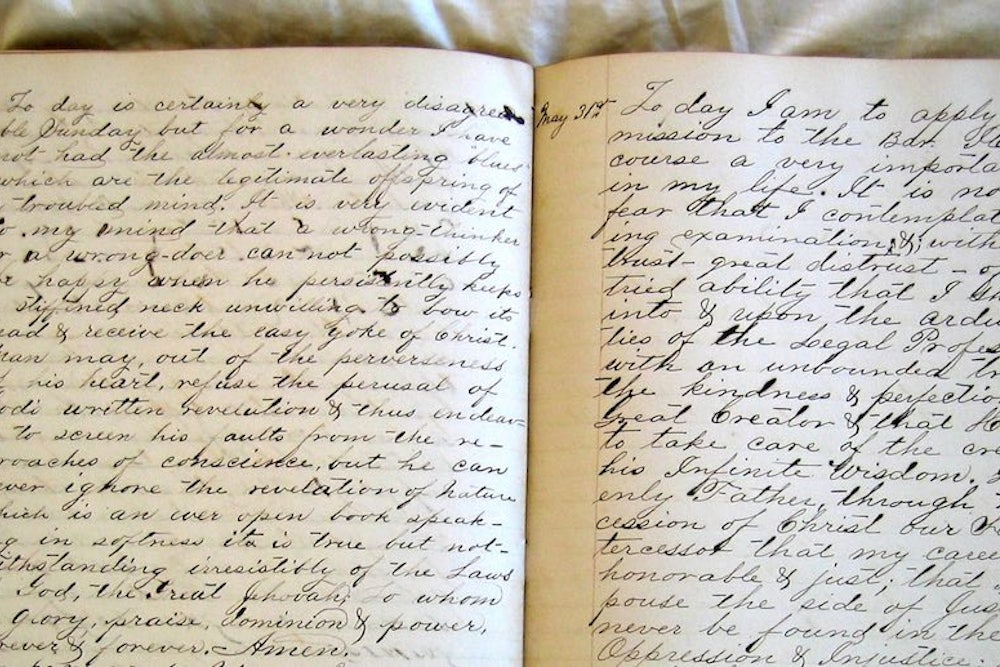

Around the time that I began to approach writing with any serious ambition, I fell prey to the misapprehension that the diary is an innately humiliating form—girly, maudlin, and unserious. How much better to be an essayist or a novelist than a diarist, I concluded, and how much better to keep a notebook than anything that might be associated with tiny padlocks and watermarked inspirational quotations. This slightly sexist distaste for the diary seemed widely shared, despite a long tradition of excellent literary diaries by both men and women—or at least it did until recently, when every third book recommended to me is either a woman’s diary, about a woman’s diary, or authored by a woman and somehow diaristic in its anatomy. Curious, I went ahead and did what no one wants to do with her own diaries: I reread.

It is occasionally fun to be flat wrong about something, and this current spate of women’s diaries overthrows any snootiness about the form so thoroughly and cheerfully that the subversion itself is entertaining. I’m thinking in particular of Heidi Julavits’s The Folded Clock, Sarah Manguso’s Ongoingness, The Argonauts by Maggie Nelson, Dept. of Speculation by Jenny Offill, Sheila Heti’s How Should a Person Be, and 8: unbelievable, all true by Amy Fusselman. (I could continue for a while.) These books aren’t being dismissed by critics or readers as fluff or exhibitionism, but celebrated, rightfully, as beautiful, genre-bending, and formally adventurous. These women are rewriting the diary into what it has always been in its best iterations: incisive, fearless, intimate, the ideal amalgam of intellectual and personal intrepidness.

There’s something conspicuously similar about these books and these authors. All are women in their late 30s and 40s; all are white, all are married, and (with the exception of Heti) all are mothers. Each woman seems to be writing, either explicitly or implicitly, in response to an anxiety about time. “From the beginning I knew the diary wasn’t working,” writes Manguso in Ongoingness, “but I couldn’t stop writing. I couldn’t think of any other way to avoid getting lost in time.” This is not a new worry. Diary-keeping as an attempt to hold on to what can’t be held is an old practice. “Remember what it was to be me—that is always the point,” wrote Joan Didion in “On Keeping a Notebook.”

The pleasure of this new group of books is that they confront the anxiety of time passing by forcing their readers into uneasy interactions with literary time. They unmoor you in the very element they contemplate. Ongoingness, for example,seems to accelerate: The book is fragmented, broken into increments of less than a page, some only a few sentences long, so the pages pass about three times faster than usual. Before you quite realize what has happened, it’s gone. Manguso's subject is ostensibly a colossal diary thousands of pages long that she’s kept her whole life, a loopy and obsessive text that she circles but never enters. Her true subject, though, isn’t the diary at all. It’s her struggle to exist and survive in time, to make peace with what she calls ‘ongoingness.’ (She takes the term from the writer George W.S. Trow, who wrote of his own life, “the ongoingness of it is, frankly, a real problem.”) “I tried to record each moment but time isn’t made of moments; it contains moments,” Manguso writes. Later, she admits: “To write a diary is to make a series of choices about what to omit, what to forget.”

