One hot night in July 1972, I walked into my family’s kitchen to see my mother brandishing a broom at a skinny man who had his head stuck deep inside our refrigerator.

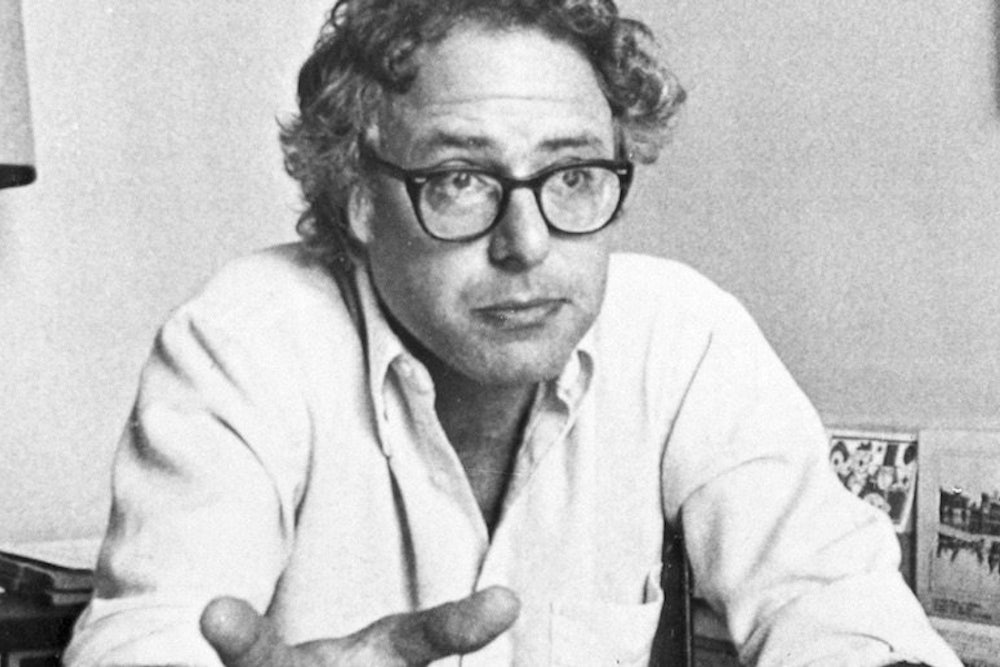

“You get out!” my mom yelled, hitting the man on his skinny ass. “Out, out!” Under her tan skin, my mother’s face was red with indignation. We didn’t have much in our fridge, but my mom would fiercely defend it. The man pulled his head out of the fridge, dropping the food on the shelf. His hair was curly; a cherub’s full-bodied curls framed his startled face. Chagrined, he loped off to the other apartment housed in my family’s converted two-room schoolhouse in Huntington, Vermont, the site of a late-night mock-up session for The Vermont Freeman, the alt-weekly my parents published. Years later, I’d find out that man was Bernie Sanders.

Standing on the waterfront park of Burlington, Vermont, on Tuesday, May 26, 2015, Sanders announced his candidacy for president. Shortly thereafter, Mother Jones published “How Bernie Sanders Learned to Be a Real Politician,” an article detailing Sanders’ decades-long shift from scruffy radical to hirsute politician. While the article delineates much of Sanders’ early history, including his time with the doomed Liberty Union party, his multiple failed political bids, and his hardscrabble hippie-adjacent life, the media fixated on one element: The “50 Shades” satiric erotica that Sanders wrote for the Freeman in October 1972.

