Before last week, the last time I’d been home to Cleveland, Ohio was in December of 2014. When I drove into town, I didn’t head to the East Side, where I grew up, and I postponed meeting up with my father downtown before we headed to Quicken Loans Arena for that night’s Cavaliers game. I didn’t even tell him where I was going. Instead I made a beeline for Cudell Commons on the West Side, where a pair of police cruiser tire tracks, three weeks old, were frozen into the park’s muddy grass. Steps in front of where they ended, a grey stone park table sat adorned with toys, ballcaps, a hula-hoop, and a sports jersey—a beautiful memorial for a dead child. A small black frame in the center of the table read, in stickered letters under the glass: “Tamir Rice / You Are Black Gold.”

A few days earlier that December, the Department of Justice demanded the city reform its abusive, unconstitutional policing tactics. Mayor Frank Jackson handed the investigation into Tamir Rice’s death over to the Cuyahoga County sheriff’s office just after New Year’s Day. It took more than five months for that sheriff, Clifford Pinkney, to provide a single public update on the investigation into the two officers involved. It is still ongoing. Not a day after the sheriff spoke did we learn that the slain 12-year-old’s body—preserved all this time in case investigators needed another look—had finally been cremated.

Last Saturday, six months to the day after Tamir’s death, I was in Cleveland again. I’d come home to give an awards ceremony speech a couple days earlier at my high school to a group of young black men and boys, grades 3 through 12. I talked about how they find themselves fighting a reputation they never earned, many of them regarded as “endangered species” and “at risk” through no fault of their own. Those descriptions, I told them, could lead them to believe in the scarcity of black excellence. “We are abundant and plentiful,” I said, gesturing at the stage of young black scholars behind me and to the audience in front of me. “Don’t let anyone tell you different.” I mentioned to them that I’d written about Tamir, but given how young some of the students were, I didn’t really tell them how much I fear for them.

I thought about them as I sat with my father watching television that Saturday morning, watching Judge John O’Donnell maundering about in legalese for a good half hour until he arrived at his sadly predictable conclusion: Michael Brelo, a Cleveland police officer who shot two unarmed black suspects in 2012, was “not guilty.”

Brelo, who fired 49 of the 137 bullets that killed Malissa Williams and Timothy Russell after a car chase, had been fully exonerated. It couldn’t be determined, the judge said, that of the 47 total wounds suffered by Williams and Russell, Brelo caused the fatal ones. Moreover, Brelo’s actions were ruled constitutional, though he jumped onto Russell’s car hood and fired 15 bullets Williams and Russell through the windshield. But, as the judge said, it couldn't be proven that Brelo fired the fatal shots. No actual killing, no manslaughter conviction.

Thus far, no one has going to prison for this excessive force. It appears no one will. The ruling set one hell of a precedent: You can riddle people with bullets as long as you have enough of your fellow police officers shooting. Along with Williams and Russell, accountability was lost in a hail of gunfire.

