In Roberto Bolaño’s novel The Savage Detectives, an Impala’s worth of poets embarks on a road trip to track down their idol, the hopelessly obscure Cesárea Tinajero. The poets identify with something called “visceral realism,” a literary school Tinajero founded long ago. But Tinajero now resides somewhere off the grid of avant-garde history, her reputation kept afloat by word of mouth—with only a couple of mouths to speak of. Bolaño’s heroes haven’t even read Tinajero when they first set out on their quest; there’s nothing to read! They eventually turn up a single item: an unremarkable concrete poem Bolaño’s poets fail to find unremarkable.

Unlike Tinajero, Ida Perkins, the fictional poet in Jonathan Galassi’s debut novel Muse, possesses an oeuvre and a public. Moreover, she’s a fantastical index of one man’s sense of what matters—a well-placed man who has eyeballed recent literary history up close. Galassi, after all, is a translator, a former Paris Review editor, an accomplished poet, and, most conspicuously, the head of Farrar, Straus & Giroux, which stables John Ashbery, Elizabeth Bishop, August Kleinzahler, and many others. Muse focuses on Paul Dukach, an editor who works for a storied house not unlike FSG. (Purcell & Stern, we’re told, is the smallest of the big New York publishers.) Paul’s obsession is Perkins, the property of a rival house, Impetus (biggest of the small New York publishers). When the book begins, Paul has never met his idol, but will soon strike out for Venice, where she lives. He will come into possession of an unpublished Perkins manuscript and a revelation about a love affair.

An insider might be tempted to channel one’s inner sleuth and draw chalk-lines from Galassi’s creations to their corresponding, real-world counterparts. For a time, I figured Impetus was an analogue for something like James Laughlin’s New Directions, which trucks in experimental writing, has published Anne Carson and keeps Ezra Pound in print. But New Directions shows up in Galassi’s book, too. (Part of the fun of Muse is the way it generates friction: forcing real phenomena to rub shoulders with imaginary ones.) Galassi’s novel probably does conceal gossipy references to actual people: prickly talents he’s handled with garden gloves, bedhead reputations he’s groomed. And to be sure, the publishing world provides Galassi with satire-rich setting. (The novel’s rival publishers—one experimental, the other more commercial—parody the petty rivalries among literary types, who tend to specialize in hair-splitting.) But Galassi’s book deserves more than gotcha-grade guesswork.

What Muse is really about is fandom, about devoting one’s life to the life’s work of another: what all great editors come to do. In other words, what Galassi has created in Muse is a justification of his own life’s work. And what he’s created in Perkins is an improbable fantasy: the Ur-acquisition all editors dream of. “Ida was one of those rare poets who bridge the divide between aesthetic schools,” the novel assures us. She unifies Beats, formalists, Sylvia Plath, Adrienne Rich, and at least one Kennedy. She sees her lines turned into platinum by Carly Simon and Carole King, dabbles in Maoism, may have attended Woodstock, “was the only person ever to appear simultaneously on the covers of Rolling Stone, Tel Quel, and Interview.” Magazines like Time and “even the Reader’s Digest … were desperate to write about her.” She ranges so assuredly over twentieth-century culture, it’s a wonder Galassi doesn’t place her at a block party at the birth of hip hop, or in the background of the Zapruder footage, next to Forest Gump.