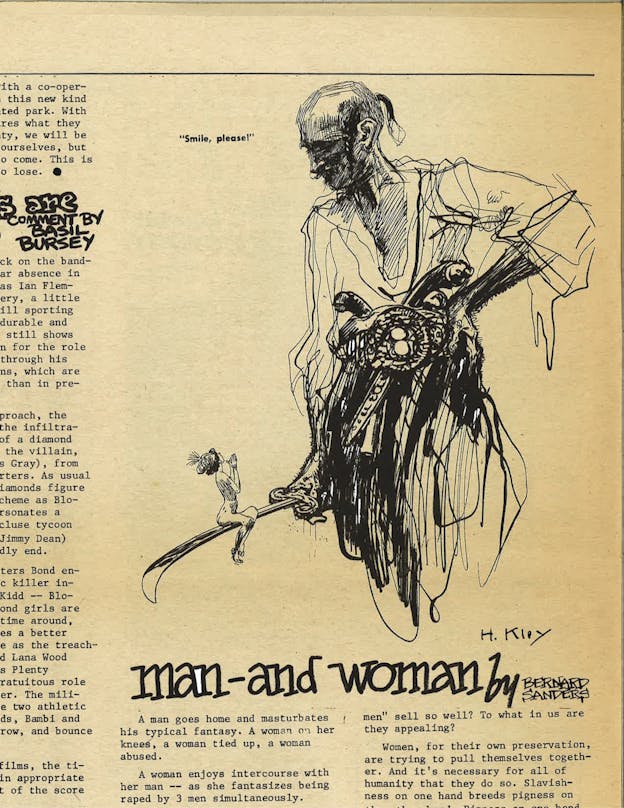

“A woman enjoys intercourse with her man,” goes the most quoted portion of the essay, “she fantasizes being raped by three men simultaneously.” Called “Man—and Woman,” the short piece originally appeared in the “China” issue of the Freeman. You’d likely imagine that an underground Vermont newspaper would have a hard time drumming up enough copy to fill a China issue—and you’d be right. The piece is bad, but it speaks to the gendered zeitgeist of the time, the ’70s confusion about who humans are when we can’t rely on the gender roles we grew up in with. It’s a confusion that lingers, suggesting that though his prose is execrable, Sanders is posing questions that were valid for the time, questions that the anger of Men’s Rights Activists and fourth-wave feminist divisions suggest are still relevant.

“It is very bad,” Frank Kochman, my father and co-publisher of the Vermont Freeman, said of Sanders’s 1972 piece. “But it has a wonderful graphic.”

“We were probably hard up for copy,” Jennifer Kochman, my mom, another co-publisher, added.

Distancing himself from the piece, even Sanders called it “bad writing,” but this was the text that the media fixated on; from NPR to the Washington Post and beyond, the media glommed onto Sanders’s semi-salacious prose. It certainly was the first time that The Vermont Freeman was featured on "Meet the Press." From 1971-1974, the Freeman, with a circulation of about 1,500 ranging across the state of Vermont and into New Hampshire, lived and breathed in our converted two-room schoolhouse. My dad calls the Freeman a “heavy duty, Hanoi Jane, anti-war, people’s revolution sort of thing—short of violent revolution; the Freeman never advocated actual revolution.”

The newspaper’s pages detailed the vicissitudes of the Vietnam War, local politics, labor strikes, generalized feminism, and whatever other food co-op–fed hobby-horses my parents and their friends were riding that particular week. Printed on newsprint with type laboriously cut and pasted by hand, illustrated by pictures my mom drew or found in clip-art, the Freeman looks like a forerunner to 'zines, and its copy often reads a lot like late-night posts to LiveJournal. Sometimes experienced journalists placed pieces too hot to publish anywhere else, but most of the paper had the feel of earnest kids doing everything they could to pretend to be real.

When I was a nine-year-old girl, I saw Sanders as just another one of the mop-haired, rangy hippies crowding my house. However, unlike all those other Freeman writers, Sanders was a radical who never left the political scene. While my parents left the Freeman to pursue other ventures—my dad became a lawyer and my mom did public relations for non-profits—Sanders didn’t abandon his politics. Instead, he made a career out of them, running unsuccessfully for Vermont governor and U.S. Senate multiple times as a Liberty Union candidate before being elected as an independent to the House of Representatives in 1991 and to the Senate in 2007. (Sanders has always caucused with the Democrats.)

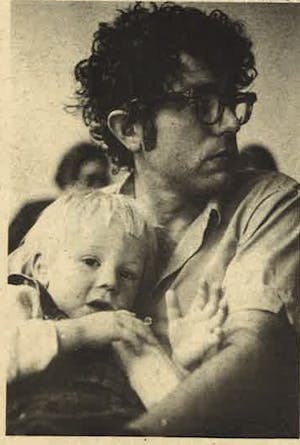

And it was as a candidate that Sanders first came into contact with the Freeman. In its identity as the liberal alternative to the then-conservative Burlington Free Press, the Freeman covered the nascent anti-war Liberty Union Party. Starting as early as October 1971, the Freeman covered the Liberty Union Party and its candidates, including a photo of a very young Senate hopeful Bernie Sanders with his son. Everyone looks so fluffy and soft, their children on their laps and nary a necktie to be seen.