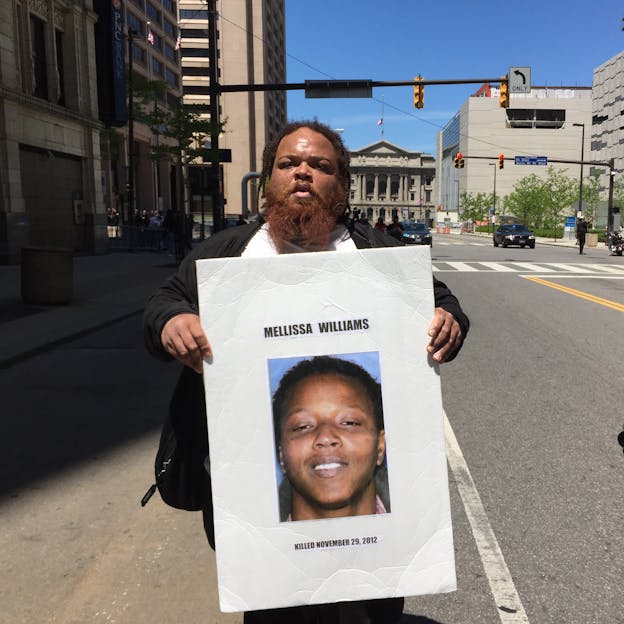

Afterward, there was an impromptu protest march. Alfredo Williams, Malissa’s brother, was part of it. He carried a sign that bore an image of her smiling over the date of her death, November 20, 2012. “This was real disrespectful,” he told me as we walked towards Public Square, the heart of downtown, together. “This man murdered her. He should’ve never got off on this. This was murder.” A disproportionate police presence kept pace with the few dozen marchers in front of us. I asked Williams about the DOJ inquiries. He urged them to look deeper into the Cleveland police department, reiterating that he doesn’t trust any city cop now. “None, whatsoever.”

LeBron James hasn’t shied away from black death in the past, at least in a symbolic fashion. Earlier this NBA season, the superstar Cavaliers forward wore an “I Can’t Breathe” t-shirt to honor Eric Garner’s family during New York City’s unrest last year; he previously encouraged his then-teammates on the Miami Heat to wear hoodies for a photo honoring one of their fallen fans, a 17-year-old boy named Trayvon Martin.

"For me, in any case, anything that goes on in our world or in our America, the only people that we should be worried about [are] the families that [have] lost loved ones,” said the Akron native on Saturday, shortly after the Brelo verdict. “You can't get them back. You can never get them back. We should worry about the families and how they're doing and things of that nature.”

Clevelanders are good at worrying. The city’s citizens are big on loyalty and short on hope. This is bred into us. We have to constantly reject the undeserved labels of laughingstock and “Mistake on the Lake” given to us by our municipal neighbors, all while experiencing the very real fragility that comes with, among many things, the collapse of industry and the incompetence of our local government. In recent years, a narrative of local renaissance of sorts has sprung up. When the Republican Party chose the traditionally liberal Cleveland for its 2016 party convention, the Plain Dealer editorial board went so far as to declare that the GOP had “validated the city’s relevance.” We can be a very insecure bunch. And this extends everywhere.

We are never less sure of ourselves, in my experience, than when it comes to sports—a source of national ridicule. That’s why I’m particularly glad that the Cavaliers, led by James, took it upon themselves to give locals a lift during a stressful week and clinch a spot in the NBA Finals last Tuesday night, in a four-game sweep of the Atlanta Hawks. The Finals, which begin Thursday night, are another rare chance to end the city’s 51-year championship drought in professional sports.

As a lifelong fan, I was glued to my television watching the confetti fall, large grin firmly in place. As happy as I was Tuesday night after Game 4, (and the Friday before, when I attended a watch party at the Q for Game 2), I couldn’t help but remember Tamir. At his memorial he was remembered as a basketball lover, someone who talked a big game while he played it. I don’t know if he was a Cavs fan, but I have to think he appreciated LeBron. Surely, he would have loved to see this.

A Cleveland team advancing this far typically gets the entire front page of the Plain Dealer. On Wednesday, the Cavs had to share with the mayor, a U.S. attorney, and the headline “Deal Seeks Sweeping Reforms.” The city of Cleveland had settled with the federal government on a second consent decree, another rebuke of its reprehensible pattern of policing. It calls for new training, new programs, and new accountability. Once the decree is approved, an independent monitor will be appointed to oversee the department. It will cost a lot of money. But it might be better.

This is a long way from working, and naturally, a town obsessed with its reputation is thinking about legacies. The local press pondered what Mayor Jackson will leave behind after this, his final term. (The announcement of the decree, however, came one week after a petition effort was launched to recall him.) The strong public-private partnerships needed to overhaul the department are, as of now, pledged, but still a pipe dream. Even if they coalesce, it may be a long time before Cleveland knows whether this Hail Mary worked. FRONTLINE senior reporter Sarah Childress wrote earlier this week that it takes an average of five years for police departments to fulfill their agreements with the Justice Department.

Until then, what of Alfredo Williams and the rest of the city’s majority-black population, those who are rightfully disillusioned with the police as they are forced to live through present injustice while they wait for promised changes? I hope the Cavaliers can provide a momentary boost for our moods as we live through a civic moment more embarrassing than any burning river. I wonder whether I gave false hope to the young men I addressed. But more than anything, I worry for my city, as I am wont to do.