Cheated and disrespected, a black woman on film enacts bloody vengeance using her cunning, her ruthlessness, and the fact that society compulsively underestimates her. The final scene shows her expressionless—perhaps traumatized but unbowed, a survivor who has overcome abuse and humiliation and seized justice on her own terms. A black woman, for once, in pop culture, is the hero, and the avenger, of her own story.

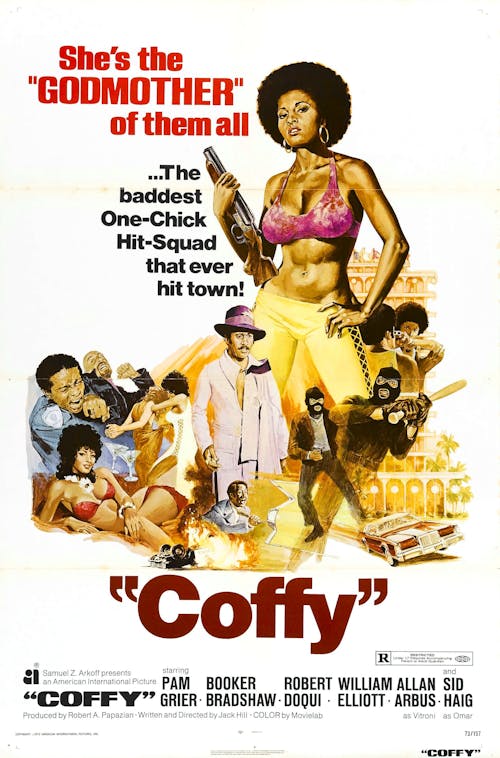

That describes both Rihanna's cinematic new music video, the self-directed "Bitch Better Have My Money," and its most obvious precursor, the 1973 film Coffy, directed by Jack Hill and starring Pam Grier in the title role. The blood-spattered "BBHMM" has drawn comparisons to Quentin Tarantino, but he's a huge fan of Grier and Hill: His 1997 film Jackie Brown, which also starred Grier, would not exist without Coffy, the first Blaxploitation movie featuring a female star—a watershed in the genre, and in Grier's career.

In the seven-minute "BBHMM," Rihanna kidnaps the wife of her accountant, tortures and possibly kills her, then murders the accountant as well, all to (successfully) get back money they stole from her through financial shenanigans. In Coffy, meanwhile, Greir's character launches a war on the drug trade to revenge her sister, who is semi-comatose after OD'ing. She escalates her vendetta when her childhood friend and would-be suitor, who also happens to be a cop, refuses to go on the take and is beaten almost to death by his fellow officers. Rihanna's video picks up on many of Coffy's tropes, including the innate political charge of seeing a black woman destroy her oppressors. But it also shies away from that revolutionary message and instead emphasizes individual triumph—symbolized, most vividly, by money.

Rewatching Coffy after "BBHMM," I can see why its blueprint endures today. Grier is not precisely a great actor, but her very awkwardness gives her a riveting verité. She comes across as knowingly sexual (pouring wine on her lover's penis as a prelude to a blowjob), street smart (the film lovingly shows her wrapping a coat around her off-hand for a knife-fight), and painfully vulnerable. Rihanna doesn't have Grier's range, though she captures some of Coffy's improvisatory smarts in one of the video's first scenes. As Sunny Singh points out at Media Diversified, Rihanna stands innocently in the elevator as her white target enters, ignoring her; this invisibility of a woman of color to a white woman enables Rihanna to get close to and seize the oblivious woman for the purpose of revenge.

There are echoes in that scene of the way Coffy plays on her opponents' expectations, as when she pretends to want one last sexual fling with gangster Omar (the always amazing Sid Haig) before he kills her. Omar believes her, because he believes black women always want sex. Blinded by his lust and his racism, he lets his guard down, and Coffy stabs him in the throat; the camera mercilessly follows him as he staggers about, pleading futilely for his thuggish companions to help him as he bleeds out.

The bloodshed in "BBHMM" is considerably less grotesque; it occurs off-screen, sans screaming, and is conveyed with stylized blood splatter. This reflects a broader difference between the two films. Coffy, with Roy Ayers funky, urgent soundtrack, is a low-budget, scruffy, ground-level look at a world of banal drug dealing, prostitution, and corruption. Rihanna's European-trance track, on the other hand, serves as a background for conspicuous consumption: Rihanna and her crew on a yacht, hanging out at poolside, and generally luxuriating in the perks of superstardom. When Coffy wants to cut someone, she hides razor blades in her Afro. Rihanna, for her part, has a luxurious array of fancy torture instruments; even her viciousness is high-end.

Mia McKenzie at Black Girl Dangerous argues that "BBHMM" is a politicized statement in that it shows "a black woman putting her own well-being above the well-being of a white woman"—the video is revenge for a history in which white women's needs, bodies, and souls are seen as more valuable and important than those of black women. You could also argue that Rihanna is referencing a long history in which black entertainers have been systematically ripped off by white music executives—and an even longer history in which black women's labor has been stolen by white people. The final, already iconic image shows Rihanna in a box covered in blood and cash. She's taking back blood money.

It doesn't take much of a leap to get to these political readings. Still, the surface narrative itself is important—and that narrative has Rihanna inhabiting tropes from gangsta rap, reveling in violence against a woman and in material success and power. It's possible to read the ending as suggesting that Rihanna killed her friends as well, since she's alone with the cash and the blood. In any case, her actions are presented, most directly, in the context of a personal economic vendetta. Her triumph is individual.

Coffy is much less ambiguous about its commitments. Coffy's duplicitous black boyfriend, the would-be Congressman Howard Brunswick (a virilely oleaginous Booker Bradshaw), reveals his corruption in a speech that places money above political solidarity. "Black, brown, or yellow—I'm in it for the green! The green buck!" he declares. Howard is a hypocrite, but his discussion of how the drug trade funnels money mostly to wealthy white people—including corrupt officers—is largely borne out by the narrative. Police commissioners, thuggish cops, and white, vocally racist crimelords work together to bleed African-American communities. Coffy fights, explicitly, on behalf of her family and her people. The fact that Howard, the race man, has betrayed those people doesn't negate the need for his analysis. It just means that Coffy needs to exact revenge on him too.

At the conclusion of the film, Coffy almost forgives Howard—but his white girlfriend inopportunely appears, and so she shoots him in the groin. Men, Hill and Grier suggest, will betray you for money, for sex, and just for the hell of it. If there's going to be liberation or justice, as Coffy makes clearer even than "BBHMM," black women will have to deliver it.

Correction: A previous version of this article referred to Sunny Singh as Sandra Singh.