After this weekend, we know quite a bit more about how Hillary Clinton is going to campaign for president in 2016. What’s most startling is that she’s going to be running as a version of herself she’s been running from for more than two decades.

Perhaps the first clue came the day before her Saturday speech at the Four Freedoms Park on Roosevelt Island in New York City, when the Clinton campaign released a new video, entitled “Fighter.” A few seconds into the clip, a voice takes us back “before Secretary of State, before Senator, First Lady of the country” to when Hillary Clinton “was just a caring young bright creative student who cared about children and those left behind.”

The voice belongs to Marian Wright Edelman, a civil rights activist and public interest lawyer who worked with Martin Luther King on his Poor People’s Campaign and in that spirit founded the Washington Research Project and then the Children’s Defense Fund, a non-profit specializing in lifting children and their families out of poverty. Hillary Clinton’s first job out of law school was for Edelman; at the Children's Defense Fund she first worked as a staff attorney, then as a board member, and eventually as board chair. She has always credited Edelman with being her most important mentor and a close friend.

But after Hillary’s husband signed welfare reform in 1996, Edelman condemned it, issuing a statement that “President Clinton’s signature on this pernicious bill makes a mockery of his pledge not to hurt children.” And eight years ago, when her former protégée was first running for president, Edelman was asked by Democracy Now host Amy Goodman, “What are your thoughts about Hillary Rodham Clinton?” Edelman answered, damningly, “Hillary Clinton is an old friend, but they are not friends in politics.” Now, in 2016, it seems that Edelman is back on board. But in her callback to the time before the State Department, before the Senate, before her first tour in the White House, it’s telling that Edelman’s argument on behalf of a potential future president points straight toward Clinton's deeper past.

It’s not all that’s gutsy about Clinton’s latest roll-out, which she marked on Saturday with a lengthy, policy heavy speech. There’s also the fact that a mainstream Democrat is trying to become the first woman president by invoking Franklin Delano Roosevelt. Her speech, billed as her Campaign Kickoff, replaced recent Democratic simpering about Ronald Reagan and “reaching across the aisle” with jabs at trickle-down economics and a chilly invitation to cooperate with “willing partners;” that was refreshing. But even more surprising was hearing decades of centrist posturing give way to a citation of Roosevelt’s call for “Equality of opportunity … jobs for those who can work … Security for those who need it … The ending of special privilege for the few … The preservation of civil liberties for all … a wider and constantly rising standard of living.”

“That still sounds good to me!” bellowed Clinton, in her sturdy way.

And while Clinton’s delivery, like Clinton herself, was more dogged than flowery, even her language on Saturday showed leftward shifts toward sanity. Banished were the anodyne residents of “Main Street”; instead, Hillary spoke of “poor people” and “the wealthiest” and “income inequality,” mentioning the “middle class” only as a dying historical possibility in need of “a better deal.”

These are strong words, and certainly some new words, coming from a candidate with a long history of playing people-pleasing, power-appeasing, over-careful politics.

But this Hillary seems less afraid. In fact she seems downright determined to run straight into the blades of her own perceived weaknesses. On Saturday, she addressed her advancing age with a one-liner about how she “may not be the youngest candidate in this race, but … will be the youngest woman President in the history of the United States,” as well as with a feminizing crack about hair-dye and a senescent reference to the Beatles. In the campaign video released the day before the speech, she referred to her maddening tenacity and personal drive—the things that had half of her party hollering for her head in 2008—by laughing, “I think by now people know: I don’t quit.” She was also startlingly eager to remind people of that time she helped steer health care reform into a congressional iceberg during her husband’s administration, noting, “We worked really hard; we weren’t successful. I was really disappointed.”

