After breakouts of measles and pertussis, two childhood diseases that should have long ago been relegated to history books, California welcomed a new law yesterday that bans personal and religious exemptions to vaccinations, allowing only medical exemptions, like allergies, to exclude a child. In signing the bill into law, Governor Jerry Brown brought his state in league with only two others that have limited vaccine exemptions to medical causes, Mississippi and West Virginia. And so far, Mississippi and West Virginia’s laws have been treating them pretty well.

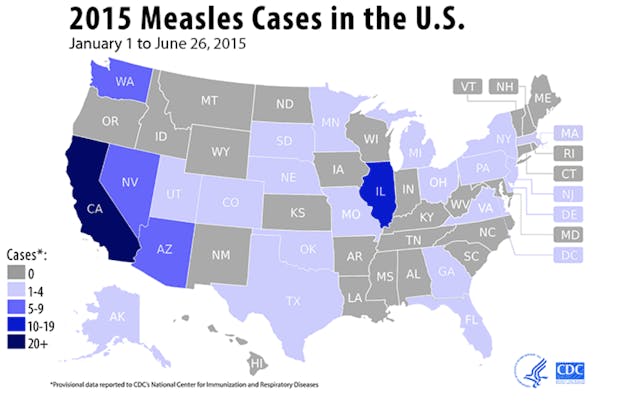

From January 1 to June 26, the Centers for Disease Control tracked confirmed reports of measles outbreaks state by state. Measles, an infection that can lead to permanent hearing loss, brain damage, and death, was conspicuously absent in West Virginia, despite clustering in surrounding states:

Mississippi, too, reported zero cases. On the pertussis front, both states also report encouraging numbers. During 2014, Mississippi had 2.3 cases of pertussis for 100,000 people, while West Virginia had 0.9 cases per 100,000. These numbers were among the very lowest of all 50 states. What these numbers reveal is that a state does not need to be especially wealthy or especially suffuse with high-quality healthcare access to protect children from childhood diseases. It just needs to require children to receive vaccines.

Why would anyone opt out of one of modern medicine’s finest achievements? Reasons vary. Americans have an intensely individualist streak, which disinclines us from recognizing the communal benefits of programs that are essentially community-based, like vaccinations. There is also a certain level of mistrust of vaccines among some of society’s upper echelons, spurred on by now-disproven claims that vaccines cause autism or other illnesses, and undergirded by a general taste for the natural and organic. This is the stuff of “personal exemptions.”

California Gov says yes to poisoning more children with mercury and aluminum in manditory vaccines. This corporate fascist must be stopped.

—

jimcarrey

But the world of religious anti-vaccination rhetoric is perhaps even more disturbing. This year, Dr. Paul Offit, a longtime advocate of vaccines and professor of vaccinology, published Bad Faith: When Religious Belief Undermines Modern Medicine, to explore and respond to those who refuse vaccines for religious reasons. Offit’s book is populated mostly by Christians: either members of the Church of Christ, Scientist, who refuse medical treatment in favor of prayer; or assorted Christians with a general mistrust of mandates and rabid belief in their absolute sovereignty over their children. “America was founded as a safe haven for religious beliefs that weren’t tolerated elsewhere,” Offit observes. “Unfortunately, the American public’s instinctive tolerance for religion often exceeds reason.” With concerns about religious liberty rising among conservative American Christians, one wonders if this brand of reflexively anti-authoritarian behavior will increase.

If more Christian parents now resist state laws compelling vaccinations through whatever exemptions are available in their states, it will be for these political reasons, not for legitimately religious ones. As Americans we are generally hesitant even to discuss whether or not a religious objection makes sense within the context of a faith, but in the case of vaccines, the case is fairly clear to me—and at any rate, children’s lives are on the line.

Parents who identify vaccination as a personal choice made for themselves and their own children misunderstand vaccination as a concept. Most people will survive childhood illnesses without the aid of a vaccine; vaccines are not administered on behalf of these people, though they do help them avoid the non-lethal downsides of disease, such as temporary discomfort and long-term injury. Vaccines are rather administered on behalf of people who cannot receive them, and people who would not survive the illnesses they protect against based on deficits in their own immune systems. These people include the very old, the very young, and those already suffering: people with HIV/AIDS, people going through chemotherapy, pregnant women, and people who have never had strong defenses of their own. Widespread vaccination of healthy people creates “community immunity” or “herd immunity,” which prevents illnesses from penetrating groups where vulnerable people live, thus saving their lives.

Vaccination is not only an individual healthcare choice, but a decision to participate in an act of self-sacrifice for one’s broader community. In most cases, the sacrifice is exceedingly small: a little bit of soreness at the injection site, and at worst, a day or so of feeling lousy. But it is worth it, in Christian terms, to protect the vulnerable. As Eula Biss writes in her 2014 essay collection On Immunity: an Inoculation, “the unvaccinated person is protected by the bodies around her, bodies through which disease is not circulating … the boundaries between our bodies begin to dissolve here.” Biss is right to note the similarity between this porousness of self and the narrative of the Gospel: “Jesus offering his blood that we all might live.”

Aside from contributing to a sharing of health, vaccination also communicates a message: Your life is worth living. It is the kind of act performed out of the belief that, yes, you are your brother’s keeper (a matter raised by Cain in Genesis 4:8 and revisited often later in scripture, including in Romans 14) , and that loving others as oneself (one of the two greatest commandments, according to Christ) requires a willingness to consider the life of another as equal to your own. There is an assumption of risk in vaccination, and the sacrifice of some comfort, but there is also a sacrifice of sovereign individuality, that uniquely American ideology that has so little in common with Christianity, even when the two aren’t in direct confrontation.

Christian parents are right to give plenty of ethical consideration to vaccination. But the case appears to me to come out squarely in favor of getting the shots, in accordance with laws like California's. Compared to all of the other ways in which Christians are obligated to sacrifice for others, a needle pinprick and few hours’ soreness are relatively minor. And if Christian parents are moved to wonder at what it means to use one’s child, inter alia, as a way to save others: all the better. That is, after all, one of the great mysteries of the Christian faith.