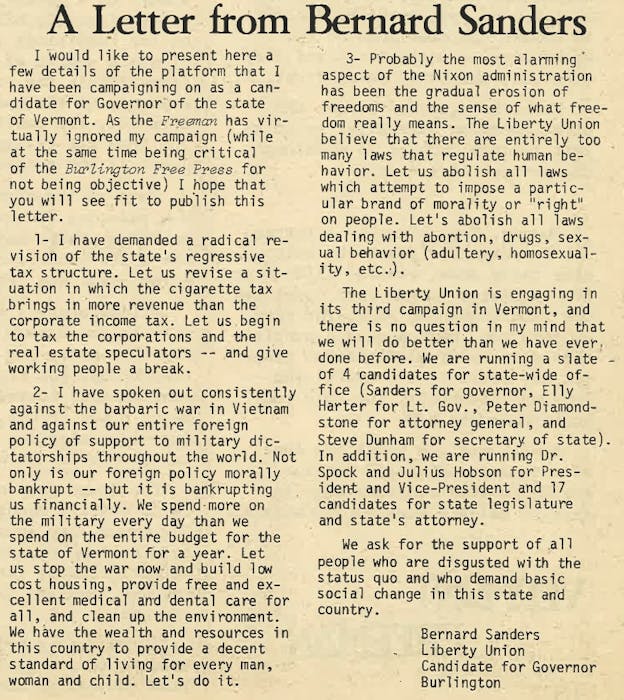

By the next year, Sanders had grown disillusioned with the coverage of the Freeman, and he penned a letter to the editor. Beginning with a churlish charge that the paper “virtually ignored” his campaign, Sanders continued to lay out a three-point campaign platform consisting of “a radical revision of the state’s regressive tax structure,” an end to the Vietnam War, and an amorphous call to “abolish all laws which attempt to impose a particular brand of morality.” Rather than an ethical argument, Sanders used finances as the basis for ending the Vietnam War and suggested that this money fund universal health care, low-cost housing, and environmental cleanup.

It’s a three-point policy that’s remarkably similar to Sanders’ current presidential platform, which consists of income and wealth inequality, getting big money out of politics, and working against climate change and for environmental causes.

As Sanders’ trademark truculent tone hasn’t changed, so too has his political position remained notably consistent. The 1972 senatorial candidate who somewhat hazily pledged to “abolish all laws dealing with abortion, drugs, sexual behavior” in his letter to the Freeman became a U.S. representative who voted against the Defense of Marriage Act, and just as he opposed the Vietnam War as a candidate, he voted against the use of force in Iraq in 1991, 2001, and 2003.

In that 1972 letter, Sanders opposed the “gradual erosion of freedoms and the sense of what freedom really means” in the Nixon administration—a loosey-goosey, hippie-dippy expression that, forty-plus years later, makes it hard to know what freedoms Sanders is referring to, exactly. However, the passage of time has solidified Sanders’ vague understanding of personal freedoms—or it has given him a well-defined foe, and he vociferously decried the Patriot Act and other “Orwellian surveillance,” as he called it. His voting record stands against big banking but usually with the NRA, necessary if you want to get elected in hunter-heavy Vermont.

“Bernie really is not much different now than he was then,” my dad says. “His ties and suits are way better—of course, he had no ties or suits, but he has been boringly consistent for 44 years.”

In 1981, my first election as a voter, I voted for Sanders’s first successful bid to be mayor of Burlington. It was the cool thing to do, and I did it to wear the button and prove my loyalty to the collective cool. Forty years later, it’s an uncanny thing to see this person I’ve known since childhood become a viable candidate for president. It’s like seeing my childhood validated, slapped on a campaign button, dissected by the press, and turned into a slogan.

My family moved out of that converted schoolhouse decades ago, but my mom loves telling the refrigerator story. She says she forgives him. “He was probably just hungry,” she says. “We all were.”