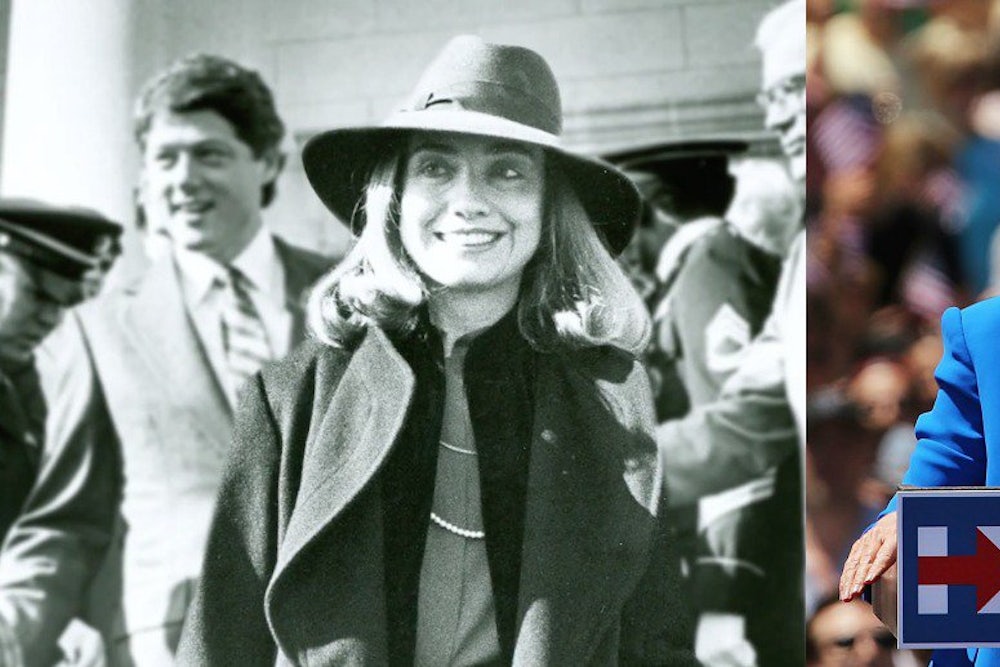

Most striking is Clinton’s willingness to showcase an older iteration of her professional persona: the one that was so unpalatable when she debuted it nationally, 25 years ago.

To undergird her new liberal policy positions on everything from immigration to incarceration to equal pay and paid family leave, Clinton is trotting out old biographical details—specifically the kinds of early professional commitments she’s spent years trying to make us forget. As a law student, she reminded the crowd, she investigated conditions faced by migrant workers and later became the head of the Legal Services Corporation, where she “defended the right of poor people to have a lawyer.” Clinton did not name the people who she was working for: Walter Mondale (on whose Senate subcommittee on migrant workers she served as a student) and Jimmy Carter (the president who appointed her to run Legal Services in 1978). But her prior associations with those two liberal politicians seem like exactly the kind of thing she’s now looking to advertise, after years of stowing them in a closet, somewhere under her unused cookie trays and Tammy Wynette LPs.

Clinton didn’t talk a lot on Saturday about criminal justice reform, but she nodded to it being on her docket with mentions of Legal Services and the legal aid clinic she ran in Fayetteville in the 1970s. Hillary’s critics have been dubious about Hillary and criminal justice reform, citing Bill Clinton’s role in creating a prison system in which so many Americans are now trapped. But Hillary Clinton’s early work was on the other side: as a law student, she monitored the Black Panther trials for civil rights violations; she interned for civil rights lawyer Bob Treuhaft; in Arkansas she worked as a public defender and as Politico recently reported, Hillary worked in the 1970s to get a mentally handicapped black man off of death row.

Few of these past efforts received much airtime during the years that Hillary‘s job was building support for her husband, who sold himself as a tough-on-crime former Arkansas Attorney General and famously returned to Arkansas during his first presidential campaign to oversee the execution of Ricky Ray Rector. Nor did they get much attention during her own early political career, when as a candidate for Senate in New York, she voiced her “unenthusiastic support” for the death penalty.

But that’s in large part because the young, driven, civil-liberties obsessed, coke-bottle-bespectacled Hillary Rodham Clinton was not welcomed with open arms. America did not much like this woman when she first came to us: ambitious and tough and liberal and feminist and interested in social progress and civil rights and reforming the world for women and children across classes.

