Tarsem Singh’s new film, Self/Less is billed as high concept sci-fi fantasy wish fulfillment. A super-secret scientific lab has developed a process whereby rich, ailing geniuses can have their brains planted in spanking new virile bodies. Imagine the possibilities! No more death; no more aging. With immortality available, how would the world change? What would you do if you could live forever?

These provocatively banal questions, though, are really just feints. Self/Less doesn't care about immortality. The dream on offer here is not the egocentric empowerment fantasy of eternal youth. Instead, Self/Less plumps for mushy humanism—which, as it turns out, is even more capitalist, and substantially more morally bankrupt.

The plot of Self/Less centers on Damian (Ben Kingsley), an aging genius developer with oodles of cash. Damian is a prick and a bully, but in a sympathetic, appealing way. We first see him using his political clout to ruin the life of an up-and-coming developer, but that's quickly forgiven since he has a buddy, Martin (Victor Garber), who thinks he’s nice. Best of all, Damian is dying of cancer. How can you hate someone who’s dying of cancer, especially when he’s played by Ben Kingsley? If Ben Kingsley played the Koch brothers, you’d like them too.

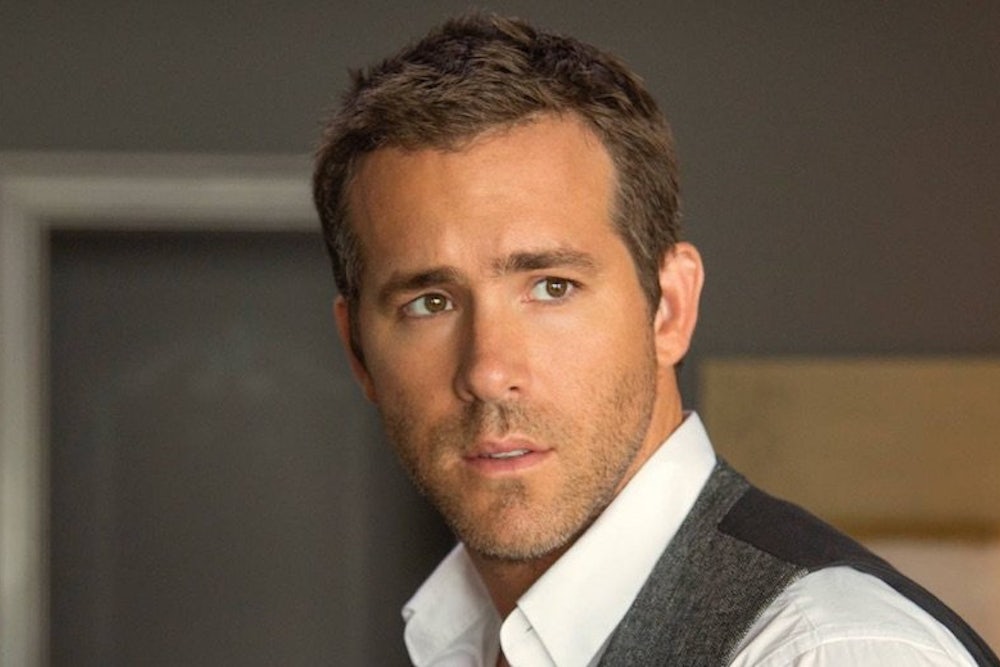

Damian doesn’t want to die, and the audience isn’t supposed to want him to die, either. So he spends millions for a new semi-experimental technique called shedding, which involves putting his brain in a young, hot, awesome body, played with maudlin indifference by Ryan Reynolds. The scheming Professor Albright (Matthew Goode) tells Damian that the Reynolds body was born in a vat, but it was in fact stolen from a working class guy named Mark who sold himself to science to pay for his daughter’s healthcare.

At first, Damian indulges himself in the way you’d expect an old, rich asshole would if he were suddenly decades younger. He plays sports, goes boating, and sleeps with a series of interchangeable conventionally attractive women who look like they’ve all answered the same Hollywood casting call. The one downside is that he has occasional hallucinations. To keep them in check, he has to take red pills on a careful schedule. But when Damian is too busy using his genitals and misses a dose he has a series of flashbacks to Mark’s past life. Soon he’s reconnecting with Mark’s wife and daughter—Madeline and Anna—while fighting the corporation that gave him his new body.

This remains an action-adventure fantasy to some degree. Mark was in the army, and so Damian finds himself with unexpected badass skills. As with The Bourne Identity or Total Recall, another amnesiac everydude discovers he’s a superspy. Identification as empowerment couldn’t be more blatant.

But the real energy in the film is devoted to Damian’s salvation. The audience stand-in here isn’t just an audience stand-in; he’s a super-rich jerk. But, the film insists, super-rich jerks aren’t so different from you and me. They want to play basketball; they want to screw thin women. More than that, they care about injustice and would rescue the downtrodden if only given the chance. Damian has a crappy relationship with his daughter, Claire; he was never around during her childhood and sneers at her do-gooder non-profit job, all while trying to buy her affection with his checkbook.

But Madeline and Anna are a chance for the unfeeling corporate asshole to redeem himself. Damian pities them, he worries about them, he fights and kills for them. In a heartwarming scene, he teaches Mark’s daughter Anna (Jaynee-Lynne Kinchen) how to swim while she quips adorable one-liners. The capitalist may have ruthlessly appropriated the workingman’s body, but in doing so, he is humanized. Exploitation, through a somewhat confused calculus, leads not to class war, but to moral transformation. It's Marx as interpreted by Walt Disney.

This isn’t really a dream of living forever. Instead, it’s a dream that the rich don't actually want to suck the life out of you. If mortgage lenders just knew the people they were scamming a little better, the financial crisis would never have happened; if oil executives could only live with poisoned groundwater for a week or so, they’d stop fracking. At one point, Damian is forced to admit that he wouldn’t have helped Mark if the poor guy had just approached him for a check; but the up-close experience of being Mark changes his mind and makes him a better man. Workers and capitalists don’t really have different interests, Singh’s film suggests. It’s just that they are separated by a forgivable—and transcendable—failure of compassion. If the boss could imagine himself as the worker, he'd want to help that worker out. And, conversely, if the worker only really knew his boss, he’d be happy to have his wife, his daughter, and his life directed by the kind, benevolent paternalist, who has the ruthlessness to win and the ability to make tough choices. The rich love you, Self/Less says, and all they ask in return is that you love them back while surrendering your autonomy.

The film, then, isn’t about losing a self, so much as it’s about insisting, with a particularly American optimism, that all selves are the same. Some critics have dinged Ryan Reynolds for not even trying to mimic Kingsley’s mannerisms—but the whole point of the film is that mannerisms don’t matter. Everyone might as well be everyone else. Our hearts are the most important part of us, and those hearts all throb to the same gushy melodrama. Damian’s interests and moral journey are seen as universal. Self/Less should be called Class/Less, and its tagline should read: “The rich white guy is everyman.”