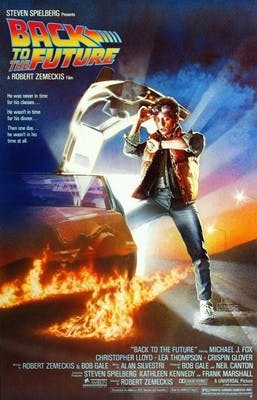

I didn’t realize until I was a little bit older that what we all saw thirty years ago this week in Back to the Future was a sexual assault, but I recognized the hero moment immediately. When George McFly opens the car door to find bully Biff Tannen with his hand up Lorraine Baines’s dress, he is shaken, but doesn’t move. Despite Biff’s attempts to scare him into leaving, George stays. “Are you deaf, McFly? Close the door and beat it,” he says. George stands firm. “No, Biff. You leave her alone.”

George doesn’t save the day with his weak punch that Biff immediately blocks, nor the more powerful one he later uses to knock out his tormentor. He takes a moment to savor the victory over Biff, but George’s real evolution comes when he stops the assault. I recall getting the message immediately, understanding that I’d watched George stop an attempted rape. I didn’t know the term “bystander intervention,” but I knew what it looked like to see someone do the right thing.

As a kid just out of the fourth grade, I learned from that Back to the Future scene that it was the responsibility of boys and men to stop sexual assaults and rape. But given how that the scene is set up in the film, I wish we could go back in time and make it vanish.

Back to the Future’s 30th anniversary gives us a chance to see why it’s worth reflecting on how deeply popular culture can root itself inside of us, particularly with regard to our attitudes about race and sex. We can continue to indulge in the delights of our childhood, but they’re also worth taking seriously. While I appreciate the generically positive representation of the film’s black characters, I cannot say the same for how it depicted women and the violence visited upon them. Today, I can’t feel good as a feminist about how we saw George’s vindication come about.

Few movies geared towards children and young adults in the 1980s came without a heavy-handed message. The apotheosis of this preachy genre was ABC’s Afterschool Special, which began in the previous decade and hit their stride in the Reagan era. And even if they embodied the ’80s in their obviousness and tacky dialogue, they were damned effective. Thirty years on, I still can’t shake the image of a drunken Val Kilmer running over Mare Winningham in “One Too Many.” These stories may have hit with a sledgehammer, but they worked.

Back to the Future, even in the assault scene, does this kind of messaging more subtly: The only mantra, spoken by several characters, is “If you put your mind to it, you can accomplish anything.” The review written by the late Roger Ebert points out that the film shares a lot with It’s a Wonderful Life—a man’s family life is changed by magical means. But Michael J. Fox’s aspiring rock star, unlike James Stewart’s family man, is merely a catalyst for the other characters’ personal development. Marty McFly’s big moments don’t involve him changing much: He achieves his dream of playing at the school dance, albeit in 1955, when he supposedly inspires rock-and-roll innovator Chuck Berry (and in the process, serves as a metaphor for the white perversion of black music). Marty goes back to the future, and saves the life of his true father figure, Doc Brown. But part of the movie’s conceit is Marty’s constancy in a constantly changing universe, the fact that he doesn’t really change at all.

Marty arrived in a pivotal year, as it turned out. Even though Back to the Future is set in a small northern California town, Marty travels 30 years back in time to 1955, the same year that Emmett Till was lynched in Mississippi. As a PG-rated ’80s sci-fi comedy with a nearly all-white cast the racial realities of Jim Crow aren’t addressed too explicitly, but it is notable that director Robert Zemeckis made sure that the most self-assured people in the film are the few black people who show up in Hill Valley. In a story that primarily centers on fostering one’s own self-confidence, it meant something to me as a boy to see the only folks who looked like me not backing down from anyone or anything.

While the film surely underplays the slights these black men would have likely suffered, those characters aren’t depicted as the archetypal Magical Negroes, either. The band that plays at the Enchantment of the Sea dance, Marvin Berry and the Starlighters, coolly intimidates the white toughs who call them “spook” and “reefer addicts.” That means more to me 30 years later, when too many Hollywood stories still treat black folks and their lives like racial wallpaper or indulge in stereotype. (The film doesn’t get it all right, indulging in the brown enemy of the day: The Libyan terrorists who seek revenge on Doc Brown, spouting Arabic-sounding gibberish.)

But in Back To The Future, the black busboy and future mayor Goldie Wilson is just an avatar for progress; George, in finally standing up for himself and for Lorraine, is the only character allowed to actually progress. But his evolution comes at the expense of pain suffered by the principal female character, whose only positive changes in the new 1985 are reflected exclusively in her weight loss and lack of drunkenness. It sticks out as a mistake and an opportunity missed.

While the final outcome is great for George, what about Lorraine—who, thanks to her son’s trip back in time, is now a sexual assault survivor? The last-ditch scheme to get these two to fall in love, to which George signs on, involves Marty sexually assaulting his mother, Lorraine, so his father can be the hero. (“You come up, you punch me in the stomach, I’m out for the count, and you and Lorraine live happily ever after,” Marty tells George, planning his hero moment.) But of course, he can’t go through with it—and is summarily replaced by Biff, who leaves Marty with his thugs and goes through with the molestation himself.

My memories of Back To The Future mostly come from the videotape I received in my grandparents’ dining room in the autumn of ’85 for my tenth birthday. It was unlabeled, and it was clean; no scratches on the tape, and no silver “HBO” slowly drifting through space during a Saturday Night Movie intro. I knew Grandma and Granddad didn’t get HBO or any other pay movie station—no commercials!—and neither did I. Bootleg movies of this quality weren’t available in plenty as they are in today’s barbershops and on various websites. It took effort to get. To a 10-year-old kid who loved movies and didn’t have premium cable, this showed love.

I learned to use a skateboard, poorly, because of Marty McFly. I later took up guitar, briefly, inspired by Marty’s Johnny B. Goode scene. The film’s messages weren’t as clear to me then, and I mostly loved it for the cool, Spielbergian way it presented the very nerdy idea of time travel. I loved how it played with the notion of alienation, most obviously when Marty arrives in the ’50s as a Devo-suited invader in the spaceship DeLorean and manages to assimilate into the retro teen reality. I also enjoyed the hilariously awkward way the film explored getting to know your mom and dad as real people before your birth and to see them fall in love. But in the revised future, Biff—Lorraine’s assailant—is portrayed as a mere functionary in the love story, and is shown waxing the family car in the driveway and later, coming inside the house to deliver a box of George’s novels. Lorraine is not so much a character as a device, denied all agency.

Those movies in the ’80s with a message made things easy. While I once regarded George’s breakthrough in Back to the Future solely as a great thing, a pop-cultural moment that helped point me towards feminism as a young boy, I see now that it came cheaply. Doing the right thing is so easy when all you have to do is be the hero.