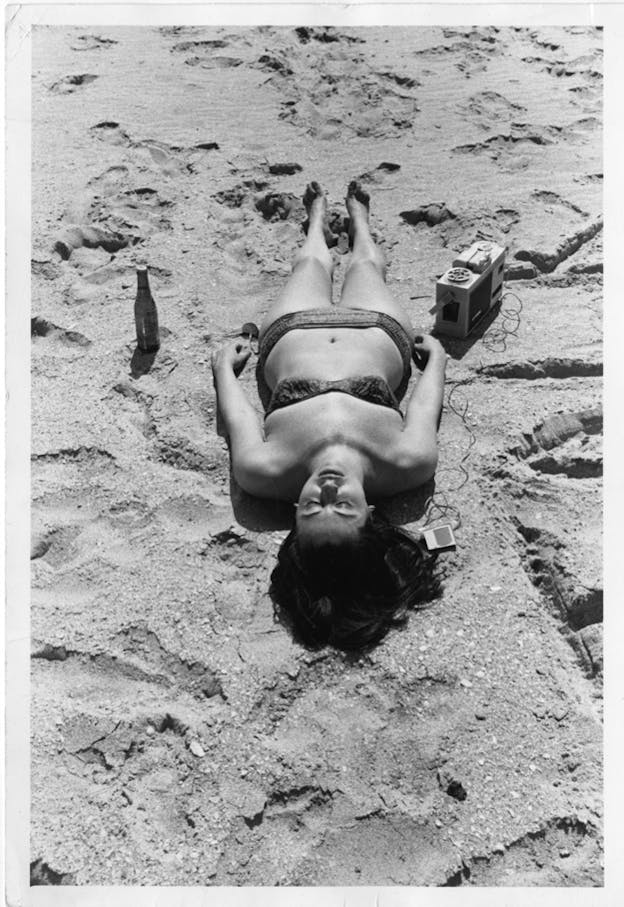

It’s the summer of 1965: the war in Vietnam rages; Bob Dylan goes electric; President Johnson signs the Voting Rights Act into law. The United States records its first spacewalk, the Supremes and the Beach Boys float to the top of the charts, and Watts is burning. Three friends from New York City, Emily, Marsha, and Vincent—the clever, expressive, and oft-intoxicated protagonists of Linda Rosenkrantz’s Talk—go to East Hampton to lie on the beach.

Talk is realism at its most literal, sourced from weeks of conversation between Rosenkrantz and her friends (captured by a portable, ever-rolling tape recorder). The friends are neurotic creatives: an actress, painter, and writer, respectively. (There is compelling evidence that Marsha is based on Rosenkrantz herself.) They flirt, gossip, divulge, and analyze; they eat and drink and fret. The book is solely dialogue—scriptlike in format, but stripped of blocking, emotional cues, and narrative description; action is implied by conversational digression. The characters’ banter is broken up into 28 short chapters (“Emily Relates Her Psychedelic Experience to Vincent”; “A Difficult Dinner”). All this makes for an unconventional novel that is equal parts experimental literature, confessional memoir, and art project.

Talk was first published in 1968; in the preface to the recent New York Review Books reissue, novelist Stephen Koch compares the novel to contemporary television, citing it as a predecessor to “Girls” and “Broad City,” with their shared emphasis on the “primacy of non-romantic peer relationships.” Nearly 50 years old, Talk also seems strangely well-suited to re-emerge into the contemporary literary landscape, with its recent interest in realism and interiority. Writers like Karl Ove Knausgaard, Heidi Julavits, and Sarah Manguso (among others) are documenting the small joys and existential crises of the quotidian. In distinct ways, they offer glimpses of lives that balance the demands of a creative practice with love, family, and other hungers.

But Talk also stands apart in its unabated exteriority. We never know what Emily, Marsha, or Vincent think; we are only privy to their public expressions. Every voiced desire or anxiety surely has a subterranean river of neurosis, but the reflexive introspection offered in memoir and fiction—the self-knowledge, self-loathing, self-appeasement—is inaccessible here. Ultimately, the novel is a two-tier performance: of first-person intimacy, of private and interior lives. Both a precursor and an original, Talk is an experiment in exposure that reveals the limits of realism.

Talk’s characters are well-educated, well-read, and culturally fluent, but, embracing the therapeutic thrum of the ’60s, they’re primarily interested in themselves. As active participants in psychoanalysis, the specter of the shrink lurks everywhere. They are eager to be examined; they jostle for attention. “You know you can’t say my analysis has stopped this summer,” Marsha says toward the end of their vacation. “It’s continuing on and on and on right under our noses.”

The three talk about drug trips and childhood trauma; they talk about their disappointments and heartbreaks. More often than not, they talk about sex. They are explicit and frank, delighted to entertain—but also unafraid to mix the dark and light. “He wanted it to hurt,” Marsha says. “He put golf balls in my mouth too but I kept spitting them out and they bounced all over the floor. It was very funny ... until all of a sudden I realized my God, my body is being stretched to death! So I passed out. I went totally unconscious.” When it comes to sex and drugs, Talk’s characters are gleefully curious, delighting in the newly created space to pursue pure pleasure.