Like Ongoingness, Jenny Offill’s Dept. of Speculation is fragmented; while it follows a loose chronology, it mostly proceeds from the associative logic of its narrator (who switches from first to third person about halfway through), which lends the book a floatiness that is by turns pleasurable and unsettling. It’s easy to share the narrator’s sympathy with a friend who, when marking up student fiction, sometimes “flips out and types the same thing over and over again: WHERE ARE WE IN TIME AND SPACE? WHERE ARE WE IN TIME AND SPACE?” Disorientation both plagues and thrills Offil’s unnamed narrator, and her reader.

Heidi Julavits, for her part, made The Folded Clock literally out of order. Each diary entry is dated only by the month and the day, and they’re jumbled so that the narrative jumps back and forth in time, disjunctures noticeable mostly because she’s in different places and different years from page to page. She’s in Maine, she’s in Rome; she’s at JFK Airport; she’s climbing a mountain in Europe. Each entry begins with a nod to the present (“Today I”) but many stray into the past or the future, or into alter-time, imagined time, scenes and events that Julavits pictures but has never lived. “How many more irksome moments like this will I have?” she thinks to herself as she rubs her wailing son’s back. “I must remember to do this when I am seventy. I must remember to close my eyes and imagine that I am me again, a tired mother trying to teach herself how to miss what is not gone.”

It’s curious that Julavits, Manguso, and all the other authors I’ve mentioned (again, with the exception of Heti) take motherhood as a primary subject. To become a mother, judging by these women’s accounts, is to enter into a particularly bizarre relationship with time. “In my experience nursing is waiting,” writes Manguso. “The mother becomes the background against which the baby lives, becomes time.” Nelson, in The Argonauts, writing about nursing, confesses: “I feel no urge to extricate myself from this bubble. But here’s the catch: I cannot hold my baby at the same time as I write.” Each lingers on the exquisite, punishing boredom of motherhood—Amy Fusselman, in 8, likens it to turning oneself into a robot—and yet the considerations themselves aren’t boring at all. This is writing about motherhood that has escaped the critical ghetto; the minds revealed are sly and strange and a little sexy.

Like many of the admiring readers of these books, I am not a mother, nor do I know what it’s like to have more than one decade of adulthood to remember. But I’m transfixed, as is more or less everyone I know. Why? In a way that seems related to, or at least magnified by, motherhood, Julavits, Manguso, and the rest conceive time as magical, non-linear, constructed, and a little rebellious—qualities most people instinctually sense but ignore in favor of the tidy and practical. “Time is inside us and outside us,” writes Amy Fusselman in 8. “It is the fantastic sea we move through, capable of the most astonishing bends and whorls. And, of course, like most things that are magical and wild and inside us, we have reduced it to something small and controllable outside us.”

The tendency Fusselman pinpoints appears as much in literary time—confining and organizing the ephemeral with linearity and structure, as is traditional—as it does in real life, where most people vibrate with an anxiety about over scheduling and smartwatches and device dependency so widespread it’s both functionally unnoticeable. But the question of busy-ness or the ill effects of being “plugged in” is less interesting than what minutes signify to us now.

The other day I overheard two teenage girls on the train: One explained to the other that she knew that her boyfriend was messing around because he used to text her back within ten minutes and now sometimes would wait hours. He’d claim to have left his phone at home. “I mean, please,” the girl said with a look of disdain, “Who leaves their phone at home any more? What is this, 2011?” Only later did she mention, as an afterthought, that he’d kissed another girl. This offended her less.

Time is maybe more excruciating now than it used to be because we are rarely allowed to be lost in it. The same machine that delivers us good and bad news tethers us to work, shows us pictures of our exes, buzzes at random with words from the people we most need to hear from or people we hoped never to hear from again. But before it does anything of those things this machine tells us the minute. Despite this regimentation, the minutes feel freakily elastic—there is no hour that feels longer than the hour spent waiting for a text message, and no bafflement like emerging from an internet k-hole to discover you’ve stayed up until 2AM looking at slideshows of zooborns.

Granted, time has always been weird and stressful. Proust’s narrator takes five pages to take three bites of cookie; Woolf’s moth takes a thousand words to shudder and die; one of Tobias Wolff’s most interesting short stories happens in the microsecond it takes for a bullet to pass through a man’s skull. In this spirit, the joy of the diary as written by Julavits, Manguso, and the rest is that they allow minutes (and days, and years) to be flexible—“fantastic and pliable,” as Fusselman writes. Which, of course, is how time actually feels, particularly in the moments that are most important. Sometimes, the sensation of tumbling through time is actually how we know a plain-looking moment is worth paying attention to. Near the end of The Folded Clock, Julavits describes a vertiginous outing, hunting for rocks with her father and her son:

I had spent many summer days as a kid trying to lose myself to fun on the islands. My father had spent many summer days… trying to lose himself to fun with me. We were at the mall. We were spinning tops. We were drilling downward. The disappearance of the invisible but present object—time—is how we fall back in people that we never, according to language at least, stopped loving.

Here, time is unleashed from being quantifiable or controllable—instead, it’s loopy and weird and huge, evasive and expansive. The pleasure of the passage (and the book it belongs to) hinges on turning the mundane into the magical, and granting permission to feel the bigness of the things we secretly know to be big. This permission is central to our delight in books that disorient us in ways that are somehow familiar, books that seem to shriek, in fear and jubilation: WHERE ARE WE IN TIME AND SPACE? What a relief to feel that it’s all right not to know.

An earlier version of this article misstated Tom Wolfe as the author of the short story "Bullet In The Brain", when in fact its author is Tobias Wolff. It has been updated to reflect the correction.