When your office has only glass walls, the elevator starts to look like a consolingly private space. Earlier generations knew it wasn’t: Anyone who’s thought about making an “elevator pitch” has capitalized on the elevator’s public nature, taking their chances in the fleeting common ground between executives and underlings. But if the elevator had something to do with upward mobility, it’s also a reminder of steep descent. On the way down at the end of the working day, the elevator is where you share reckless confidences, and it’s where you hear people saying the most abandoned and obnoxious things they can think of. Things like: “My garbage disposal eats better than 99 percent of the world.” Or: “Goldman fucking Sachs. Ever heard of it?”

These last seven words were supposedly overheard in the elevator at Goldman’s offices in 2012, and were duly documented in a tweet from the @GSElevator account.

1 [On cell phone]: Goldman fucking Sachs. Ever heard of it? [Click]

—

gselevator

The account, which was at that point anonymously run, offered a uncensored glimpse into the world of high finance, claiming to report from the firm’s Wall Street offices. It portrayed Goldman employees as self-obsessed, self-justifying, and misogynistic, as well as indifferent to the consequences of the financial crisis. Post-2008, @GSElevator gave its readers balm for their wounds: a chance to see bankers brought low. The account showed them miserable in their work too, griping in the windowless, WiFi-less elevators like everyone else. With over 700,000 followers, it is far and away the most popular specimen in a whole genre: the elevator Twitter account.

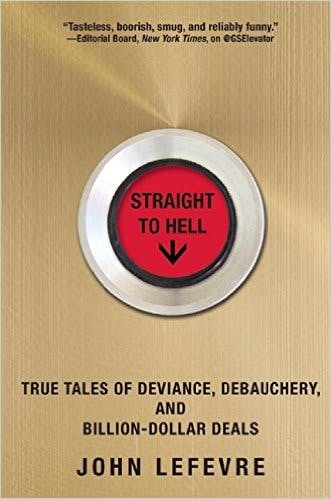

The man behind @GSElevator has now written a book, which expands on the banker lifestyle behind the tweets. With a bright red elevator button on its gold front cover, Straight to Hell: True Tales of Deviance, Debauchery, and Billion-Dollar Deals, out early next week, promises to transport its readers into the same chamber of secrets as the Twitter account. In fact, it brings us a little too far into the fold. Instead of a wry eavesdropper, its author emerges in the course of its 300 pages as a semi-insider, who might like to get a bit closer to the corporate culture he’s spent the last few years mocking. He got a job in a bank straight out of college—not at Goldman—and he later nearly worked at Goldman—but didn’t end up working at Goldman. As the book jacket complicatedly explains, he was hired in 2010 to head up “a debt syndicate in Asia,” but didn’t take the job “due to a contractual issue,” though what that might be is anyone’s guess.

There were early signs that the Bildungsroman-style memoirs of a wannabe Goldman employee might not have the same appeal as @GSElevator. Simon and Schuster had bought the rights to the book in January last year; it was important that at this point the identity of @GSElevator still wasn’t known. Once his name—John LeFevre—was revealed a month later in The New York Times, the publisher got cold feet, and they canceled the contract in March. It was now widely known that LeFevre didn’t himself ride the elevators of Goldman Sachs. Did that make his work less authentic? In an open letter he posted on Business Insider, he claimed a right to artistic license, arguing that “any person who actually thought my Twitter feed was literally about verbatim conversations overhead in the elevators of Goldman Sachs is an idiot.” He found a new publisher a few weeks later.

LeFevre’s defense of @GSElevator hit on the account’s major appeal. What made it so fascinating was that it could have been run by anyone. It took one of the more daunting aspects of corporate culture—its facelessness—and turned it back on one of the most high-profile firms as a weapon. LeFevre’s own lack of identity allowed him to perform a series of impersonations of Goldman employees convincingly and entertainingly, as though he’d been able to infiltrate a corporate culture that wouldn’t have noticed him even if he had actually been there. More than just making the point that bankers say awful things, he captured an atmosphere in which results were the only thing that mattered, to the near-complete exclusion of personal ethics. As a “curated” selection of tweets, reprinted in Straight to Hell shows, much of @GSElevator’s “banker humor” deliberately flouts social norms:

"Hot girls will never know if they are actually interesting or not."

—

gselevator

1: I am not inappropriate. You are just fucking boring.

—

gselevator

1: If you're not dead to at least one person, you're not living right.

—

gselevator

Other popular elevator Twitter accounts and “overheard in” accounts—Overheard Newsroom has over 100,000 followers and Overheard at NYU has a more modest 2000—reflect the same disconnect between big institutions and people who work for them. In an increasingly regulated and transparent workplace, the snatches of private conversation reported in their feeds are a much-needed injection of humanity. The short-lived Condé Nast elevator Twitter, @CondeElevator, for instance, only ran for five days in August 2011 but gained over 70,000 followers. Some of its best moments come when employees are confronted with the authority of the company’s most powerful executives, in this case Vogue editor, Anna Wintour:

silence] [silence] [silence] [silence] [silence] [silence] [silence] [silence] Summer Intern: "Was that...?" Intern #2: "Yeah" #annawintour

—

condeelevator

The silence is crowded out in LeFevre’s book by tales of inane deals and weekend festivities. (High on the agenda are beer pong and “Love Monkey Bowling,” which seems to involve aiming naked women—where did they come from?—at bowling pins fashioned from ketchup bottles.) The lonely brilliance of the elevator Twitter account doesn’t translate into book form, because it’s the contextless, unpredictable nature of the tweets that reproduces so exactly the contextless, unpredictable nature of so much work and things that get said in the last corners of private space at work. What a book does, by contrast, is provide context, and that, like those ketchup bottles, is too much information.