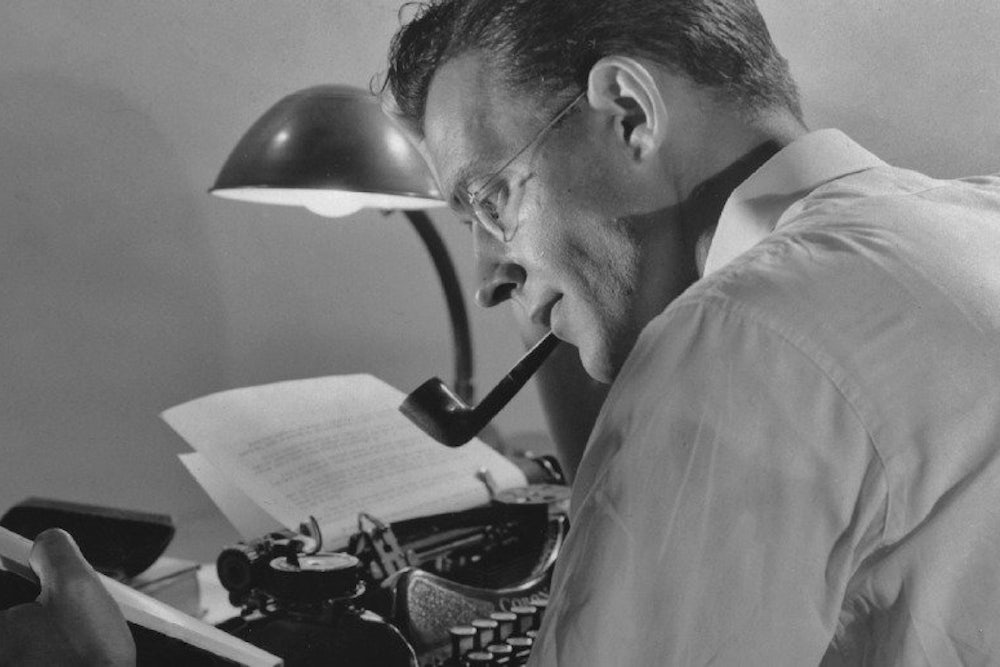

A poet who appears in Rolling Stone may be a fantasy, but it’s a charming one, and perhaps even a sly act of revenge on a world that has other, crasser plans for cover stories. Galassi worked at Random House in the 1980s, but was fired in 1986, because his books weren’t commercial enough. The underdog, however, was soon snapped up by FSG, where, ironically enough, he had a major commercial success with Scott Turow’s legal thriller, Presumed Innocent. But his tenure at FSG has also coincided with the publication of more prestigious works like Bolaño’s The Savage Detectives, Denis Johnson’s Tree of Smoke, and Marilynne Robinson’s Gilead. Among the many reasons to root for Muse is the gut feeling that its author would seem to know—would surely have to know, given his years in publishing—what makes for a good novel.

But if Ida seems newsreel-thin, so do most of Muse’s relentlessly quirky characters. There’s the crack team of editors who work at Purcell & Stern, “a raggle-taggle gatherum of talented misfits”—a kind, if unoriginal, character sketch. There’s the screwball literary agent, Roz Horowitz, “a canny old bird” who slings shit like, “Watch it, kiddo,” and “That and a nickel will buy you exactly nothing.” And there’s Paul’s boss, Homer, the sort of cartoon a creative writing student might draw up if tasked with picturing a publisher, whom Galassi feeds such lines as, “This is going to turn the literary world on its tail,” and, “I’m smacking my lips. Get yourself home today, baby.” But it’s not just what they say, but how they say it. “‘Don’t tell me you had to sleep with her,’ [Homer] guffawed,” when “said” would have done perfectly fine work. Perhaps these figures riff on real people, but they’re still so kaleidoscopically colorful they blow the spectrum and hurt the eyes.

It’s uncomfortable to remind a brilliant editor to show, not tell, especially when one has entertained dreams of being published by the editor’s press. But Galassi fails to trust his reader. “‘How did that novel by what’s her name, Fran Drescher, do?’” he has Homer say at one point, and then appends, in case you missed his point, “Homer was incorrigibly terrible with names.” Or consider this three-sentence exchange, between Paul and Ida, which condescends to the reader no less than three times, cudgeling her with theme:

“Well, I can see you haven’t learned much in your young years!” Ida shot back derisively.

“Forgive me, Ms. Perkins, but I hope you can appreciate how large you and Mr. Outerbridge loom in the imaginations of some of us,” he replied, perhaps a bit assertively.

“You’re not one of those despicable literary sleuths who thinks he can deduce every last little sordid biographical detail from a writer’s work, are you?” Ida asked, with ill-concealed suspicion.

Much of the first half of Muse reads like prologue: backstory to some other, better book in which characters reveal the finer points of their selves through dialogue and action. As it stands, Galassi’s novel is so top-heavy with history and exposition, its big revelation means little to the reader, who must take the narrator’s word that the characters are worth caring about. Moreover, the reader’s sense of a stock world populated by placards is reinforced, page after page, by clichés like “taken a shine,” “the way a cat plays with a mouse,” “larger than life,” “whetted the appetite,” “heartless world,” “pure gold,” “a thorn in the side,” “rat’s nest,” “out of the blue,” “wee hours,” “dream come true,” and “heart in his mouth,” among many, many others. One can’t help but wonder how a novel by a man who presides over one of publishing’s most prestigious houses seems to have largely escaped blue pencils.

What redeems Muse—or what can be salvaged from it—are the poems Galassi gifts to Ida Perkins. Novels about fictional poets, like The Savage Detectives and The Anthologist, tend to do the poets a favor and leave their poems off-page. But Galassi proves, as Nabokov did in Pale Fire, that exemplary poetry can be willed to order. Galassi isn’t Nabokov, but the poems he concocts are clean columns of free verse, flecked with internal rhyme and lovely turns:

How to go onwith thisheaviness allthis despairbeing kindreasonablepracticalorganized fairwhen what Iwant is to shutthe door openyour locket andfinger your hair

Fandom, Muse suggests, is its own act of creation. “Thanks to Ida … poetry not infrequently found itself at the heart of American culture and society,” we’re told, and if that’s wishful thinking, it’s also wonderful science fiction. But it’s not just that Muse posits a compelling counterfactual universe in which poetry fans might like to dwell. In fact, an imaginary editor’s extreme devotion to his idol has driven the real-world Galassi to an oddball achievement: the composition of a micro-oeuvre of fine poems that don’t quite belong to him. Ida Perkins certainly deserves inclusion in The Norton Anthology of Imaginary Poetry—an imaginary book, at present, but one that some great editor or other might be able to bring into being.