Readers in 2015 won’t find sadomasochism revelatory, but Talk documents an era of liberation: Emily and Marsha entered womanhood as the country was starting to heave under the weight of cultural revolution, and they find themselves having to navigate the tricky promise of a liberated sexual and artistic life. In a chapter titled “Emily’s Problems Are Discussed on the Beach,” Vincent criticizes Emily, bluntly stating, “you expend all your creative energies on your love objects.” He reiterates this sentiment later on, in relation to his own potentialities: “An artist is already an accelerated, intensified human being and you cannot spend eight hours painting and then be a good, creative father.” The conflict between love and work—especially creative work—feels timeless. But here it’s inflected with the specifics of the era; choosing a creative life over a traditional one had only recently become a more viable option for many women.

For all their bravado, however, Emily and Marsha are still caught in the gulch carved between 1950s conservatism and 1960s promise. Born into a generation of women with more independence than any that came before, they have agency in their careers, pastimes, and, relevantly for this novel, in their mental health. Emily, who married and divorced in her early twenties, explains that she was almost institutionalized by her former husband while trying to break away from him; it is sobering to consider her fate had she been born a decade prior. They are feminists, to a point; they participate gladly in the sexual revolution, but their expectations for the future trend traditional.

Even in this landscape of increasing liberation, men hold sway. The women have male analysts and male doctors; they are haunted by their fathers and tormented by their lovers. At one point, they list their conquests with both swaggering pride and light self-disdain. “I hate my list, I’m bored to death with it,” Marsha complains. “It’s not that I’m bored,” says Emily, “it’s just that if that’s what my 30 years are all about, I could puke.” They disavow the men in their lives; they demand better. But still, they demand better men.

Deep into their unencumbered twenties, Emily, Marsha, and Vincent have neither romantic nor familial attachments; they just have each other. Their friendship is accepting, forgiving, and lovingly antagonistic. “I’m beginning to find everyone except you and Vinnie very dull,” Marsha says to Emily. “We’ve set up such a stimulating, total, free, hysterical, intimate, intense relationship that I find it impossible to relate to other people, they leave me completely cold.” Out of their parents’ homes but not (yet) with partners or children of their own, the three exist in a rare utopia: the self-made family. Like any utopia, of course, the fragility of this one is palpable; its disintegration seems inevitable. That men will be its downfall is practically foretold.

Marsha and Emily are acutely aware that they’re orbiting 30; they want more, or want to want more, even when it’s clear that the futures they’ll likely inhabit will still be fettered by misogyny and tradition. In a fit of tender vulnerability, Marsha recounts crossing wires with a former lover:

When he came in, he put his jacket on the back of the chair I later sat down in, and when he finally was leaving, he came over to me, and I thought he wanted to make up, be my boyfriend again, marry me, but he was just going for the jacket. It was the most humiliating moment of my life.

“Be my boyfriend again, marry me”: in the heartbreaking sincerity of this sentiment, Marsha betrays a quiet desire for her own future. On the brink of actualizing their adult lives, the rapturous trio runs the risk of flaring out. “Last night, Vinnie was really threatened with the loss of you,” Emily says to Marsha, after Marsha brings a love interest home, “which your eventual marriage will mean to him someday.” Despite the ardor and intensity of the trio’s friendship, the self-made family is only a stop-gap. Hopelessly in love with each other, the three anticipate nonetheless that the fulfillment friendship brings will ultimately prove inadequate.

Rosenkrantz has an eclectic bibliography: She is the co-author of Gone Hollywood, about the golden era of cinema, and has a short memoir, My Life as a List, composed of 207 numbered paragraphs about her childhood in the Bronx. In 2003, she published Telegram!, a collection of telegrams from historical figures. (She is also the author of a number of baby-naming books, and the founder of Nameberry.com, a baby-naming website.) Her work is concerned with human expression: speech, writing, the recounting of memory. It also scans as the output of someone curious about performativity: Hollywood stars, the limits of communications technology, the work of self-representation. My Life as a List seems inadvertently modern: It’s not hard to imagine something similar being published by BuzzFeed.

So it’s fitting that Talk, too, falls somewhere between obvious genres. It is not a raw transcript; it is a carefully tailored portrayal, complicated by the fact that its editor also lives in the text. But it’s not conventional fiction, either. The narrative arc of Talk is flat: The summer begins; the summer ends. There is no denouement. As in life, time simply passes. The characters leave as they entered: restless, anxious, hungry for a world that seems to be shifting. “We’re breaking psychic, social land so that people following us will be able to lead better lives,” Vincent tells Marsha and Emily, a statement buoyed by both self-importance and the currents of change. But Talk is a clear reminder that when it comes to hope—or freedom or feminism or equality—theory and practice move at unequal velocities.

Culture is cyclical. Social mores are stubborn. Talk has re-entered the literary frame after an almost 50-year respite, and its attendant conflicts of art, love, friendship, and connection are still fresh. Emily, Marsha, and Vincent desire more than their current lot, but as the novel unspools, it’s never clear, exactly, what the world can offer. They’re bored to death of men, but can’t imagine a future without them; they want creative lives, but have no model to live by. In the end, the existence of a balanced, liberated, and fulfilled existence may be its own performance. Driving home from a bar with Vincent, both of them contentedly drunk, Emily misquotes Lawrence Durrell: “We all lead lives of selected fictions.” Her selection couldn’t be more apt.