As the most senior Supreme Court justice inclined to support marriage equality, Anthony Kennedy enjoyed the right of first refusal to author the Court’s opinion in Obergefell v. Hodges; and as the only conservative on the Court willing to take the constitutional leap, the fate of marriage equality apparently hung in a precarious balance.

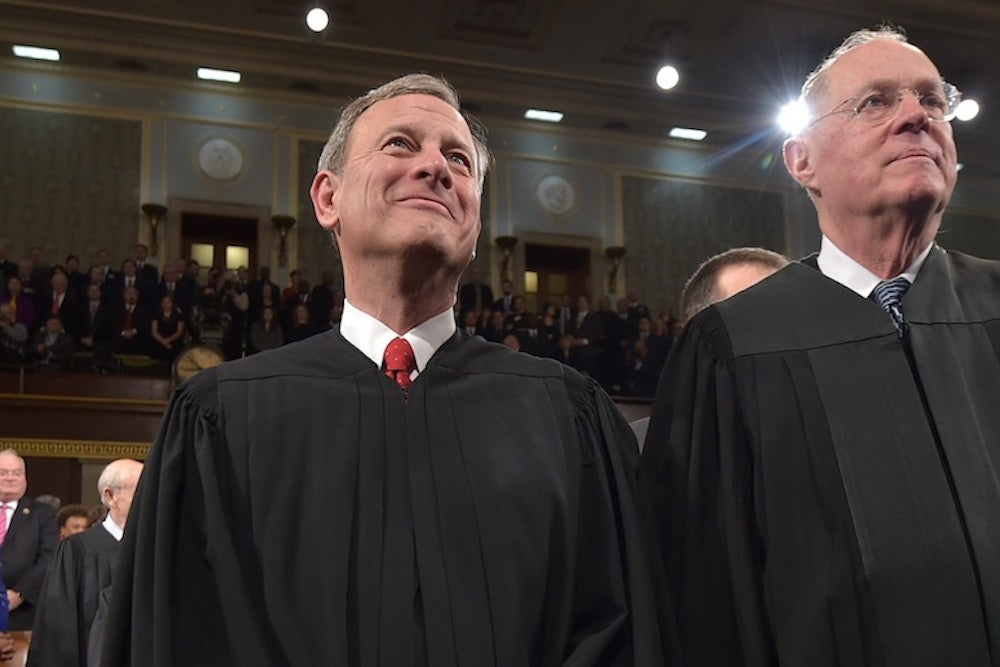

Under a less fragile arrangement, the ruling probably would have looked much different. Chief Justice John Roberts wrote the Court’s 6-3 opinion in King v. Burwell—and it shows—but it also reads like a consensus document that was circulated among its five co-signers, each of whom enjoyed fair input.

Kennedy’s Obergefell ruling is nothing like that. He succeeded in crafting a few poignant passages about the struggle for and righteousness of equality. And, of course, his ultimate holding was the correct one. But the price of admission for the Court’s four liberals was to join a muddled, unconvincing opinion.

Outside of academic specialties, historic Supreme Court decisions aren’t generally taught as logical treatises, but as watershed moments, which is great news for Kennedy because his opinion in Obergefell is, logically speaking, kind of a disaster. On those rhetorical merits, Chief Justice John Roberts completely outmatched him. Which is too bad, because a decision as solemn and momentous as the Court made Friday ought to hold up well not just as a historically impressive step, but a convincing one as well. A win is a win, but in this particular victory lies a reminder that liberals should make getting a fifth liberal justice on the Court an overriding priority.

As both a moral and legal issue, arguing for marriage equality (or, equivalently, for government neutrality on marriage) should be fairly easy: States and the federal government recognize a contractual situation called marriage, and through that recognition flows vague public sanction, manifest through real, tangible, legal preferences. The best constitutional argument for same-sex marriage is that the state can’t deny those benefits—conceptual or concrete—to gays and lesbians on the basis of their sexual orientation, or only bequeath them to gays and lesbians who are willing to enter into marriage contracts with people of the opposite sex whom they don’t truly love.

Kennedy alluded to the existence of an equal protection argument, but, as Roberts wrote in his dissent, “The majority [did] not seriously engage with this claim. Its discussion is, quite frankly, difficult to follow.” Roberts is correct. Kennedy failed “to provide even a single sentence explaining how the Equal Protection Clause supplies independent weight for its position.” This was Team Marriage Equality’s strongest ground, and Kennedy surrendered it against a mostly unarmed adversary. In the end, Roberts offered the Court’s only real equal protection argument (or counterargument) and it was weak by necessity. “[T]he marriage laws at issue here do not violate the Equal Protection Clause, because distinguishing between opposite-sex and same-sex couples is rationally related to the States’ ‘legitimate state interest’ in ‘preserving the traditional institution of marriage.’” This is another way of saying that gays and lesbians aren't deserving of the same kind of anti-discrimination protections the courts accord women and minorities. He was able to assert this without qualification, because Kennedy didn't force him to justify it.

A more nimble intellectual combatant would have made Roberts work for that ground. Roberts went on to suggest that the above-mentioned benefits of marriage could flow to same-sex couples through a separate-but-equal state-sanctioned institution, glossing over the fact that opposite-sex marriage triggered the benefits in part because states prized straight couples over gay ones. "Although they discuss some of the ancillary legal benefits that accompany marriage, such as hospital visitation rights and recognition of spousal status on official documents," Roberts wrote, "petitioners’ lawsuits target the laws defining marriage generally rather than those allocating benefits specifically. The equal protection analysis might be different, in my view, if we were confronted with a more focused challenge to the denial of certain tangible benefits. Of course, those more selective claims will not arise now that the Court has taken the drastic step of requiring every State to license and recognize marriages between same-sex couples."

At this juncture, Kennedy’s views about the intangible benefits of state recognition—the notion of dignity at the heart of his opinion—would have been useful, but he deployed them instead to argue that the right to same-sex marriage exists silently in the Constitution, essentially independent from the existence of a right to marry more generally.

"These [guaranteed] liberties extend to certain personal choices central to individual dignity and autonomy, including intimate choices that define personal identity and beliefs," Kennedy wrote.

I appreciate his sentiment insofar as it reflects the view that theres' nothing inferior about being gay. Or insofar as it stems from a desire to recognize same-sex couples’ right to marry—not as a belatedly and grudgingly acknowledged outgrowth of the right to opposite-sex marriage, but as something that’s been lurking invisibly in the constitutional ether for over a century, and has only recently been discovered. As a legal argument, though, it isn’t persuasive.

Nobody familiar with Kennedy’s jurisprudence was surprised by the tack he took, because he wrote many of his own precedents, including Lawrence and Windsor, all of which dance around the notion that straight and gay couples should be treated equally. For that reason, it doesn’t have the persuasive intellectual force that it could.

With respect to marriage, this may ultimately be a question of purely academic interest. Same-sex couples will soon be legally recognized across the land, as they should be, and the legitimacy of their right will probably hinge less on the logical forcefulness of Kennedy’s opinion than on the public’s rapidly shifting views about marriage itself.

But as long as Kennedy is the Court’s “swing” justice, he will frequently be the liberal justices’ best hope for good outcomes, and they will feel compelled to defer to him, even if he’s unable to marshal arguments that stand the test of time. Liberals can't do anything about that unless they're positioned to eventually replace a conservative justice—perhaps Kennedy himself—with a liberal. And that means winning elections.