She was called Billary, Hellary Rotten Clinton and a Feminazi; she was derided for being ugly, for being mannish, for being frigid, and for consulting with the ghost of Eleanor Roosevelt. Her hair was a problem, as was her desire to keep her maiden name. The Hillary happy meal was two fat thighs, two small breasts, and two left wings. There were voodoo dolls, nutcrackers. She was told to run like a man, to run like a woman, to cut her hair, chuck her glasses, be less divisive, be less conciliatory.

And so, in her quest to become a mainstream, powerful politician, she contorted; she bent and stretched to be more like what the people could stomach. These shifts were often contradictory, making them self-evidently inauthentic. She mostly stopped wearing glasses in public, she cut her hair, turned center, then right. She partnered with conservative coots on flag-burning bills and violent video games; she retreated from reproductive rights, calling abortion a “sad, even tragic choice”; she described herself as “adamantly against illegal immigrants” and voted for a terrible war.

Her willingness to shape-shift will always haunt her; she’ll pay for it in low estimations of her trustworthiness and moral timbre. Those costs are on her, and they are ones she may have calculated from the beginning. This is, after all, a woman who wrote her college thesis on the radical antipoverty organizer Saul Alinsky and who shared his belief that the key to change is the accrual of power. America didn’t like the woman who admired Saul Alinsky very much. So in an attempt to gain power, she changed.

But it’s also on us, and our longstanding lack of appetite for women who threaten or trouble us. Now that she’s recalibrating to the left, we’re facing a test: How much more—if at all—tolerant is this nation of difficult, disruptive liberal women, and how willing is Hillary to really commit to being one again? These answers will matter a lot to those American who liked original Hillary—and haven't much cared for the revised versions. Can she go back to being the women about whom the late Molly Ivins once joked, “What this country needs is a candidate half as good as his wife”—years before growing so dismayed by the candidate Hillary actually became that she refused to support her for president. And if Hillary does go back to being old Hillary: Can she possibly win?

It would be crazy to suggest that this is any less calculated than previous shifts: All of presidential politics, after all, is performance, and we should hope the players shift in response to the changing moods and needs of an electorate. But underneath are deep roots in this candidate’s past work.

Hillary—who wants automatic voter registration and extended early voting—understands the practical necessity of turning out a base, both as a self-interested presidential strategy and because as a student she registered black and Hispanic voters in Texas for George McGovern.

Hillary—who indicated on Saturday that she supports universal daycare and who is making paid family leave central to her campaign—learned late in her recent book tour that public opinion had shifted on these issues and has had to play catch-up since. But she also understands them because as a young woman, she cofounded the Arkansas Advocates for Children and Families, because she wrote a 1996 book called It Takes a Village, which did not offer policy prescription, but which does thematically foreground Clinton’s current framing of economic policies including paid family leave, universal daycare and Pre-K, higher minimum wages, equal pay, and ending mass incarceration as “family issues.”

Hillary—who spoke on Saturday about pay inequality, and how it applies especially to women of color—knows that she must draw those women of color to ballot boxes in 2016. But she also knows about gender inequity as a woman who went to Yale law after being told that Harvard didn’t need any more women, who as first lady of Arkansas published the Handbook on Legal Rights for Arkansas Women, who was the second female faculty member at the University of Arkansas School of Law and the first female partner at the Rose Law Firm, and who made the apparently revelatory observation that women’s rights are human rights.

Does the sudden relevance of her early work and life speak to a growing national tolerance for tricky, tough broads? Does it indicate that desperate economic times have created a need so intense that we’ll listen to populist messages emanating from any messenger?

Or has Clinton—with her muscular insistence on not quitting—simply worn us down and in doing so, made room for herself in our politics?

Whatever the mechanisms, it seems we’re about to get reacquainted with early Hillary. It’s a risky, brave gambit: betting on a controversial past with an eye toward a more equal future.

This piece has been updated.