism was sorely tested starting in 2011, however, when Walker’s assault on public unions stirred up dissension within the congregation. In the wake of their governor and brother in Christ signing the now-notorious Act 10 into law, some at Meadowbrook were infuriated, others elated. People on both sides of the issue called for their senior pastor, John Mackett, to weigh in, which he declined to do. Some left the church, but the trouble did not so easily subside. The fact that, as late as 2013, Mackett was still calling for his members to end the "turmoil" and "slander" and "name calling" suggests that pro-union sentiment at Meadowbrook was strong and persistent.

So don’t be fooled. Especially if the Walker campaign’s bid to consolidate support among religious conservatives succeeds, it may start to seem like evangelicalism and anti-labor are of a piece. The reality is that while union-busting may be the reigning GOP orthodoxy, it is far from settled gospel truth.